Terminal demographics

About a week ago, I argued that the Great Inflation of the 1970s was largely a demographic phenomenon. That claim has provoked a lot of debate and rebuttal, in the comment sections of several posts here, and elsewhere in the blogosphere. See Kevin Erdman, Edward Lambert [1, 2, 3], Marcus Nunes [1, 2], Steve Roth [1,2], Mike Sax, Karl Smith [1, 2, 3], Evan Soltas, and Scott Sumner [1, 2], as well as a related post by Tyler Cowen. I love the first post by Karl Smith. My title would have been, “Arthur Burns, Genius.”

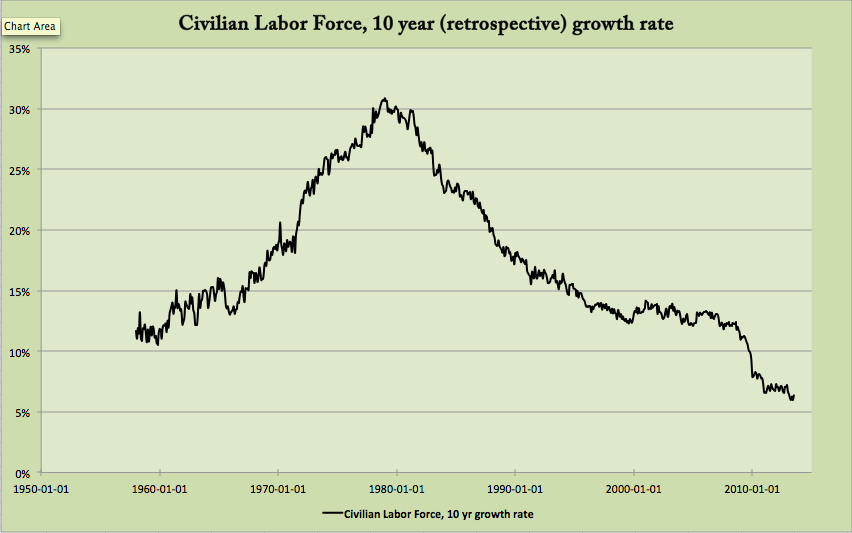

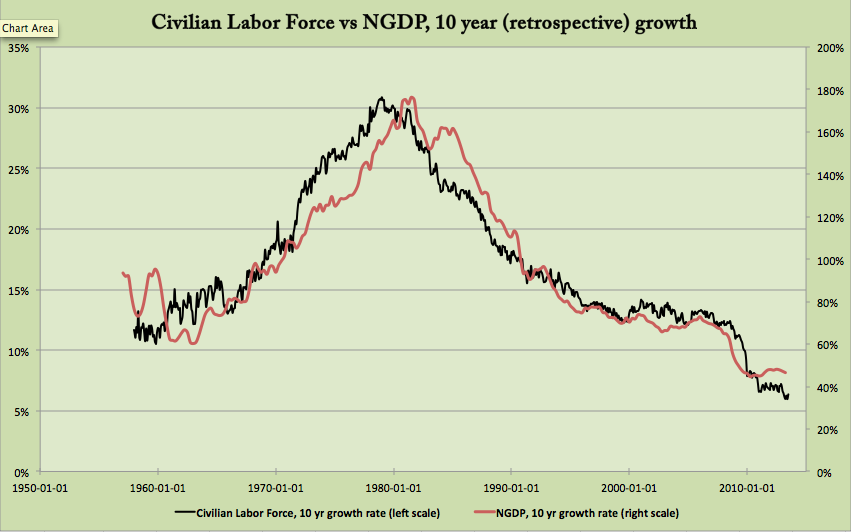

These will be my last words on the subject for a while, though of course they needn’t be yours. To summarize my view, I dispute the idea that the United States’ Great Inflation in the 1970s resulted from errors of monetary policy, errors that wise central bankers could have avoided at modest cost. During the 1970s, the simultaneous entry of baby boomers and women into the workforce meant the economy had to absorb workers at more than double the typical rate to avoid high levels of unemployment. This influx was effectively exogenous — it was not like a voluntary migration, provoked by the existence of opportunities. Absorption of these workers required a fall in real wages and some covert redistribution to new workers, which the Great Inflation enabled.

I don’t dispute that monetary contraction could have prevented the inflation of the 1970s. But under the demographic circumstances, the cost of monetary contraction in terms of unemployment and social stability would have been unacceptably high. As a practical matter, monetary policy was impotent, and would have been even if Paul Volcker had sat in Arthur Burns’ chair a decade earlier. I am perfectly fine with Evan Soltas’ diplomatic rephrasing of my position, that perhaps inflation remained a monetary phenomenon, but that the 1970s generated a “worse trade-off [for policymakers that] was not a monetary phenomenon”. I don’t claim that monetary policy was “optimal” during the period. Policy is never optimal, and in an infinite space of counterfactuals, I don’t doubt that there were better paths. But I do think it is foolish to believe that the policy decisions of the early 1980s would have had the same success if attempted during the 1970s. Monetary contraction was tried, twice, and abandoned, twice, in the late 60s and early 70s. There was and is little reason to believe that just holding firm would have successfully disinflated at tolerable cost in terms of employment and social peace. I don’t claim that demographics was the only factor that rendered disinflation difficult. With Arthur Burns (ht Mark Sadowski) and Karl Smith, I think union power may have played a role. It also mattered, again with Smith, that “unemployment was poisonous to the social fabric and the social fabric was already strained, most notably by race relations”. Monetary contraction succeeded — third time’s the charm! — when the demographic onslaught was subsiding, when Reagan cowed the unions, when the country was at relative peace. It might not have been practical otherwise.

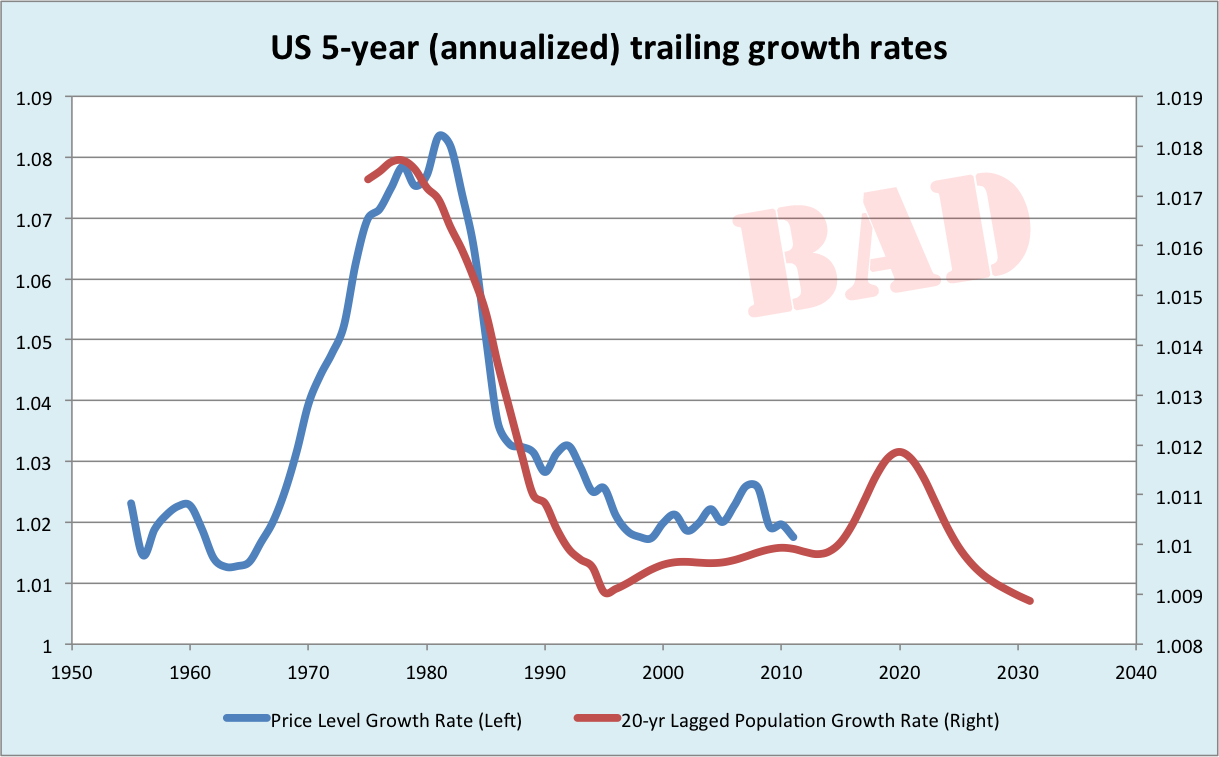

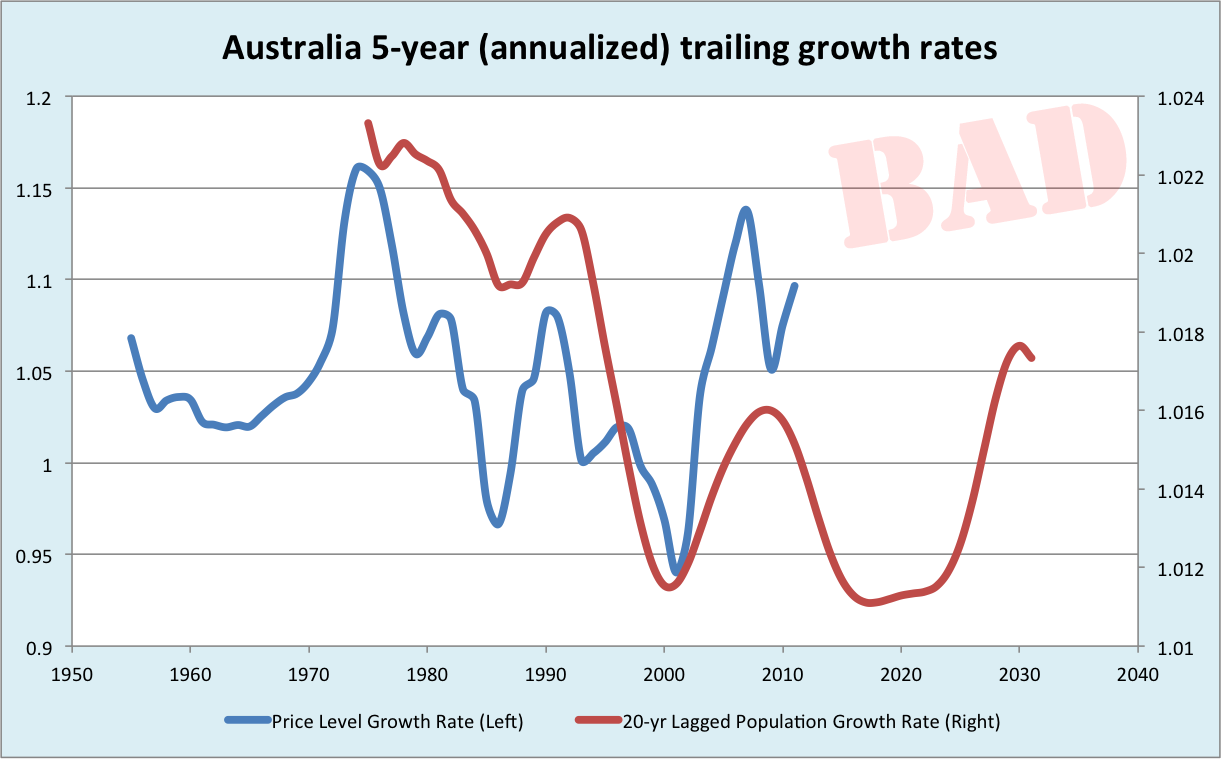

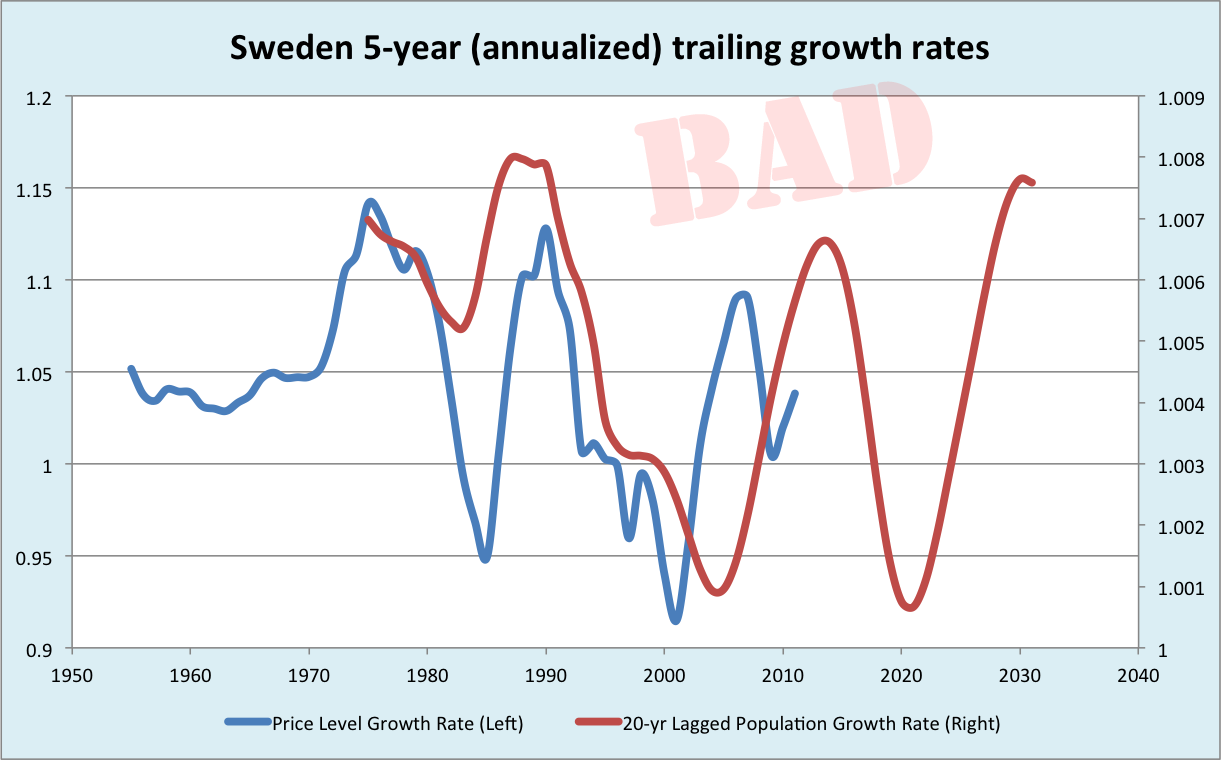

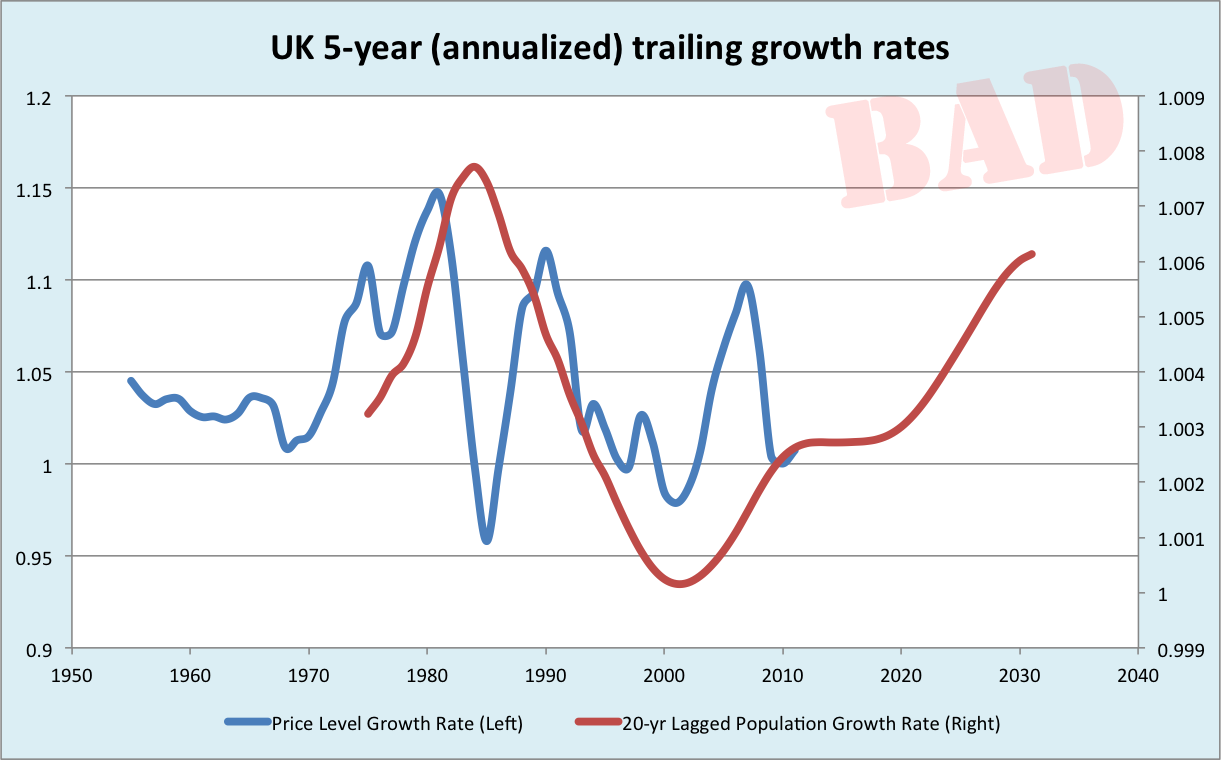

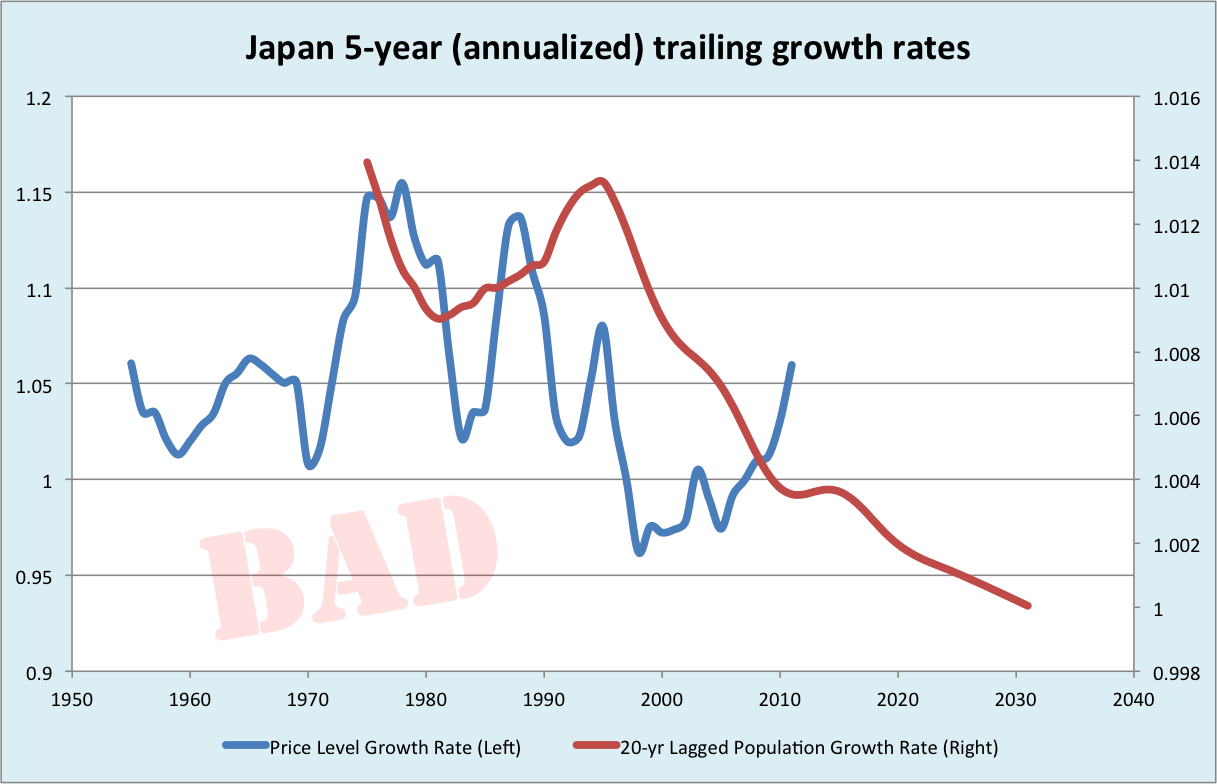

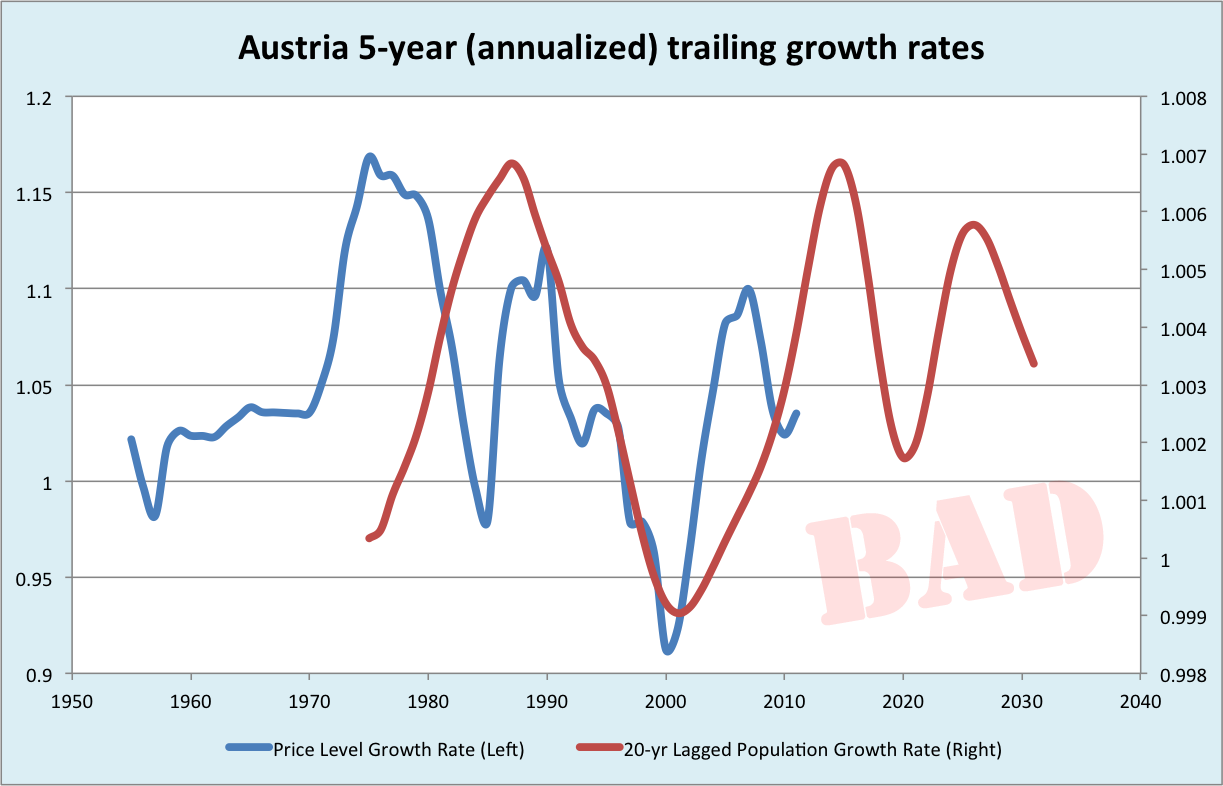

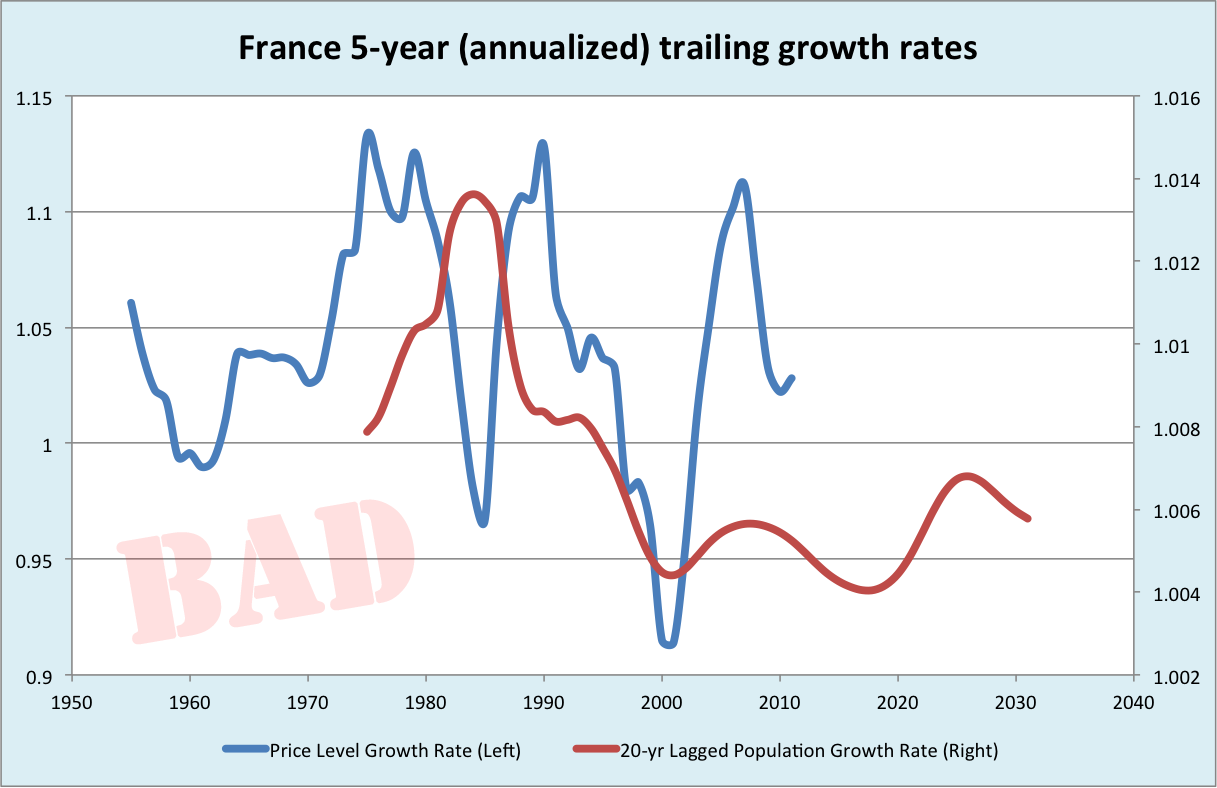

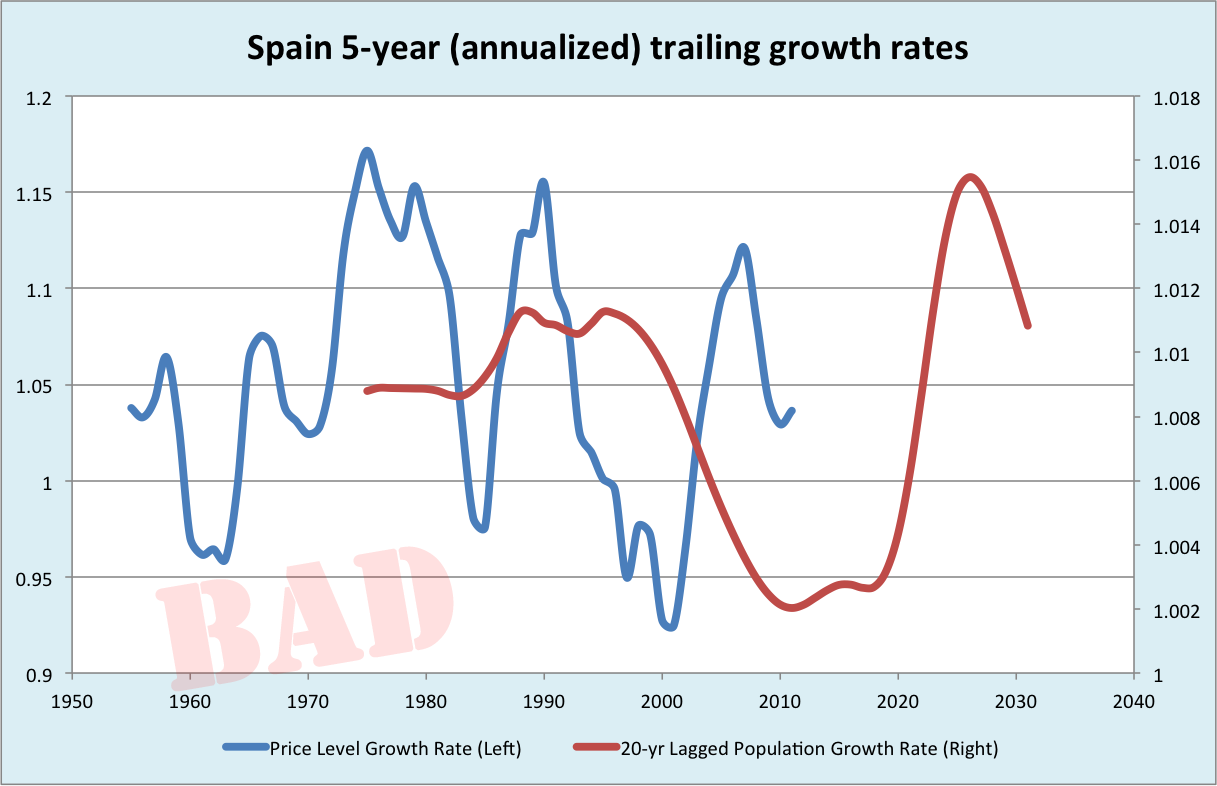

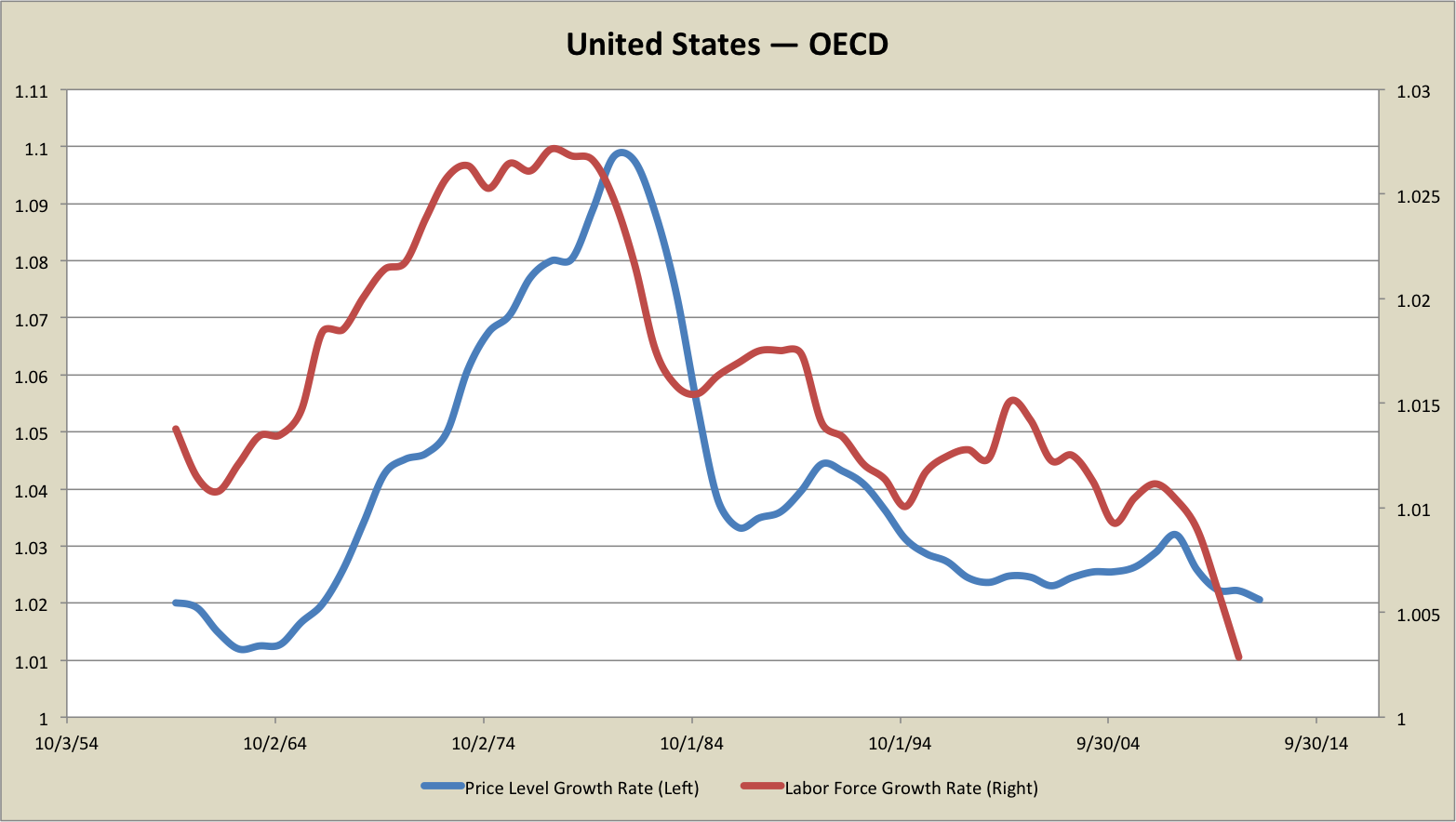

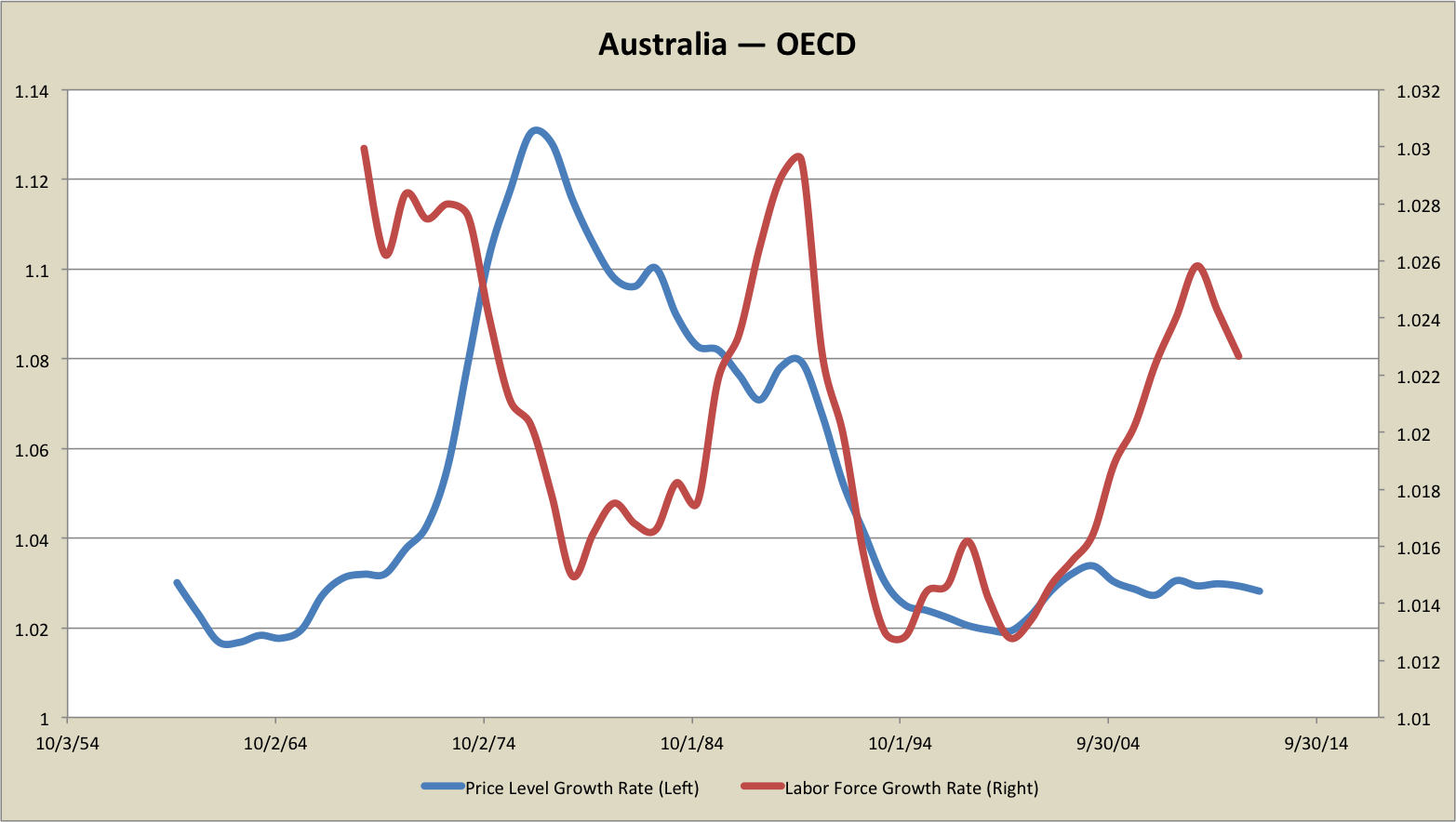

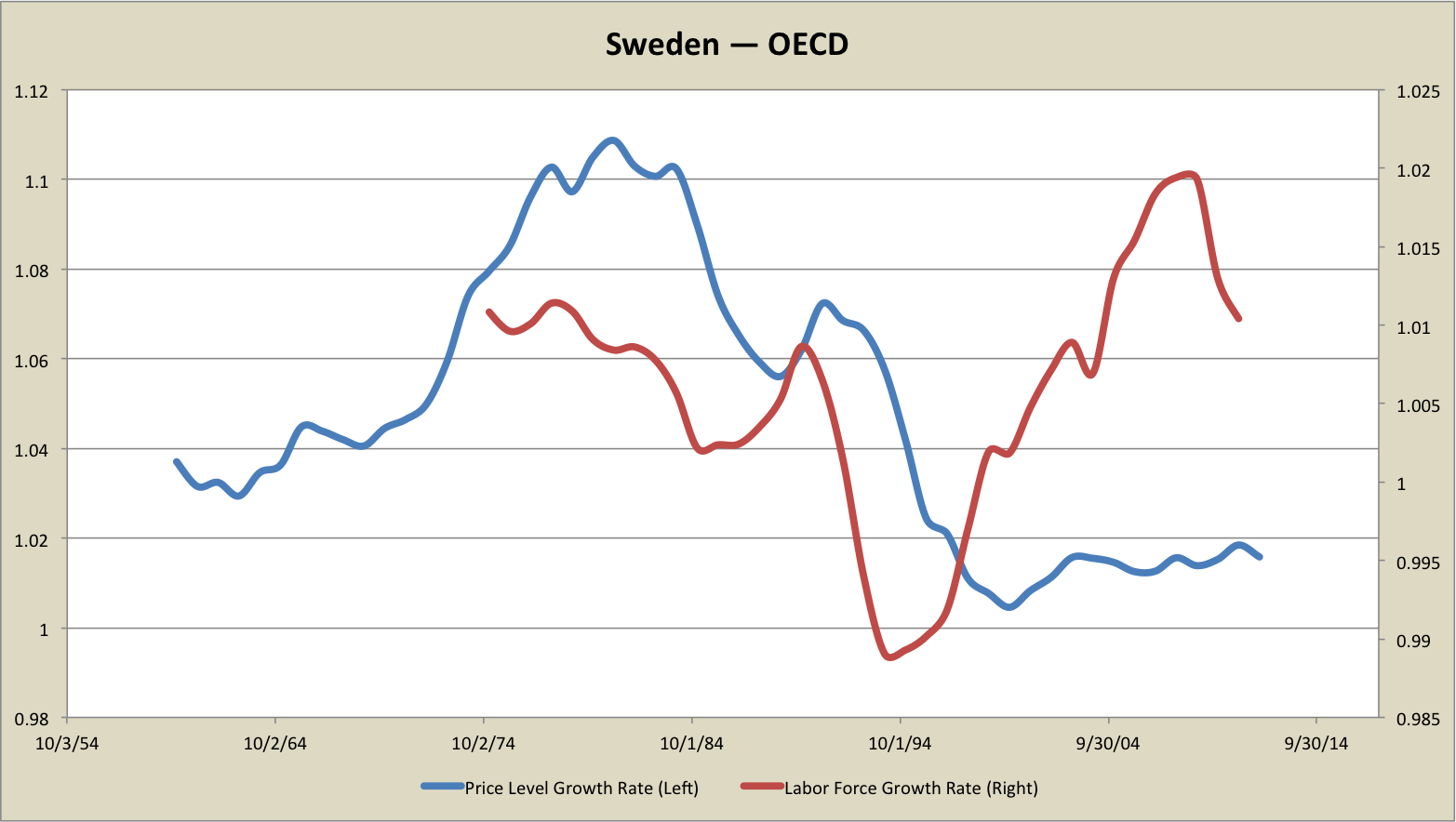

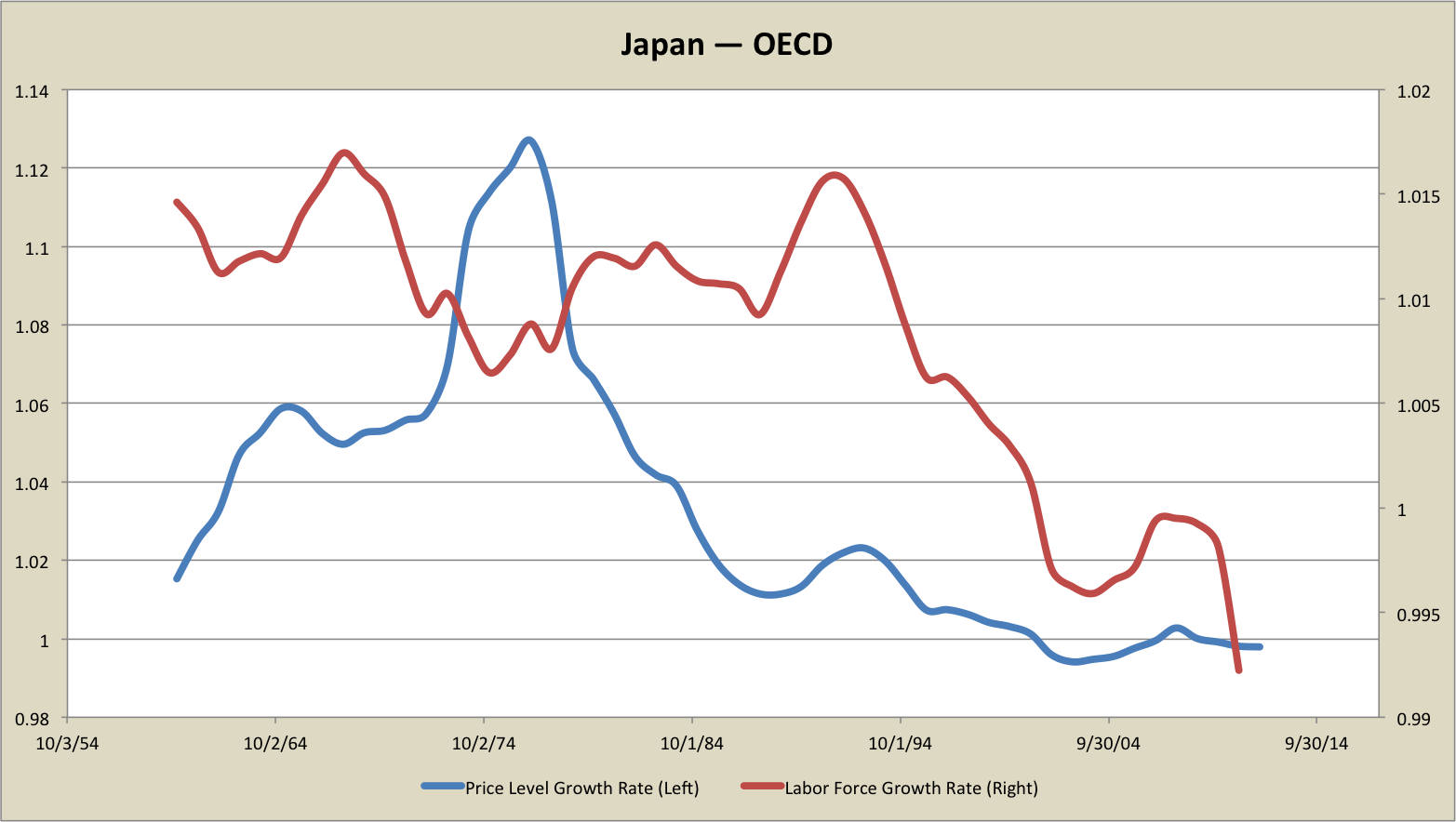

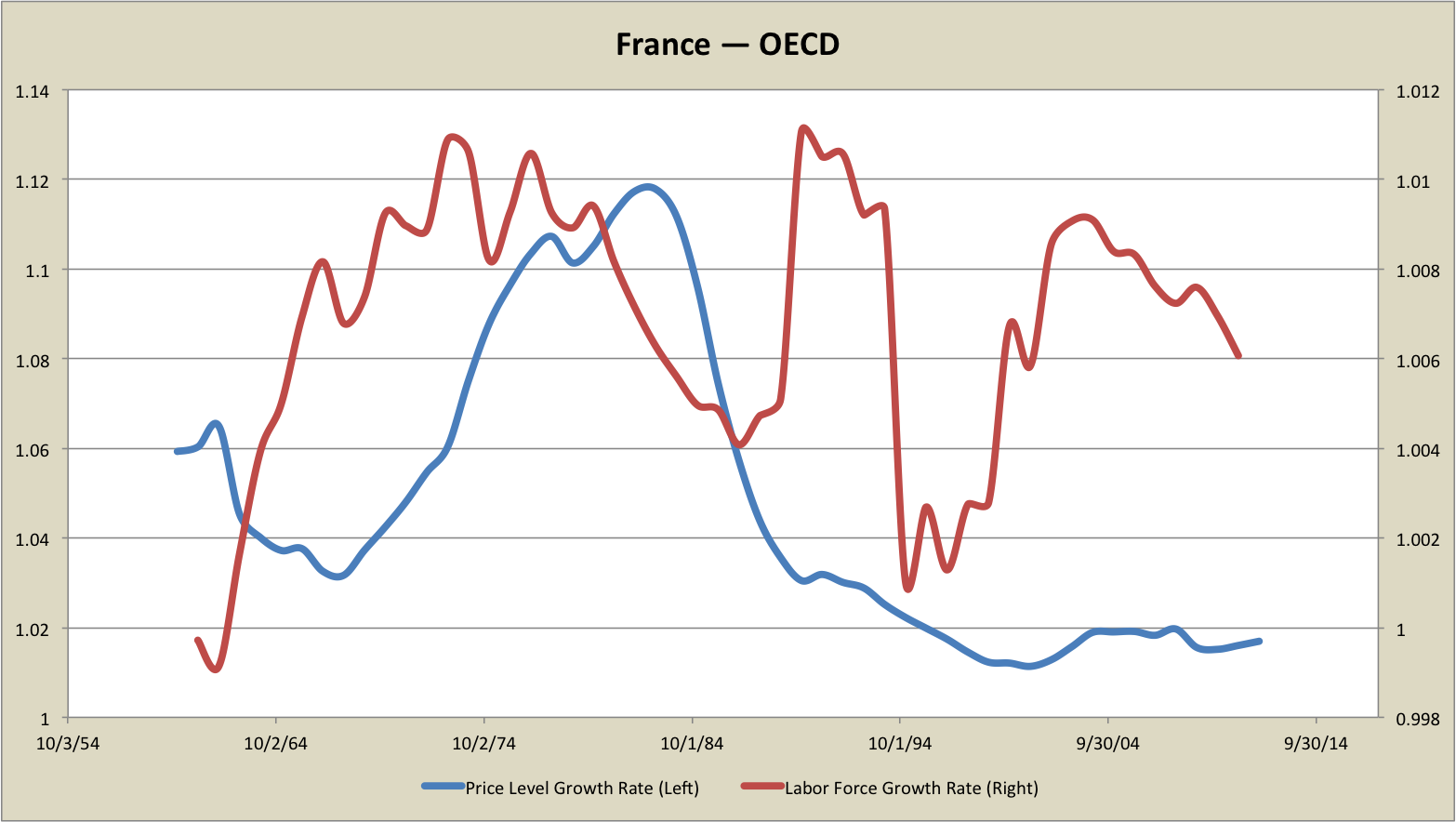

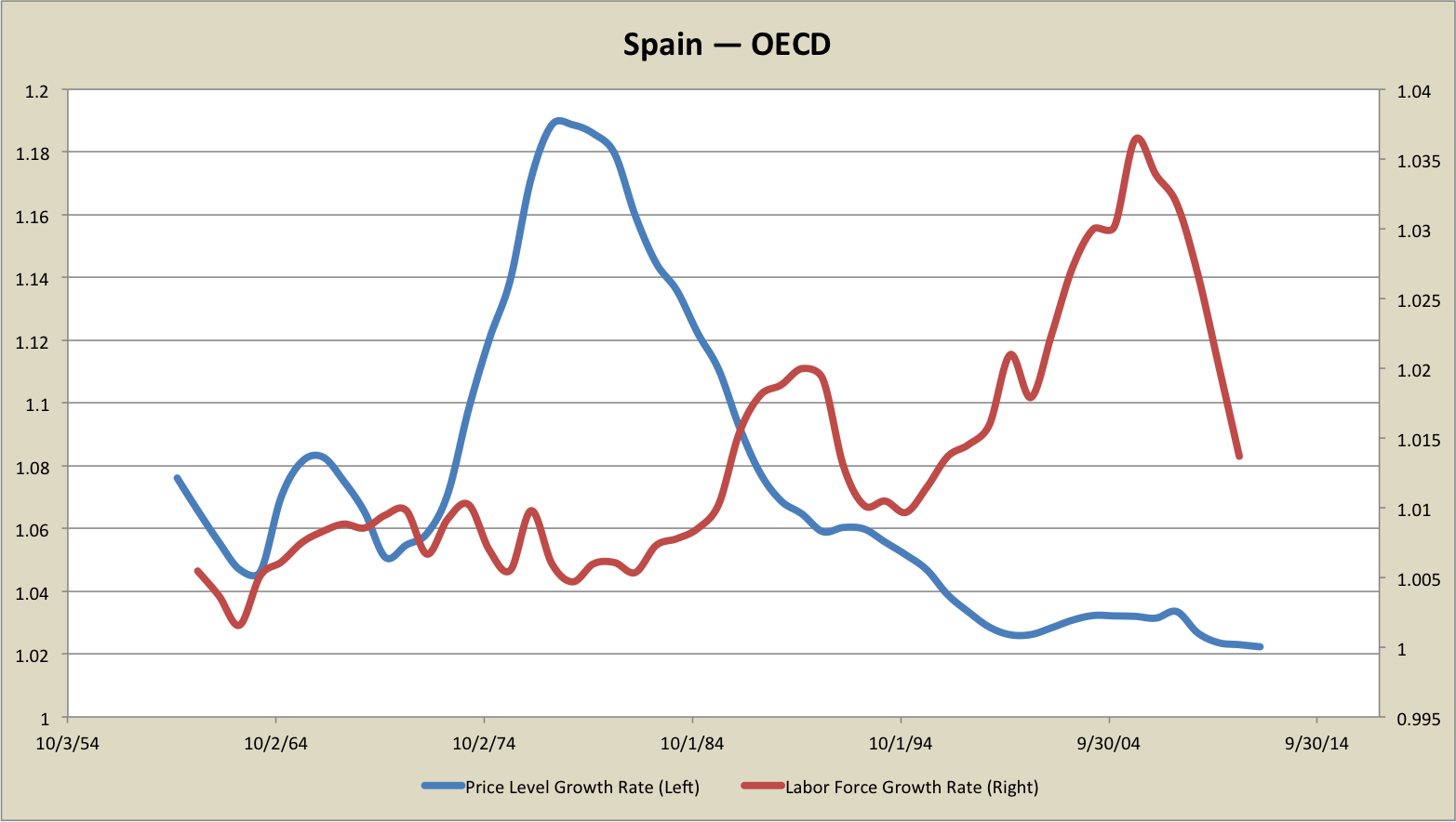

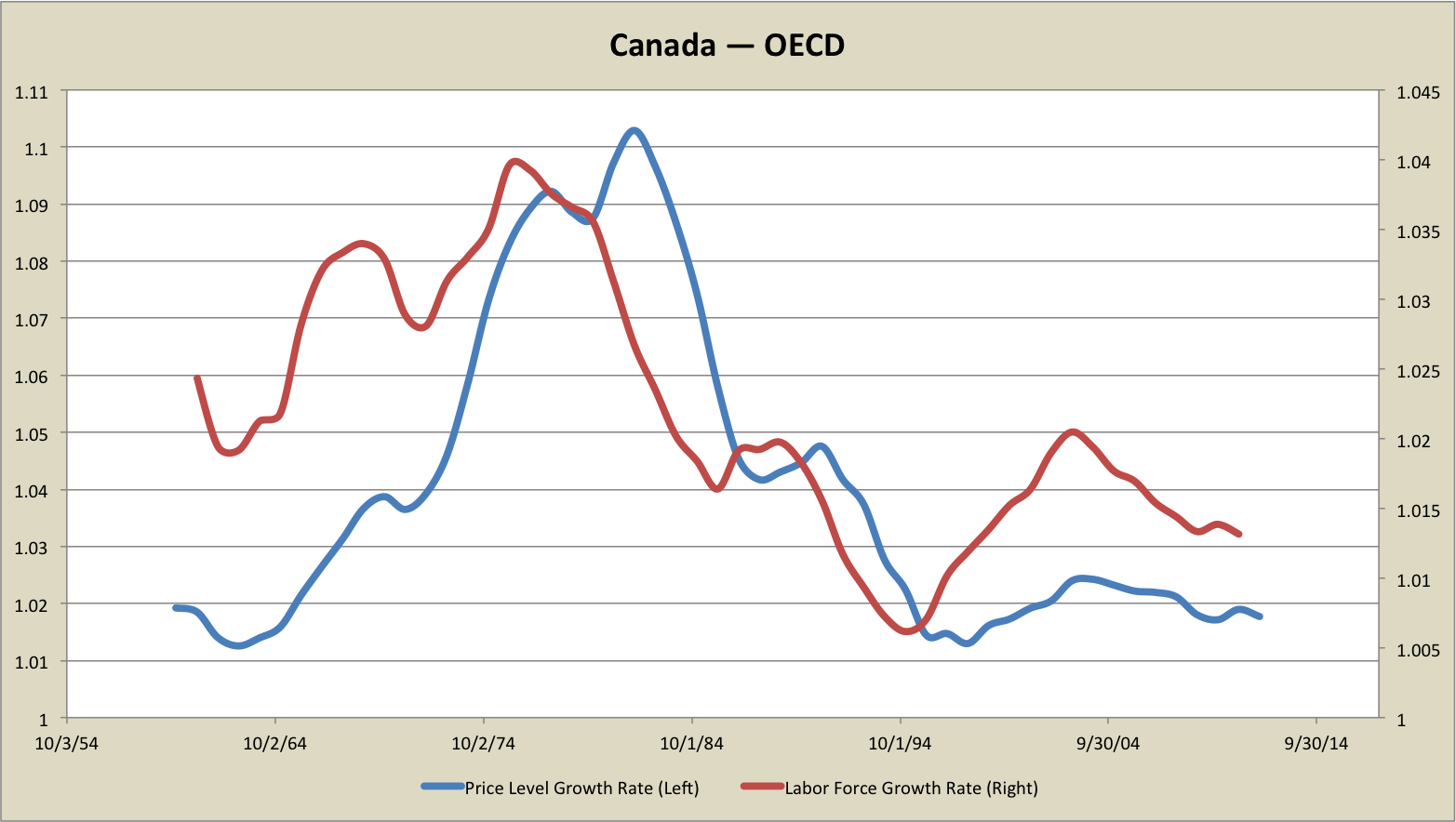

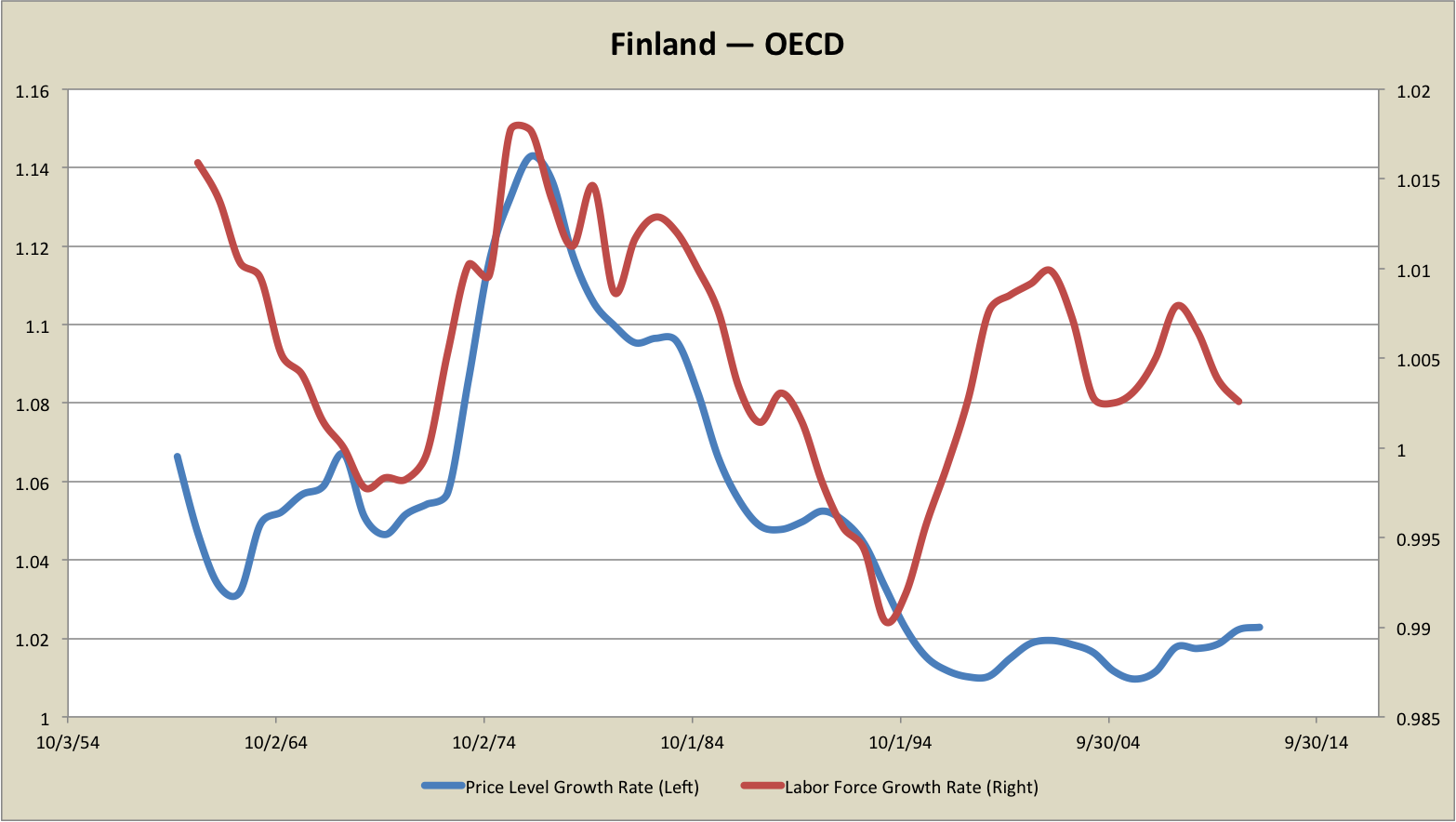

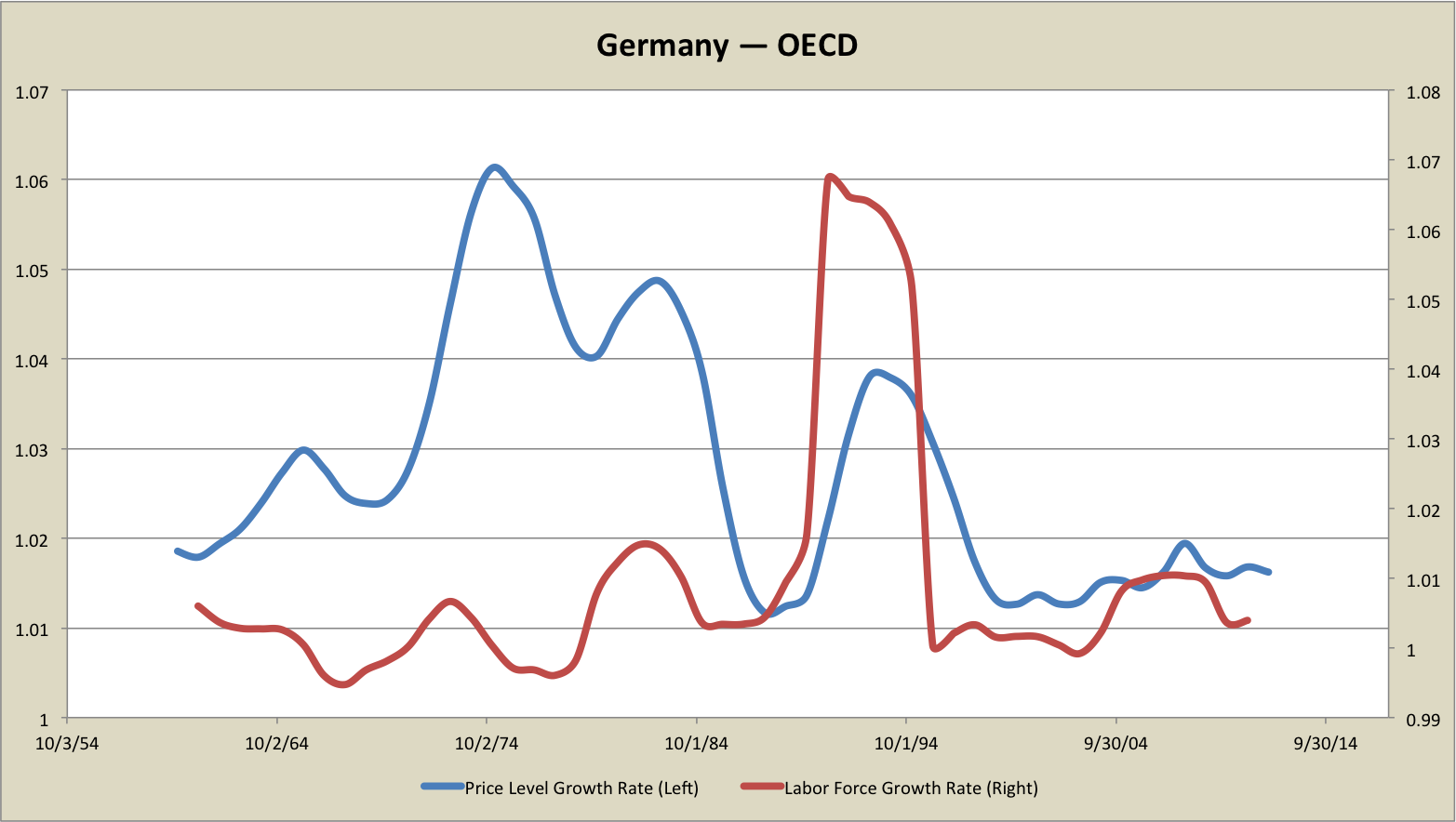

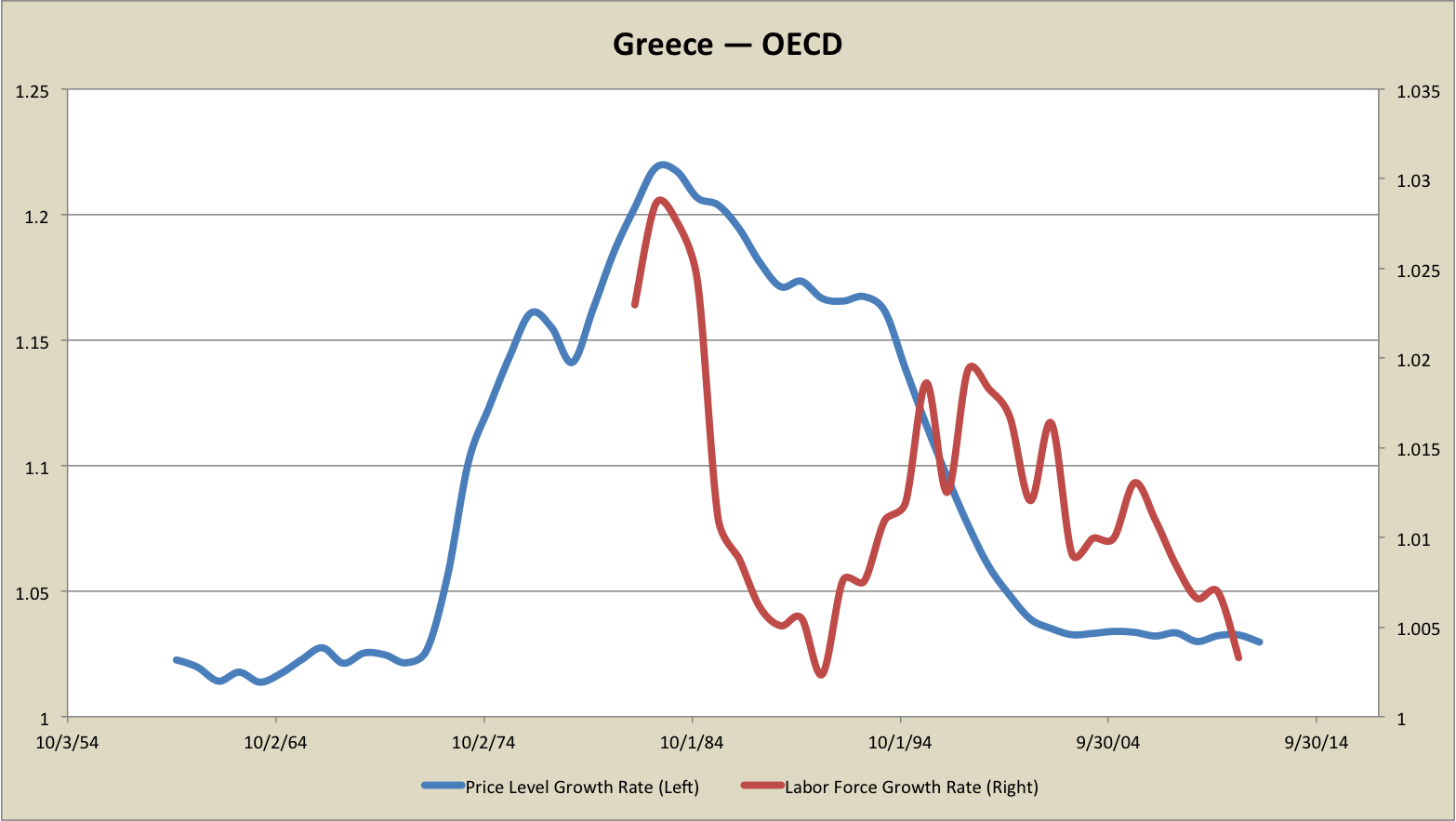

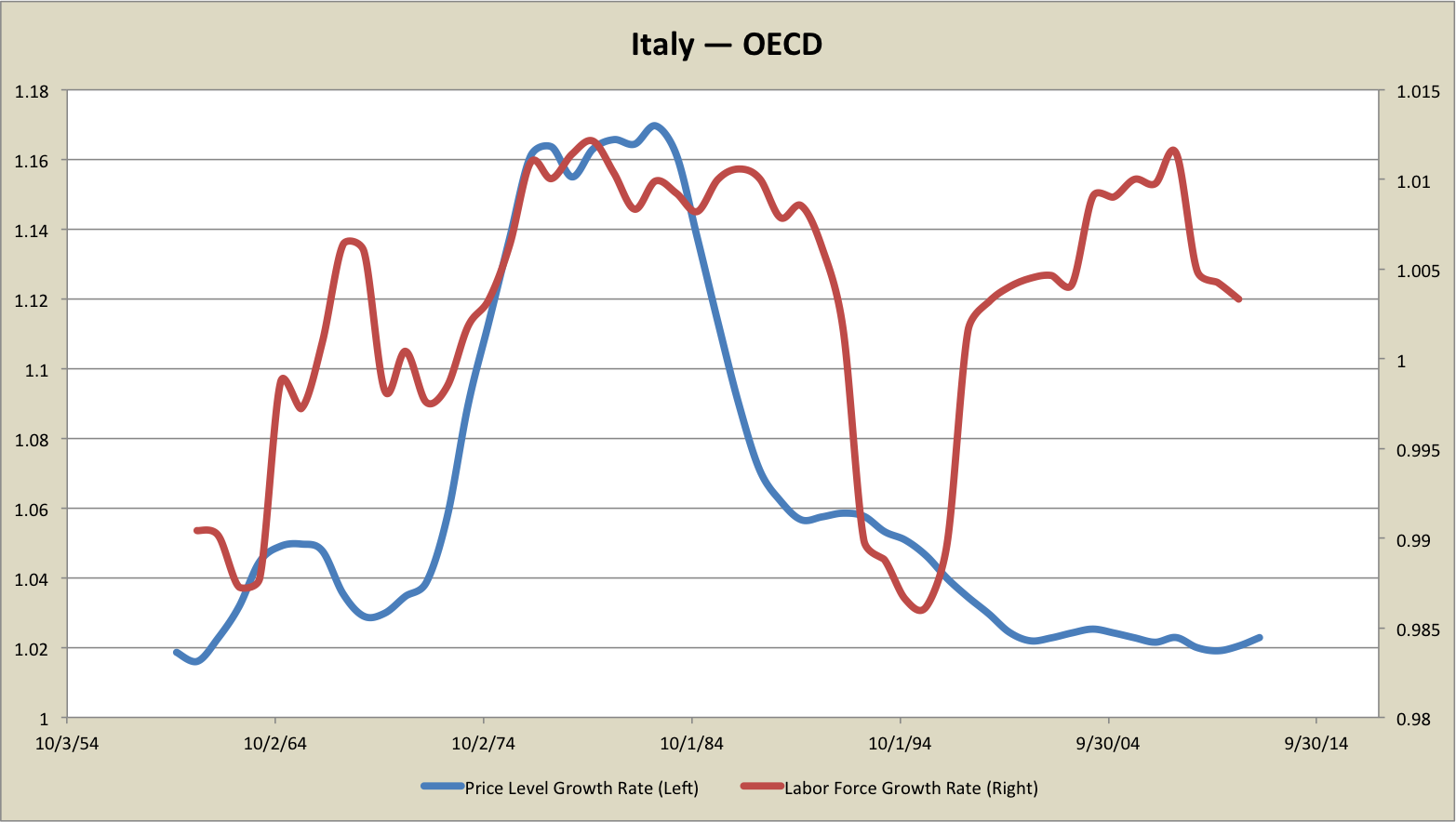

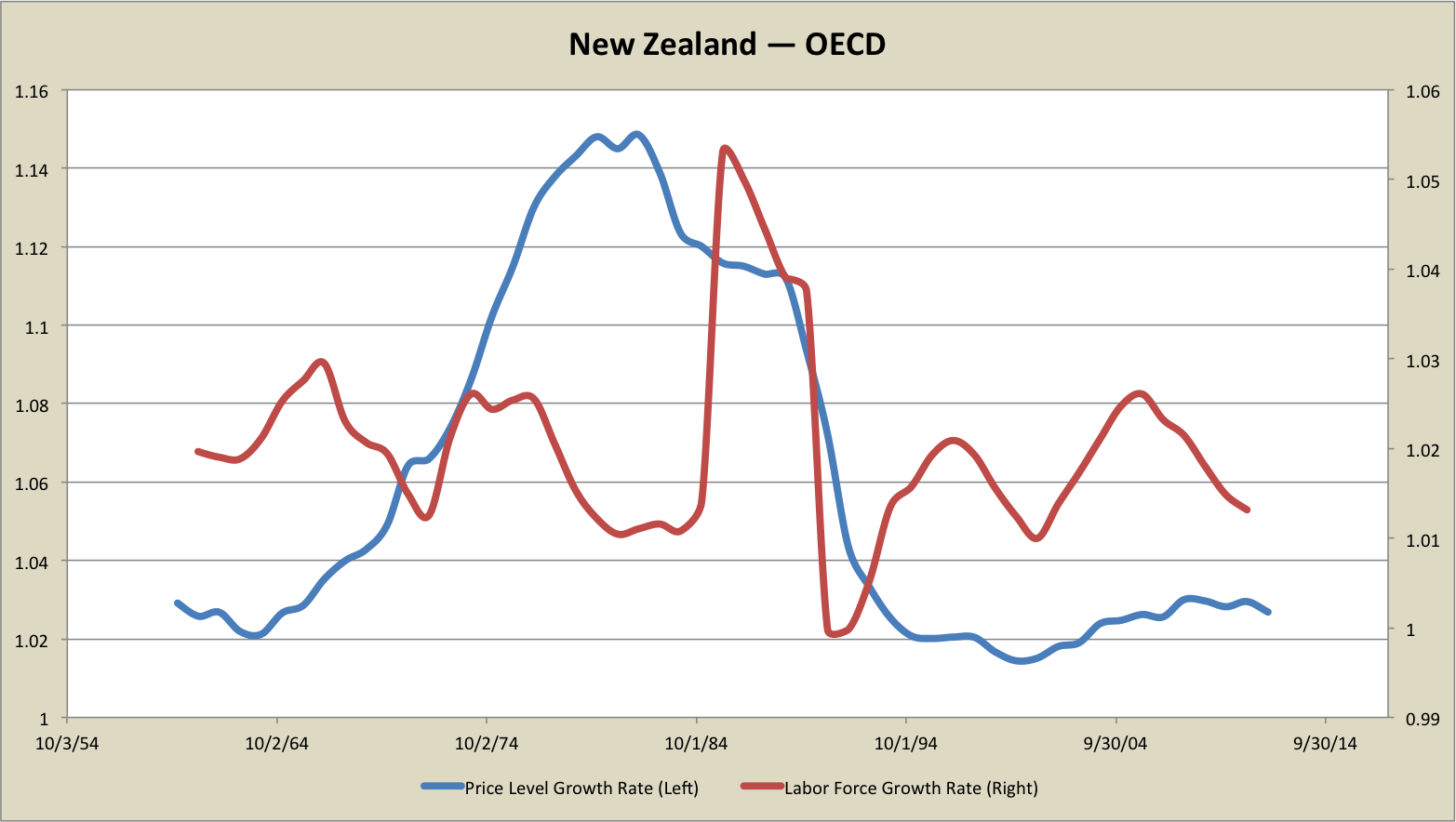

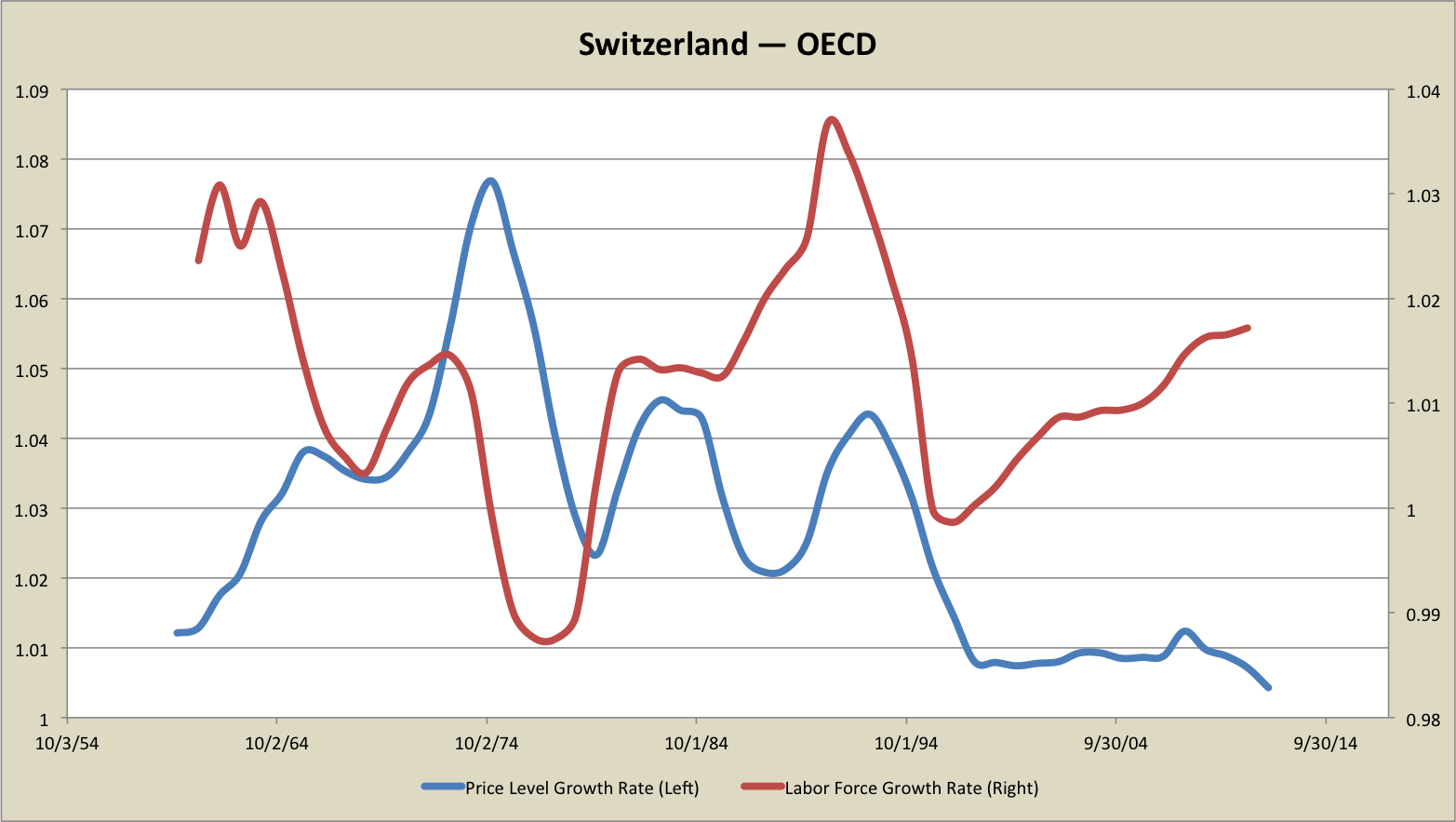

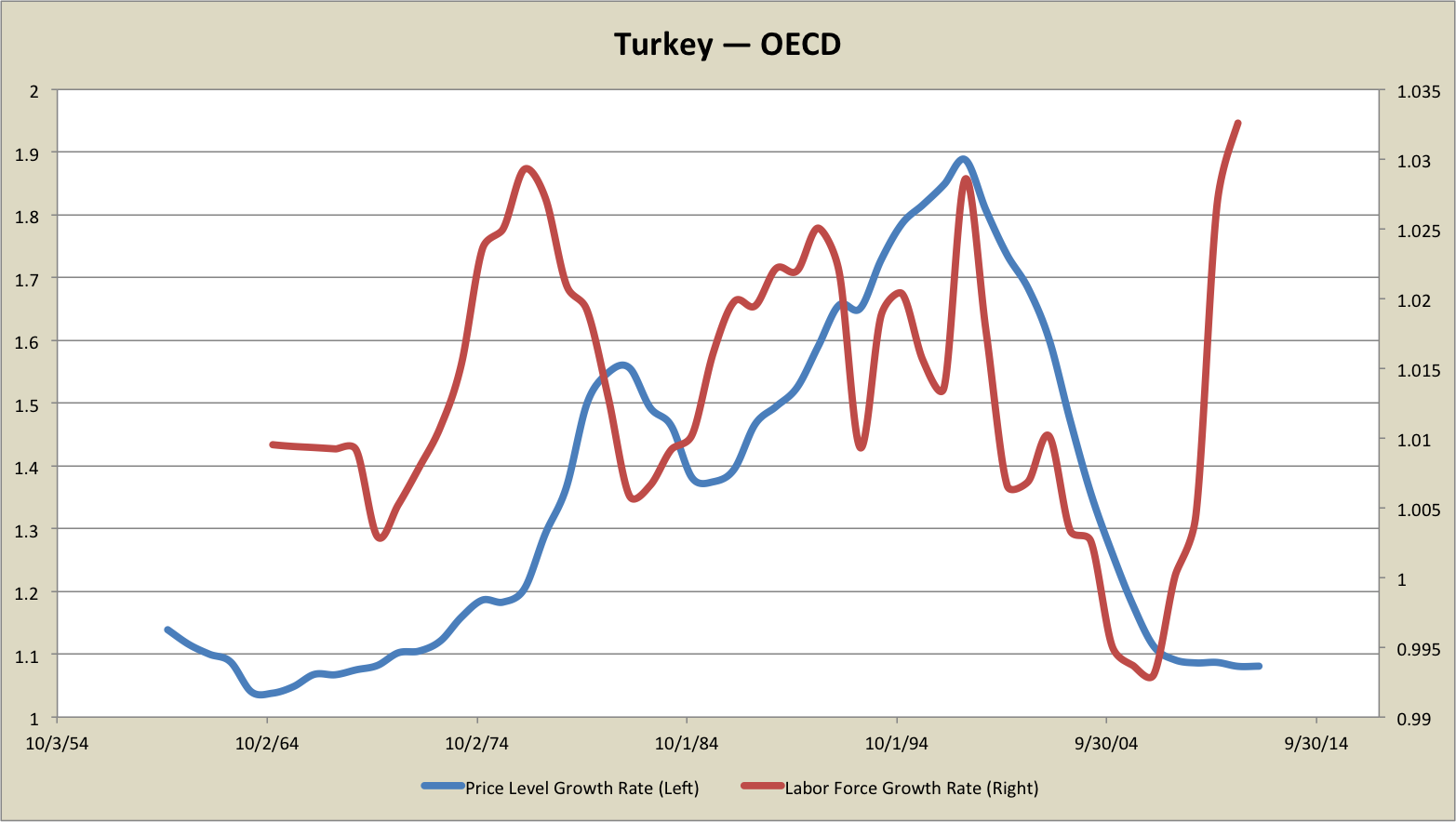

I’ve had a wonderful nemesis and helper the last few days in commenter Mark Sadowski, who challenged me to provide evidence for a demographic effect on inflation in international data. Mostly I made a fool of myself (twice actually, and not unusually). Looking at the graphs — after Sadowski helped me get them right! — I see support for a relationship between labor force demographics and inflation in the United States, Japan, Canada, and Finland. Italy is a strong counterexample — it disinflated in the middle of its labor boom. The rest you can squint and tell stories about. (I now have 14 graphs now.) Italy notwithstanding, the claim “it’s hard to disinflate when labor force growth is strong” looks more general than “inflation correlates with labor force growth”. Decide for yourself.

Sadowski is not much impressed by my demographic view of the Great Inflation. But he paid me the huge compliment of devoting time and his considerable expertise to testing my speculations. He writes

I took your set of eight nations plus the four from my original set of counterexamples that you excluded (West Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands), combined civilian labor force data from the OECD with CPI from AMECO, and computed 5-year compounded average civilian labor force growth rates and CPI inflation rates. The time periods ran from 1960-65 through 2007-12.

Then I regressed the average CPI inflation rates upon the average labor force growth rates. Five of the twelve were statistically significant, and all at the 1% level. The average civilian labor force growth rate and average CPI inflation rate were positively correlated in the U.S. and Japan, and negatively correlated in Spain, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

Next I conducted Granger causality tests using the Toda and Yamamato method on the level data over 1960-2012 for the U.S., Japan, Spain, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

The U.S. data is cointegrated, so although the majority of lag length criteria suggested using only one lag, since Granger causality in both directions was rejected at a length of one, I went to two lags based on the other criteria. The results are that CPI Granger causes civilian labor force at the 10% significance level but civilian labor force does not Granger cause CPI.

In Japan’s case civilian labor force Granger causes CPI at the 1% significance level but CPI does not Granger cause civilian labor force.

Granger causality was rejected in both directions for the other three countries.

In short, out of the 12 countries I looked at, only five have a significant correlation between average civilian labor force growth and average CPI inflation, and only two of five have a positive correlation. Of the five, only the two with positive correlation demonstrate Granger causality. But in the US case the direction of causality is in the opposite direction to that which you predict. Only Japan seems to support the kind of story you are trying to tell.

and follows up

I added your set of seven new nations (Canada, Finland, Greece, Italy, New Zealand, Switzerland and Turkey) plus seven additional nations (Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Korea, Norway, Poland and Portugal) to the set of 12 that I commented on last time. I did the same analysis as I did last time for this new set of 14, that is I combined civilian labor force data from the OECD with CPI from AMECO, and computed 5-year compounded average civilian labor force growth rates and CPI inflation rates. The time periods ran from 1960-65 through 2007-12 with the exception of Korea which started with 1967-72. I regressed the average CPI inflation rates upon the average labor force growth rates. Ten of the fourteen were statistically significant, and all at the 1% level with the exception of Poland which was at the 10% significance level. The average civilian labor force growth rate and average CPI inflation rate were positively correlated in Canada, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Korea, New Zealand and Norway and negatively correlated in Poland.

Next I conducted Granger causality tests using the Toda and Yamamato method on the level data over 1960-2012 (except for Korea which was over 1967-2012) for the ten countries which had statistically significant correlations.

In Finland, Poland and Korea civilian labor force Granger causes CPI at the 5% significance level but CPI does not Granger cause civilian labor force. In Greece CPI Granger causes civilian labor force at the 1% significance level but civilian labor force does not Granger cause CPI. In Iceland CPI Granger causes civilian labor force at the 10% significance level but civilian labor force does not Granger cause CPI.

So out of the 26 countries I have looked at, fifteen have a significant correlation between average civilian labor force growth and average CPI inflation with eleven of the fifteen having a positive correlation. Of the eleven with positive correlation six demonstrate Granger causality with three showing one way causality from civilian labor force to CPI and three showing one way causality from CPI to civilian labor force. Of the four with negative correlation one demonstrates Granger causality from civilian labor force to CPI.

Only three countries (Japan, Korea and Finland) out of the 26 support the kind of story you are trying to tell.

Mostly I am very grateful to Sadowski for his work.

Alas, I am not at all dissuaded from my view. At the margin I’m even a bit encouraged. The direction of Granger causality is not very meaningful here. (Granger causality, in the econometric cliché, is not causality at all but a statement about the arrangement of correlations in time. Expectations matter and near-future labor force growth is easy to predict, so there’s no problem if CPI changes can precede labor force changes.) I see some support for my thesis in the significant and usually positive correlations Sadowski observes in many countries. However, much as I am grateful, I don’t take this work as strong evidence either way. Sadowski overflatters my graphical analysis technique by translating it directly to an empirical model. Collapsing growth into overlapping 5-year trailing windows smooths out graphs that would otherwise just look like choppy tall-grass noise. But it creates a lot of autocorrelation unless the data is chunked into nonoverlapping periods. (Sadowski may well have done that! It’s not clear from the write-ups.) More substantively, to generate a good empirical model we’d have to think hard about other influences and controls that should be included. One wouldn’t model inflation as always and everywhere a univariate function of domestic labor force growth.

Maybe my view has been definitively refuted and I’m just full of derp! You’ll have to judge for yourself. In any case, I thank Sadowski for the work and food for thought, and for help and correction as I made a fool of myself.

I want to address some smart critiques by Evan Soltas:

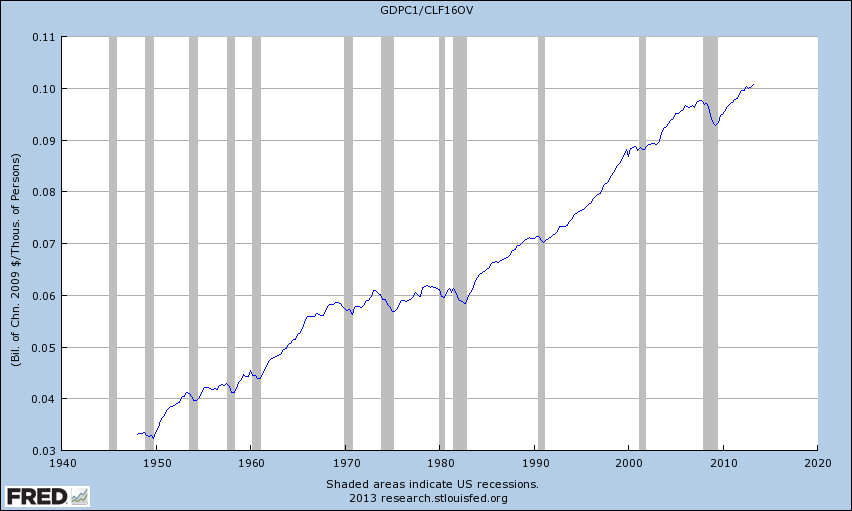

Consider a standard Cobb-Douglas production function: Y = zKαLβ. Consider a large and sustained shock to L, as Waldman shows. Consider, also, that the level of K has some rigidities, such that the level of K is not always optimal given the level of L, but that in a single shock to L, K will eventually approach the optimal level of K over some lag period. With this background, the marginal productivity of labor should drop and remain low over that lag period.

Now assume that real wages tend towards the marginal productivity of labor with a lag. What we should expect to see is that real wages should drop in the 1970s. Why? Surplus labor reduces the bargaining power of workers relative to that of employers. We don’t see that; real wages begin to fall after monetary policy tightens in the 1980s. My Cobb-Douglas model is also a bit limiting, but if anything, we might expect to see downward pressures on the labor share of income β. We don’t see that either — as compared to later periods, the 1970s appears to be a time of slightly stronger labor-share performance.

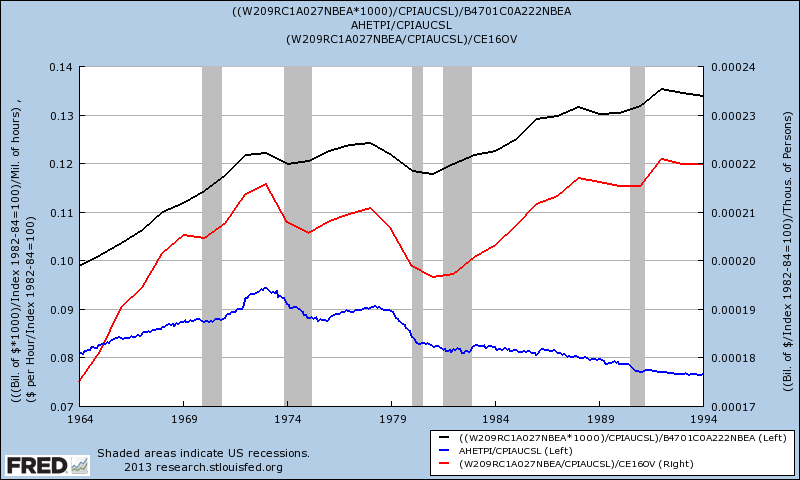

Under Soltas’ nice description of what I’ll call the “first order” effects of a demographic firehose, we should indeed expect real wages to fall relative to an ordinary population growth counterfactual. Did they? Yes, I think so. Let’s graph a few series.

The blue line is one of the series that Soltas graphed, CPI-adjusted hourly wages of nonsupervisory employees. They fell during the course of the 1970s in absolute terms. The black line is the broadest measure of hourly compensation I could compute, CPI-adjusted employee compensation divided by hours worked. It is essentially flat over the course of the decade, breaking a strong prior uptrend. The red line is CPI-adjusted compensation per employee. It fell in absolute terms over the decade.

Soltas suggests that compensation did not fall based on a graph of CPI-adjusted average manufacturing sector hourly wage, which rose over the 1970s. But manufacturing was simply an unrepresentative sector. (Those unions again?)

Overall, I think it’s fair to say that real wages did fall. They certainly fell relative to the prior trend, and probably in absolute terms. Still, looking at that black line, you might say they fell a bit less or more slowly than you might expect. More on that below.

Soltas also points to a strong labor share during the 1970s as disconfirmative, but that’s hard to interpret. Under the “first-order” demographic firehose story, we expect real wages per unit of labor to fall, but the number of units paid to increase. Which effect would dominate would depend on details of the production function. (It’s not clear that labor share was strong in the 1970s. Labor share seems to have declined over the decade from unusually high levels in the late 1960s.)

Let’s continue see the rest of Soltas’ critique:

Let’s simplify. Waldman’s thesis, stated uncharitably, is that a large increase in the labor supply acted as an inflationary pressure on the economy of the 1970s. I don’t see how that works. Show me the model. Less uncharitably, it forced a worse trade-off on the Fed, specifically forcing higher unemployment or higher inflation. I don’t see how that works, either. Unemployment might have been higher, but that would have put a deflationary pressure on the central bank, all else equal, given the exogenous surge in the labor supply.

Think about it this way: Whatever the Fed of the 1970s did in monetary policy, it faced an unstoppable surge in the labor supply. That should be a tremendous headwind against wage increases and broader inflation. You can argue that the capital stock wasn’t ready for the higher labor supply, and I would grant that point, but that should translate into a downward pressure on wages, not an upward pressure on inflation. It’s not an adverse supply shock.

Now we come to the “second order” story.

The piece of the model that Soltas isn’t seeing is rigidity. First, there is that most conventional rigidity, nominal wage stickiness. If real wages must decline for the labor market to clear, but nominal wages are sticky downward, then the only way to avoid unemployment is to tolerate inflation.

But in addition to nominal rigidities, there are real rigidities. All those kids in the 1970s graduating high school or college and entering the labor force had expectations about the kinds of lives they should be able to live when they got a job. They would not have been satisfied with increasing dollar wages, if those dollars could not support starting lives and families of their own, independent of Mom and Dad. Middle class labor force entrants then expected to be able to support a home, a car, even start a family on a single income.

Rigidities aren’t forever. Those expectations have evaporated over the past 40 years. That is the famous Two Income Trap, under which the necessities of “ordinary life” as most Americans define it now require two, rather than just one, median earner. But Rome wasn’t destroyed in a day. Baby boomers entered the labor force with real expectations. They were not mere price takers. But the declining marginal productivity in Soltas’ Cobb-Douglas production function meant boomers could not earn sufficient real wages to meet those expectations in a hypothetical perfect market. They faced precisely a supply shock [1], arising from each boomer’s own diminished capacity to supply relative to prior cohorts, for reasons entirely beyond their control. They would not be very happy about it. A tacit promise would have been broken.

To avoid social turmoil, the political system had to find ways of not disappointing the budding boomers’ expectations too abruptly. That implied some redistribution, from older workers and capital holders to new workers. Among other things, inflation can be a means of engineering covert redistributions. This is the part, I think, that puzzles Scott Sumner. High inflation reduces the real purchasing power of people living off of interest, and of people already employed who are slow or lack bargaining power to negotiate raises. That foregone purchasing power liberates supply, which becomes available to subsidize the real wages of the newly employed. Real GDP did not collapse during the 1970s, but the inflation created losers. The share of production that losers lost went to someone. I think that, among other mischief, it helped subsidize the employment of new workers at real wages below but not too far below what the generation prior had enjoyed.

We’ve seen that Arthur Burns was a genius, but I don’t think that any of this was conscious strategy. Like most real-world policymakers, Burns felt his way towards the least painful solution, then used his considerable intellect to justify what he found himself doing. When Burns tightened money, unemployment rose sharply and Greg Brady got mad that the jobs he was refusing wouldn’t pay enough to cover wheels and a pad across town from his annoying sisters. He started to smoke dope, get into politics, frighten his parents and neighbors. (We won’t even talk about J.J and the Panthers.) When money was loose and inflation roared, times were bad for everyone, which helped ease the sting. Greg’s job offers still paid less in real terms than he’d have hoped, but the money illusion made the numbers sound OK, and he could stretch the salary to move away, albeit into a smaller place than he had hoped. Carol and Mike breathed a sigh of relief, as did their congressman, Richard Nixon, and Arthur Burns.

If you’ve read all of this, there is something terribly wrong with you. I thank you nonetheless. As I said at the start, this will be my last episode of “That ’70s Show”, at least for a while. (Thanks @PlanMaestro!) I want to move on to other things. Do feel free to have the last word, in the comments or elsewhere.

[1] More abstractly, fix the median new worker’s market clearing real wage as our numeraire. Prior to a population boom, the median new worker supplies her labor for a particular bundle of goods and services. But in the population boom, because of the diminishing marginal productivity of labor (holding K constant), the median new worker cannot produce enough in real terms to purchase the same bundle. The worker’s demand curve has not changed at all: she remains willing to trade one unit of salary for one unit of consumption bundle, just as her predecessor did. But that trade is no longer available to her, because she herself is unable to supply real production in sufficient quantity to purchase those goods, despite expending her fullest effort. This is a supply shock, from the worker’s perspective, not a demand shock. The population boom is a shock to her ability to supply, which would be reflected by inflation of the cost of goods relative to the numeraire of her labor.

Update History:

- 11-Sept-2013, 1:55 p.m. PDT: “

Congressmancongressman“; “her fullestlesseffort”; Also, a while back, corrected (again) my persistent misspelling Sadowski’s name “SandowskiSadowski“