Hidden profits, hidden rents

Evan Soltas has a very good post on the explosive growth of the financial industry since the end of World War II. As a share of GDP, in terms of profits, and in terms of payroll, postwar America has been truly been a golden age for bankers, brokers, and fund managers.

In fact, it’s even better than it looks!

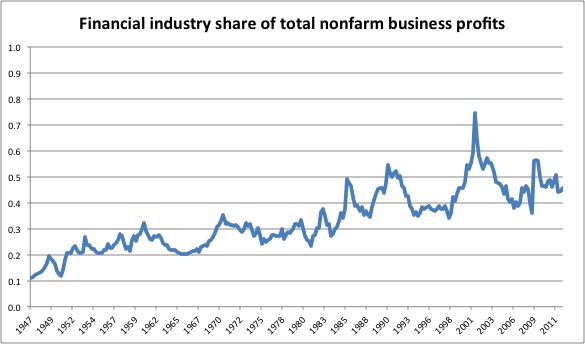

Soltas begins with a graph:

The graph above shows that the financial industry now makes roughly half of all nonfarm corporate profits in the U.S., a share which has risen five-fold since the end of World War II.

“Profit” is always something of a sticky subject. We talk about it all the time, like we have any idea what it means. Usually we don’t. There is, for example, the distinction between “accounting profit” and “economic profit”. Accounting profit is what a firm, under generally accepted accounting principles, can claim to be the earnings that accrue to shareholders. Economic profit is revenue that exceeds the true cost, defined as the value of the next-best opportunity, of all inputs. According to theory, in a competitive market, economic profits should be relentlessly pushed toward zero while accounting profits should stay positive but very near the broad market return on capital placed at comparable risk.

In general, only accounting profit is measured while only economic profit is interesting. When we think of economic profit, we need not restrict ourselves to shareholders, who represent just one class of claimants on an enterprise. Suppose there is an industry whose firms about break even in accounting terms, but whose unionized workers, even those without hard-to-find skills, capture salaries much larger than they likely would outside of the industry. Is the industry “profitable”?

In an economic sense, it is very profitable. It generates sales that far exceed the opportunity cost of its inputs. But for institutional reasons, those profits are captured by workers rather than accruing to equityholders, and so are missed by accounting measures. It’s pretty clear that, in its heyday, the US auto industry was like this. The industry generated a great deal more “value” than was captured by its shareholders. The internal negotiations between firm stakeholders over the distribution of economic profit has no bearing on the existence of that profit.

The financial industry is not heavily unionized, but the lack of a union doesn’t mean the struggle over the distribution of economic profit goes away, with shareholders automatically winning. In many industries, economic profit is far higher than accounting profit, with the difference captured by various sorts of insiders. And there is no industry in which the distribution of economic profit to employees is more institutionalized than in finance, where at large banks roughly half of firm revenue get distributed to employees, largely in the form of bonuses. Now, one can argue that the form in which compensation contracts are negotiated says little about whether the level of that compensation exceeds the opportunity cost of the work to recipients. Perhaps bank employees earn higher salaries on average than they could elsewhere as compensation for the bearing much of the risk of firm performance by accepting low base salaries and uncertain bonuses. But.

Economic profit creates an incentive for new entrants. Indeed, given how difficult it often is to measure the true cost of inputs, the best way to observe economic profit is to look for people banging at the door. And people do seem to be banging on the door in finance. Famously large fractions of Ivy league graduates — who can do anything, for whom “the world is their oyster” — end up taking finance jobs, despite very often having no specialized training in the field. I hope it will be uncontroversial to suggest that finance jobs are coveted. Those low base salaries delivered with a variable upside are, it turns out, not so low when compared with salaries in other industries. It is true that much of the “economic profit” earned by bank employees is delivered as a claim on a high-mean-value probability distribution rather than as a certain paycheck. But the opportunity cost of the input is mostly covered by the base. [1]

To the degree that financial firms’ economic profit is unusually captured by employees rather than shareholders, accounting-based estimates of finance’s profit share, like the one that Soltas presents above, will badly underestimate the share of economic profit captured by finance industry stakeholders as a whole. [2]

That an industry captures a lot of economic profit need not be a bad thing. After all, economic profit represents “value added”, the degree to which outputs are worth much more to people than inputs. However, we often divide economic profit into two components, the usually-transient good kind that results from innovations which leave firms a step ahead of their competition, and bad “rents” that result from capturing subsidies and/or restricting competition. To be fair, most successful firms get some of their economic profit both ways. But you’d need a great deal of faith in empirically invisible new value to explain the persistent and growing profit captured by finance, if its source isn’t predominantly rents. And, indeed, Soltas enumerates some of those:

Let’s run though the explicit subsidies: the mortgage-interest deduction and other homebuyer credits, student loan aid, federal guarantees on debt, the preferential tax rates on capital gains and dividends, interest on reserves at the Fed, and the FDIC guarantee. The financial industry also benefits from substantial implicit regulatory subsidies such as “too-big-too-fail.”

That’s a very good list. I’d add one more: the Federal Reserve’s policy of stabilizing the purchasing power of currency. Though stock markets and fancy derivatives get lots of press, most of the abnormal profits in finance are, I think, earned in debt markets. Financial firms borrow money and lend money. They underwrite debt issued by others and structure that borrow and lend. Financial rents seem related to scale and concentration. Debt-based financial intermediation is amenable to economies of scale in ways that equity-based funding is not. Rating agencies can get away with classifying debt products like beef, USDA Triple-A, and trillions of investment dollars flow accordingly. Investors are more idiosyncratic and more cautious with equities. “Too big to fail” is primarily a quality of credit markets — no one thinks that any bank is too big to suffer a stock-price decline. When financial firms extract rents via explicit government support, it is usually in order to ensure that bank creditors are made whole.

But debt finance exists in competition with equity finance. If I’m right that debt finance is a more fertile source of industry rents than equity, then ways that the state tilts the scale towards debt funding are part of the problem. Along with Felix Salmon, James Surowiecki, and many others, I’ve argued against the bias towards debt embedded in the tax system. But stabilizing prices also increases the relative attractiveness of debt. Absent price-level stabilization, the business cycle risk borne by diversified equity investors is somewhat counterbalanced by reduced risk from inflation, as price increases pass through to earnings and dividends over the medium term. If recessions tended to be inflationary, as they would for example under an NGDP target, this pass-through would amount to a very desirable countercyclical feature. Debt, on the other hand, would lose value in real terms during inflationary recessions. (For lower quality debt this loss would be partially offset by reduced risk of default.) The current practice of targeting inflation makes default-risk-free debt a nearly no-lose proposition regardless of macroeconomic performance, while accentuating the exposure of equities to business cycle risk.

There are lots of good reasons to reduce our dependence on the institution of debt in favor of more equity-like arrangements. Evolving towards a smaller financial industry less capable of capturing rents is another reason. Using the power of the state to stabilize the inflation rate is a bad idea, also for lots of reasons, including that the practice encourages debt finance and powerful banks.

[1] Even to the degree that supernormal paychecks are compensation for risk-bearing, part of the compensation should be recategorized as a return on shadow equity, rather than as a cost of labor input. One can decompose a bankers’ variable compensation into a cash payment plus funds that might have been paid but are instead invested on the employee’s behalf into the firm or a subdivision thereof. Much of bankers’ bonuses, the part that is compensation for bearing firm risk rather than paying for labor, should be viewed as a return on shadow equity that doesn’t show up in the formal equity accounts. When banks recruit employees to finance the firm with deferred compensation and then pay a performance-based return on that advance, it is quite similar to issuing new shares or outcome-contingent securities. The return eventually paid on those securities in excess of the original amount deferred ought to be considered distributed profit rather than labor compensation.

To highlight the murkiness of the dividing line between compensation and profit, consider two employees. One employee is paid at the beginning of the year in the form of firm stock, which will not “vest” (be made available) until the end of the year. The other is paid 20% less, but gets conventional cash payments and will receive an end-of-year bonus based on firm performance. Suppose the firm’s stock rises by 10% over the year, and our cash-paid employee receives a bonus worth 40% of her base salary. If you do the math, you’ll find that the cost to the firm of the two employees is almost the same. Both employees bore similar (although not identical) risk. Yet on the books, the first employee’s compensation will be smaller than that of the second employee, with the difference reflected in the earnings of the firm. Rewriting the first employees explicitly equity-based contract into a reduced-compensation-plus-bonus contract changes little of substance, but reduces the firm’s accounting profit (and tax basis!). Since compensation-plus-bonus is common in financial firms, reported profits are low relative to an world in which the variable basis for the compensation was recorded as equity. Yet recording the compensation as equity more accurately captures the division between compensation for labor and the compensation for risk-bearing that defines accounting profit.

Note that this analysis is unchanged if the motivation for the variable payment is to encourage performance, and is based on outcomes close to the employee, rather than firm-level performance. The employee is then compensated in equity in smaller, riskier subdivisions of the firm (and might require a higher salary “in stock” to compensate), but that does not alter the opportunity cost of her own employment or the fact that proceeds from good outcomes represent economic profit.

[2] Finance is unusual but not unique — see also health care, education, and government, together the “information asymmetry industry“.