Housing is a bitch.

A case can be made that divisive hot-button issues like inequality and immigration ultimately derive from housing dysfunction. Kevin Erdmann eloquently tells the tale. Matt Rognlie has famously argued that the increase in capital’s share of income, often blamed for inequality, is due largely to housing, once depreciation is taken into account. All of this reinforces the thesis of people like Ryan Avent, Edward Glaeser, and Matt Yglesias who have argued for years that housing supply constraints are to blame for high rents in powerhouse cities, and may constitute an important drag on productivity growth and a cause of macroeconomic stagnation. (See also Paul Krugman, quite recently.) Several of these writers argue that cities should eliminate restrictive zoning and other regulatory barriers to development, then let the free-market create housing supply. In a competitive marketplace, high prices are supposed to be their own cure. Zoning restrictions, urban permitting, and the de facto capacity of existing residents to veto new development are barriers to entry that prevent the magic of competition from taking hold and solving the problem.

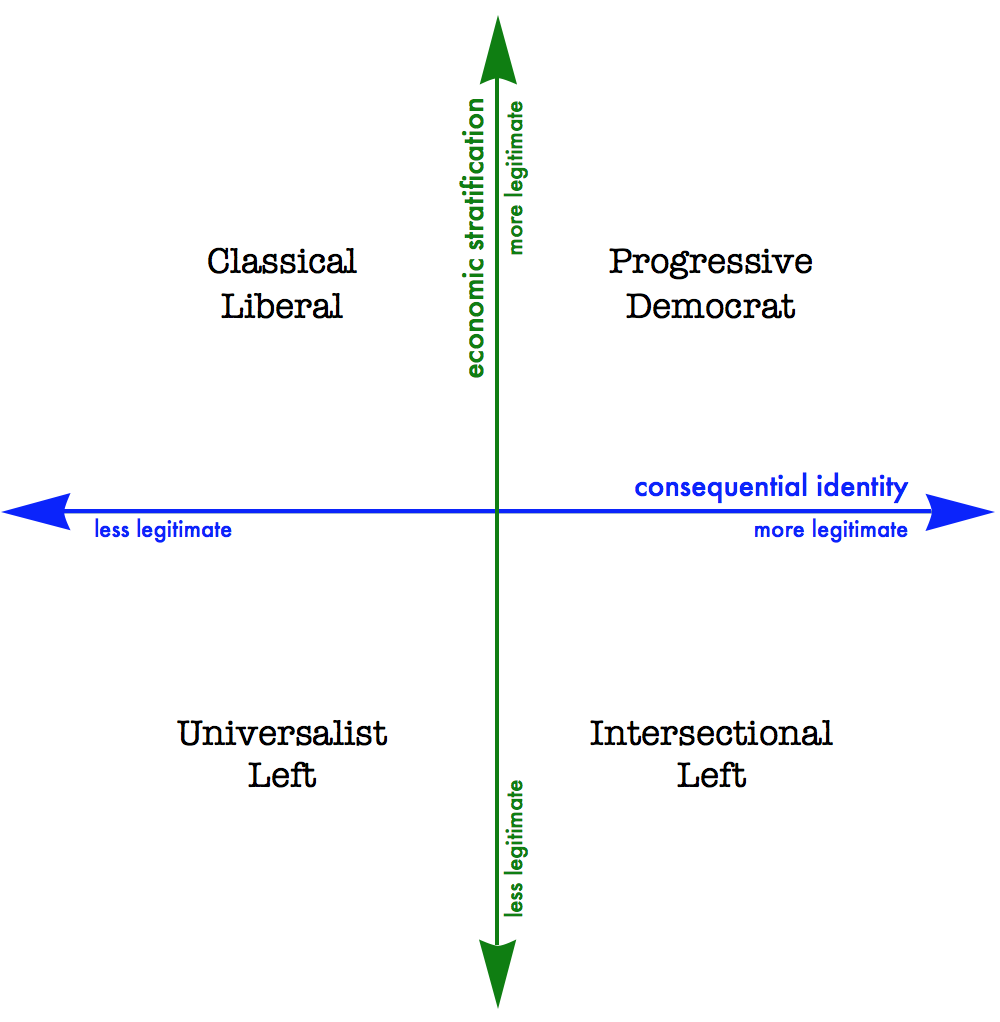

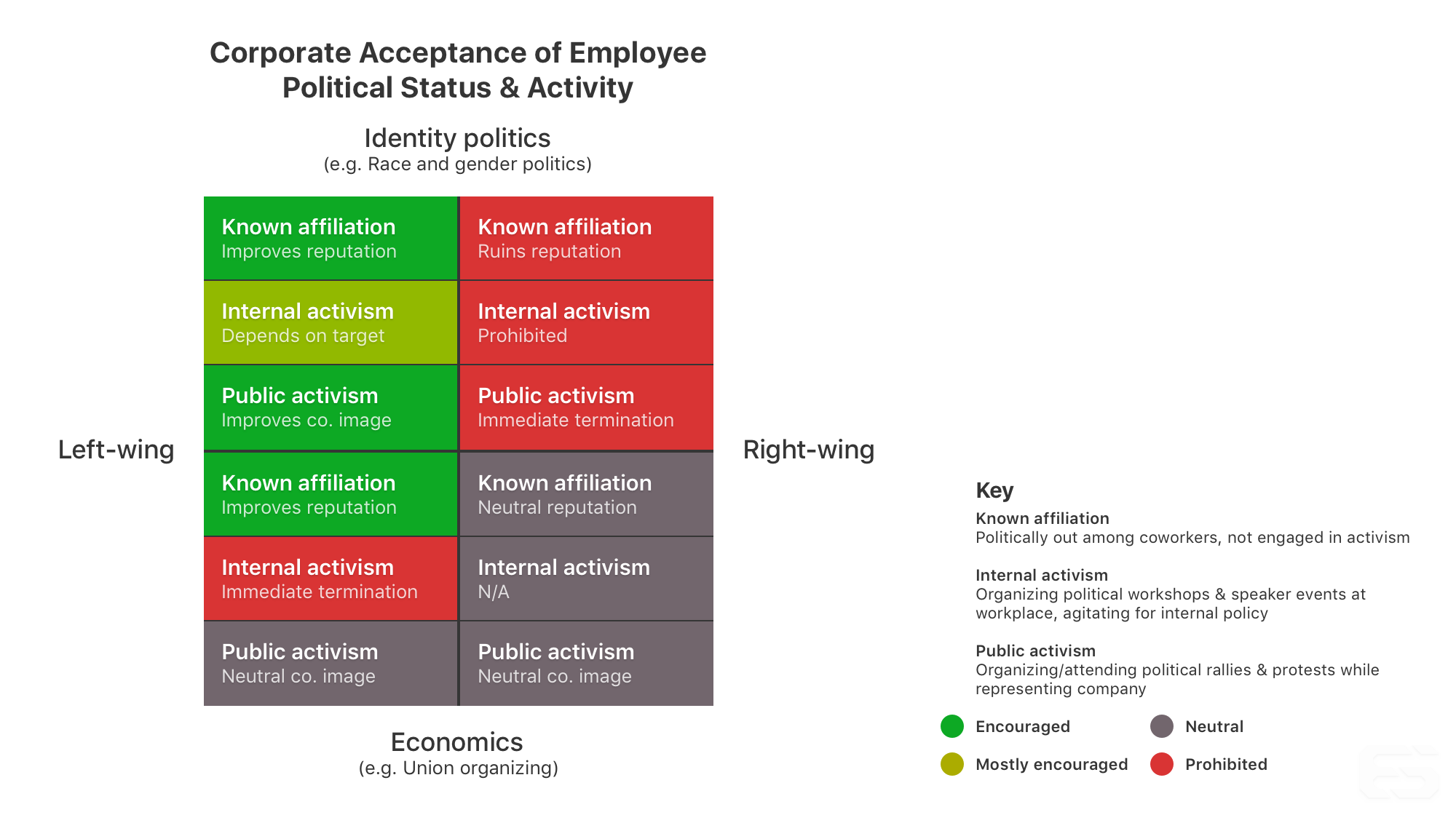

My view is that the “market urbanist” diagnosis of the problem is more persuasive than its prescription for addressing it. As a positive matter, they just won’t win the political fights they propose. On normative grounds, I’m not sure that they should. The market urbanists present themselves as capitalist deregulators but I think they can be described with equal accuracy as radical redistributionists. The customary property rights surrounding homeownership in many cities and suburbs include much more than the use of a square of earth and whatever is built on it. Existing homeowners bought into particular neighborhoods in large part because of their “character”, which includes nice-sounding things like walkability or “charm”, as well as not-so-nice-sounding things like access to exclusionary education. Newer residents have bought and paid for those amenities, while older residents may feel they have earned them by helping to create them. Economists describe houses as a form of capital that provides a stream of services, rather than a cash flow, to owner-occupants. We should also describe the arrangement of neighborhoods as a form of capital that provides services people value. Property owners have disproportionate use of, and, informally, enjoy substantial control rights over this “neighborhood capital”, and these benefits have been capitalized into residential real-estate prices. (Location, location, location!) “Zoning reform” is an anodyne way to describe an expropriation of those customary rights. It amounts to diminishing residents’ ability to preserve or control the evolution of their neighborhoods, in order to challenge the exclusivity on which the value of existing neighborhood amenities may be based.

Market urbanists sometimes respond that eliminating restrictions should, in economic terms, be good for existing property owners. Suppose I own a plot of land, and today I’m only allowed to have a two story house on it. If tomorrow I suddenly have the right to build ten stories, but I can still keep the little house if that’s what I prefer, the new option can only improve my property’s value, right? Surely de-zoning would be a windfall for property owners, as land prices would include part of the capitalized stream of rents from the ten urban lofts that could now, potentially, be built there.

This is unpersuasive “partial-equilibrium” reasoning, which explains why homeowners are usually unpersuaded. Any given property owner rationally wants restrictions lifted on the use their own property, but lifting restrictions on neighbors’ use of their properties creates risks and costs. The ultimate effect of a general upzoning is hard to predict and may not be positive for incumbents, especially when potential impairment of existing amenities — “neighborhood capital” — is factored in. Far from being a sure gain to existing residents, upzoning is a form of risky investment, the proceeds of which will be shared with developers and new residents, the costs of which will be concentrated on people whose financial statements and human lives are deeply exposed, with little diversification, to the quality of their neighborhoods. Even if, in aggregate, land values increase, densification of an existing neighborhood creates risks for individual property owners they many not wish to bear. If an apartment block is built next door, my old neighbor may have gotten rich from selling, but my plot may not be suitable for putting up yet another tower, and my home may be worth less for its busy, unquaint new neighbor. People experience individual not aggregate outcomes, and individual outcomes are usually riskier than aggregate outcomes. Absent some insurance mechanism, it is rationally hard to persuade individuals to consent to policy changes that, in aggregate terms, would meet a return-to-risk hurdle but at an individual level might not. When market urbanists point to how much more productive and awesome the city as a whole might become, they are missing this point.

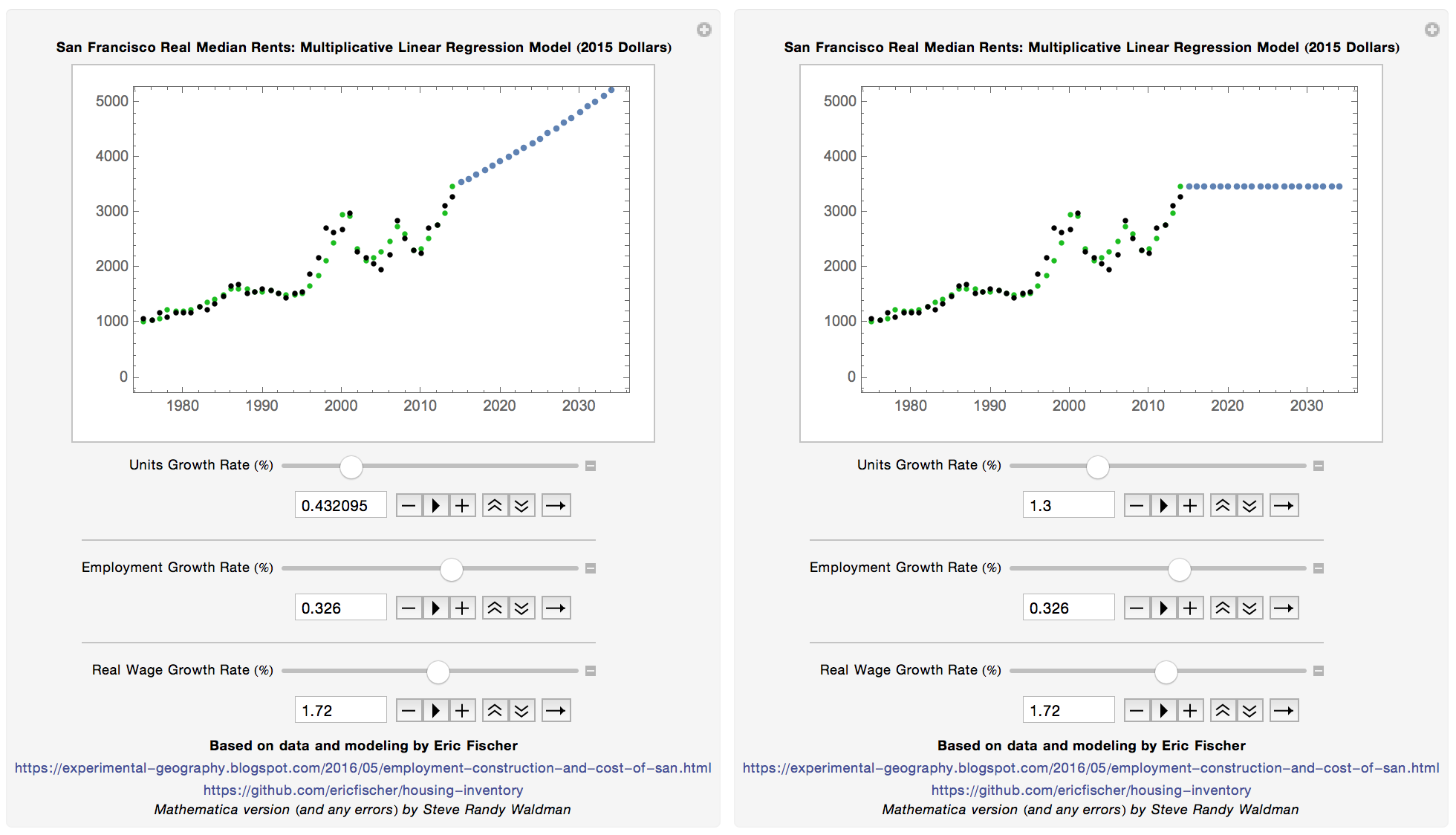

Finally, whatever economic gains might accrue to existing property owners from rezoning has to be traded off against a huge cost, the loss of existing monopoly rents. If you buy a home in San Francisco today, the last thing you want to happen is for the housing affordability problem to be solved next year. If apartment prices become reasonable, you’d find yourself with a huge financial loss and an underwater mortgage. Residential property is expensive in power cities because it includes the capitalized value of the large income streams one can earn from accepting tenants. (Now more than $5K/month for the median 2BR apartment in San Francisco I hate this city.) Making housing affordable means that value goes away. High rents are like poverty at the Brookings Institution, a problem we claim we desperately want to solve but don’t really want to solve because the things we would have to do to solve it would be costly and disruptive to the people whose interests get termed “we” in a sentence like this one. So we make other stuff up, hey, how about a little affordable housing requirement with a poor door you’ll have a 1/1600 chance of getting into? The home cartel is stable by virtue of regulatory coordination, which cannot be undone by adversarial political action because cartel members practically define the enfranchised municipal community.

Home is where the cartel is. I use the word “home” not “housing” advisedly. Homeowners understand their actions not as monopolizing the housing market but as protecting their homes and neighborhoods from the market. The libertarian “deregulatory” rhetoric by which market urbanists sometimes make their case is counterproductive. Telling people to think of their homes as a commodity upon which market forces should be brought to bear in order to ensure production of housing services at competitive prices is obtuse. People purchase property, rather than rent, largely to gain security and control, to escape the vicissitudes of the market. The worst place to emphasize “deregulation” is in dense urban environments, where almost every sort of action has spillovers. Construction in dense cities will always be heavily regulated, and should be. There can be good regulation and bad regulation, but talking about “deregulation” in an urban context is just self-branding. Dense cities in developed countries expand their housing stock as a policy choice, not because anonymous producers respond to price signals. Price signals — high market prices — give cities the option to expand their housing stock without financial subsidy by reregulating to attract developers. But nobody is dumb. You actually have to persuade an urban polity to choose to permit development, in a particular place, over the objections or with the consent of diverse stakeholders.

The deregulatory narrative not only fails to help, it very directly hurts. If you frame your solution as being about “freeing markets”, you are likely to oppose rent control on naive and misleading Econ 101 grounds. Price controls, you have been taught, create scarcity, by eliminating the incentive to produce up to the market-clearing quantity. But to claim “the rent is too damn high” implies directly that housing prices are already above the level that would inspire further production, if there weren’t other regulatory barriers. In the prosperous cities where we perceive housing crisis, market-rate housing is already priced at levels that would attract further development, if only the polity could be persuaded to allow it. New construction is market-rate housing: It is almost never subject to rent controls. The existence of rent controls on older buildings does suggest a danger that housing built today might someday be placed under rent controls too, sure. But that risk is already priced into market-rate development. If market-rate apartments sell for substantially more than their physical cost of replacement, then the market deems the risk of future value-impairing rent regulation to be sufficiently small, or sufficiently distant, or the present demand for housing to be sufficiently acute, as to cover that risk. The Econ 101 case against rent controls only holds if the threat of controls prevents the market value of newly produced rentable properties from substantially exceeding the cost of development after regulatory hurdles have been overcome. [1] This is not what we observe in real life. Impaired prices are simply not the binding constraint on new development. Market urbanists unnecessarily make enemies of a critical constituency, tenants in rent-stabilized apartments who have extraordinarily much to lose. Renters should be cities’ natural advocates for new supply. But when proposals to build come bundled with an ideology that would price people out of their current homes, renters’ enthusiasm is unsurprisingly muted. [2]

Market-centered narratives about homeownership are the source of housing supply problems at least as much as they might suggest solutions. As Daniel Hertz has observed (ht Ryan Cooper), there is a fundamental contradiction at the heart of housing capitalism. We encourage people to take on highly leveraged, undiversified exposure in homes with promises that they are good “investments”, meaning they will increase or at least retain their values over time. We also claim that housing is a consumption good that should be efficiently provided, a good for which competitive markets should expand supply to drive prices down to a technologically declining marginal cost of production. Housing cannot be both of those things at once. Much of the work we have to do if we wish to increase housing supply is to deemphasize the housing-as-investment narrative in favor of housing-as-consumption-good. Price ceilings would prevent windfall investment gains (and so investment-motivated purchases). Price ceilings would also new prevent buyers from becoming levered against much-higher-than-replacement-cost home values, and therefore lobbyists for housing scarcity. Surprisingly from an Econ 101 perspective, the best way to encourage housing supply might be to cap home prices, at a level sufficiently above physical construction cost to keep development profitable when consumption demand is strong, but no higher than that, to discourage the use of homes as speculative financial investments and to prevent scarcity rents from getting capitalized into prices.

I don’t advocate trying to impose price ceilings on existing market-rate housing. That would be an expropriation at least as unfair and politically challenging as eliminating zoning restrictions. Plus, maximizing the quantity of housing supplied cannot be our sole, overriding objective. There is much to be said for encouraging “neighborhood capital” production, incentivized in part by the prospect of rising home values, as a means of increasing quality of life and sheer aesthetic joy, despite the “NIMBY-ism” it rationally provokes. There are trade-offs. However, when we build new neighborhoods, we might want to be open to new regulatory ideas. As long as builders and buyers know the rules of the game up front, anything is fair. Experimentation should be encouraged. “Deregulation” cannot be our touchstone. The word is meaningless (it sneaks in some definition of neutrality which is wholly arbitrary), and discourages creative thinking or even looking around to see what works.

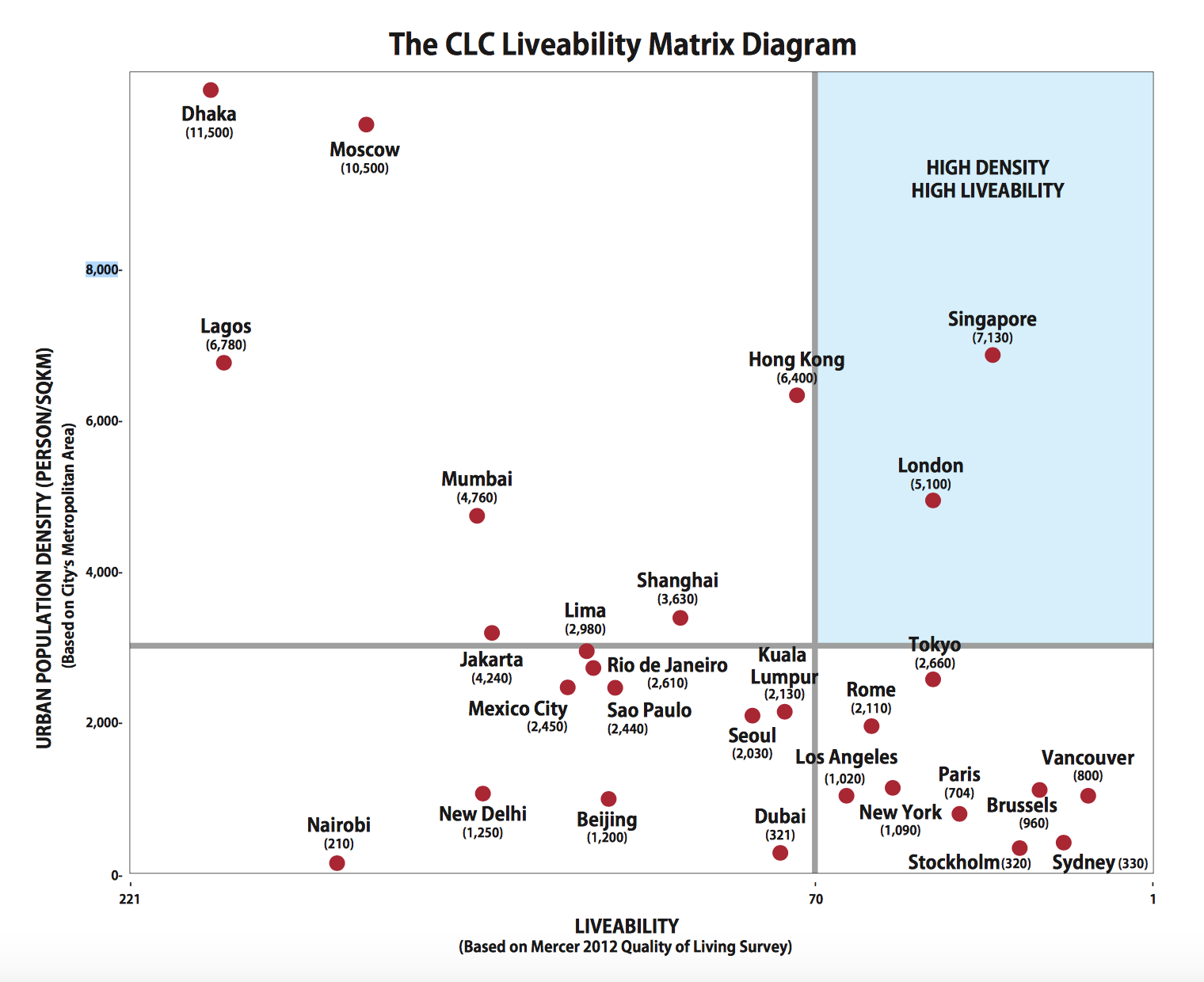

I don’t know what will work. But, looking around a bit, I’d suggest we take a look at two particularly promising examples. The housing policies of Singapore and Germany couldn’t be more different. But both countries have been remarkably successful.

Singapore never solved the problem we are banging our head against, how to take existing prosperous neighborhoods and make them more dense. It never tried. Instead, Singapore expanded its housing supply, at remarkable speed and scale, by building out extremely dense but nevertheless green, livable, and attractive “new towns“. Rather than restricting our attention to putting more housing in existing desirable neighborhoods, why not follow Singapore and build new neighborhoods, and when we run out of space for those, new ring cities? Singapore has done a ton of experimenting, in regulation, architecture and urban design, in putting greenspaces around (and on) increasingly creative high-rise developments. Obviously, Singapore is very different, socially and politically, than the United States and other Western countries. Some things won’t (and shouldn’t) translate. But we still have a lot to learn from their experience. Are we really incapable of building new, compact, microcities without their becoming Cabrini-Green or the banlieues of Paris?

Germany’s virtues are less sexy than Singapore’s sci-fi eco-towers. But they are great virtues nonetheless. Somehow, Germany has managed to avoid the price booms that in so many countries (including the Scandinavians) have segregated society between those who were homeowners at just the right times and those who were not. Germany’s path is ideologically mixed. On the one hand, German property owners have a right to build within broad planning parameters. On the other hand, what we in the United States call rent controls are universal in Germany. (German leases are implicitly “rent stabilized”. Berlin has recently begun an experiment with old fashioned administered prices.) Lending for home buying is regulated and conservative in Germany, preventing joint credit/housing booms. (You’ll recall that German banks had to dive headlong into American junk housing securities and Southern European bonds to get themselves into trouble, since their own economy wouldn’t produce enough product.) Homeownership and renting are roughly balanced, and home prices have had no tendency to increase dramatically. Homes in Germany are what a naive economist might predict they should be, a very durable consumption good that provides a stream of housing services, not a ticket to financial gain at all. Germany’s cities are very affordable relative to their counterparts elsewhere in Europe and in the United States. Germany’s housing success seems boring, in the way that your chest might seem boring to a guy who has just been stabbed and is spurting blood from a ventricle. Boring, but wonderful.

Boring Germany, sci-fi Singapore, or something else entirely. Urban housing is a really hard problem. We’ll need lots of inspiration. That economics textbook might help a little, but don’t try to use it as a cookbook.

FD: I’m very grateful to live in a rent-stabilized apartment in San Francisco.

[1] One might be tempted to argue that regulatory hurdles are themselves a “cost”, so very high prices are necessary to incentivize developers to do the necessary lobbying and lawyering. If that were a good model, the housing problem in places like San Francisco and New York would already have been solved. There is no fixed cost of permission that high property values can overcome. The political process doesn’t set a price in lobbying and paperwork and bribery and then let the supply of permits and variances expand elastically once that price is met. A better approximation is that the political process fixes a quantity and uses price to ration permission, so that any additional willingness of developers to bear regulatory costs feeds into a bidding war that feeds lawyers and architects and bureaucrats (and generates free amenities to buy off the neighbors!) but does not greatly expand the number of permits granted, or, therefore, the quantity of dwellings supplied.

[2] There is one channel through which existing rent control really might discourage new supply in high market-price neighborhoods, and it has nothing to do with supply and demand diagrams. In order to increase the housing stock of an existing, well-utilized neighborhood, one often has to knock down buildings that exist in order to put up something denser and/or taller. The prospect of this sort of “redevelopment” is always going to anger humans, who sometimes grow attached to their homes. For people in rent controlled housing in very hot markets, the threat of redevelopment is existential. Rent control in America is mostly “second generation rent control” or “rent stabilization”. You rent at market rates, or even some premium to market rates, but thereafter rent increases are tied to some administrative measure of inflation. If the building that you’ve lived in for years gets torn down to build something new, the clock starts over and you have to rent at current market rates, even if you find a new rent stabilized apartment. Many (probably most) current residents of rent-stabilized apartments would not be able to afford to live in their neighborhoods at market rates, or even in their cities. “Affordable housing” programs (of which I have a low opinion) may offer sanctuary to some of the displaced, but they offer at best an uncertain prospect. Because the stakes are so high, residents of rent-stabilized apartments become a political constituency implacably opposed to redevelopment. The long-tenure rent-stabilized are a precise mirror image of property owners who prefer constrained supply to support prices. Both have rents (in the economist’s sense of the word) to protect, benefits that markets would compete away under a different set of regulations. Both perceive securing those rents not as cashing in, but as protecting their homes and their families. Both will work (in coalition with one another) to prevent redevelopment, densification, upzoning, etc. “Reduces the future flexibility of neighborhoods” may be a colorable reason to have opposed rent stabilization back in the day. You may be cruel enough to simply wish to end it abruptly now, on the theory if those people are kicked out anyway they’ll have nothing left to oppose. You may wish that, but if you are smart you will shut up about it.

Update History:

- 25-August-2020, 1:30 p.m. EDT: “…when potential impairment of existing amenities…”

- 23-October-2024, 4:15 p.m. EDT: “…the capitalized value of the large

incomes income streams…”; “People purchase property, rather than renting rent, largely”