Greece is a remarkable country full of wonderful people, but along dimensions of development and governance, the place is plainly pretty fucked up. It has been fucked up that way for a long time, for decades at least. This has never been secret. Anyone who has visited Athens knows it has far more in common with Bucharest or Istanbul than with orderly Western European capitals. In the run up to Greece’s joining the Euro, everyone who wanted to know knew that Greece’s qualifications to join the Eurozone were, shall we say, ambitious. Mainstream establishment banks “helped” Greece and other Southern European countries with accounting fudges that, while perhaps obscure, were not secret even at the time. Despite protestations when these deals hit the news in 2010 that officials were “shocked, shocked”, they were explicitly blessed by the agency that compiles the statistics on which Eurozone entrance was based in 2002 and Greece’s gaming was extensively reported in 2003 (ht Heidi Moore, both cites). The Euro was and ought to be primarily a political enterprise. In order to sell the common currency to Northern European elites, its architects required Eurozone members to meet strict “convergence criteria” and especially the requirements of the Stability and Growth Pact. But in practice, those criteria have always been interpreted flexibly. Most Eurozone members have broken their promises at one point or another, including both Germany and France. The Euro was a unification project, and erred (not unreasonably, I think) on the side of building a big tent.

Germany and France may have missed their Stability and Growth commitments now and again, but they are not fucked up like Greece is. Greek governments — not the current, much maligned Syriza, but decades of its predecessors — treated the state like a teat from which clients and friends of electoral victors might suck. The Greek state has been a shady, opportunistic borrower, no doubt, the kind of character no one would lend money to with any great expectation of seeing it back.

And yet, that’s precisely what bankers in the relatively not-fucked-up Eurozone countries did! These people were not naïfs. They knew the Greek state was sketchy. But precisely because it was sketchy, prior to the financial crisis its debt paid slightly higher interest rates than that of safer Eurozone sovereigns. European banking regulations attached zero risk weights to all EU sovereigns, rendering it nearly costless for banks to simply manufacture deposits to purchase sovereign debt. Eurozone sovereigns were default-risk-free as a regulatory matter and currency-risk-free from the perspective of Eurozone banks. The European financial system was architected to make lending to Greece — and Spain and Portugal and Italy — a money machine for bankers with little career risk over a medium term. Sketchy credits tend to punch above their weight in terms of volume of issuance, so there was a lot of nice paper to buy. The bankers who lent to these states understood perfectly well that there was in fact a long-term risk, an uncertainty, a constructive ambiguity. They lent anyway, and took home very nice salaries and bonuses for doing so. It was conventional to lend, the mainstream consensus was that credit risk was over and worry warts were old-fashioned, Europe was strong and would work this out. If the worry warts turned out to be right, it was likely years away, IBGYBG.

When the game was up, when the global house of credit cards collapsed in the late Aughts, European leaders had a choice. They had knowingly and purposefully brought weak states into the Eurozone, because they genuinely, even nobly, wished to build a large, strong, United Europe. When they did so, they understood there would be crises. A unified Europe, they had always claimed, would be forged one crisis at a time. The right thing to have done for Europe at this point would have been to point out the regulatory errors and misaligned incentives that encouraged profligate lending and enabled corruption and waste among borrowers, and fix those. Banks that had made bad loans would acknowledge losses. The banks themselves would have to be restructured or bailed out.

But “bank restructuring” is a euphemism for imposing losses on wealthy creditors. And explicit bank bailouts are humiliations of elites, moments when the mask comes off and the usually tacit means by which states preserve and enhance the comfort of the comfortable must give way to very visible, very unpopular, direct cash flows.

The choice Europe’s leaders faced was to preserve the union or preserve the wealth, prestige, and status of the community of people who were their acquaintances and friends and selves but who are entirely unrepresentative of the European public. They chose themselves. The formal institutions of the EU endure, but European community is now failing fast.

It is difficult to overstate how deeply Europe’s leaders betrayed the ideals of European integration in their handing of the Greek crisis. The first and most fundamental goal of European integration was to blur the lines of national feeling and interest through commerce and interdependence, in order to prevent the fractures along ethnonational lines that made a charnel house of the continent, twice. That is the first thing, the main rule, that anyone who claims to represent the European project must abide: We solve problems as Europeans together, not as nations in conflict. Note that in the tale as told so far, there really was no meaningful national dimension. Regulatory mistakes and agency issues within banks encouraged poor credit decisions. Spanish banks lent into overpriced real estate, and German banks lent to a state they knew to be weak. Current account imbalances within the Eurozone — persistent and unlikely to reverse without policy attention — implied as a matter of arithmetic that there would be loan flows on a scale that might encourage a certain indifference to credit quality. These were European problems, not national problems. But they were European problems that festered while the continent’s leaders gloated and took credit for a phantom prosperity. When the levee broke, instead of acknowledging errors and working to address them as a community, Europe’s elites — its politicians and civil servants, its bankers and financiers — deflected the blame in the worst possible way. They turned a systemic problem of financial architecture into a dispute between European nations. They brought back the very ghosts their predecessors spent half a century trying to dispell. Shame. Shame. Shame. Shame.

Until the financial crisis, people like, well, me, were of two minds about the EU’s famous “democracy deficit”. On the one hand, I believe that good governance requires accountability to and participation of the broad public. On the other hand, before the crisis, I was willing to cut the Euro-elite a lot of slack. I’m an American born in 1970, but my life is largely framed and circumscribed by events in Europe during the Second World War. I grew up on a diet of “never again”. I am writing these words from my grandfather’s villa on the Romanian Black Sea, which my mother worked doggedly to recover in an act of sheer vengeance for what this continent’s history did to her father. I was inclined to support Europe’s democratic fudges when they were about diminishing and diffusing the still palpable possibility here of reversion to ethnonational conflict. To see European institutions deployed precisely and with great force in the service polarization across national borders has radicalized and made a populist of me (as have analogous betrayals among the political leadership of my own country). If I were Greek, I would surely be a nationalist now.

With respect to Greece, the precise thing that European elites did to set the current chain of events in motion was to replace private debt with public during the 2010 first “bailout of Greece”. Prior to that event, it was obvious that blame was multipolar. Here are the banks, in France, in Germany, that foolishly lent. Not just to Greece, but to Goldman’s synthetic CDOs and every other piece of idiot paper they could carry with low risk-weights. In 2010, the EU, ECB, and IMF laundered a bailout of mostly French and German banks through the Greek fisc. Cash flowed into Greece only so it could flow out to rickety banks. Now, suddenly, the banks were absolved. There were very few bad loans left on the books of European lenders, everyone was clean, no bad actors at all. Except one. There were the institutions, the “troika”, clearly the good guys, so “helpful” with their generous offer of funds. And then there was Greece. What had been a mudwrestling match, everybody dirty, was transformed into mass of powdered wigs accusing a single filthy penitent (or, when the people with their savings in just-rescued banks decide to be generous, a petulant misbehaving child). [antidote]

Among creditors, a big catchphrase now is “moral hazard”. We cannot be too kind to Greece, we cannot forgive their debt with few string attached, because what kind of precedent would that set? If bad borrowers, other sovereigns, got the idea that they can overborrow without consequence, if Spanish and Portuguese populists perceive perhaps a better deal is on offer, they might demand that. They might continue to borrow and expect forgiveness, and where would it end except for the bankruptcy of the good Europeans who actually produce and save?

The nerve. The fucking nerve. Lenders, having been made nearly whole on their ill-conceived, profit-motivated punts, now fear that if anybody is nice to somebody who doesn’t deserve it, where will it end? I’d resort to that cliché about chutspa, the kid who murders his parents then seeks leniency ‘cuz he’s an orphan. But it’s really too cute for the occasion.

For the record, my sophisticated hard-working elite European interlocutors, the term moral hazard traditionally applies to creditors. It describes the hazard to the real economy that might result if investors fail to discriminate between valuable and not-so-valuable projects when they allocate society’s scarce resources as proxied by money claims. Lending to a corrupt, clientelist Greek state that squanders resources on activities unlikely to yield growth from which the debt could be serviced? That is precisely, exactly, what the term “moral hazard” exists to discourage. You did that. Yes, the Greek state was an unworthy and sometimes unscrupulous debtor. Newsflash: The world is full of unworthy and unscrupulous entities willing to take your money and call the transaction a “loan”. It always will be. That is why responsibility for, and the consequences of, extending credit badly must fall upon creditors, not debtors. There is one morality tale that says the debtor must repay, or she has sinned and must be punished. There is another morality tale that says the creditor must invest wisely, or she has stewarded resources poorly and must be punished. We get to choose which morality tale we most use to make sense of the world. We do, and surely should, use both to some degree. But if we emphasize the first story, we end up in a world full of bad loans, wasted resources, and people trapped in debtors’ prison, metaphorical or literal. If we emphasize the second story, we end up in a world where dumb expenditures are never financed in the first place.

But don’t the Greeks want to borrow more? Isn’t that what all the fuss is about right now? No. The Greeks need to borrow money now only because old loans are coming due that they have to pay, and they have been trying to come to an agreement about that, rather than raise a middle finger and walk away. The Greek state itself is not trying to expand its borrowing. Greece’s citizens and businesses would like to expand the country’s borrowing indirectly, by withdrawing Euros from Greek banks that the Greek banks won’t be able to come up with unless they are allowed to expand their borrowing from the ECB. That is, Greece’s citizens are in precisely the place France’s citizens and Germany’s citizens were in 2010, at risk that personal savings maintained as bank deposits will not be repaid. Something was worked out for French and German citizens. Other than resorting to the ethnonational stereotypes that European elites have now revived in polite company, what is the justification for a Greek schoolteacher losing her savings that wouldn’t have applied just as strongly to a French schoolteacher five years ago? Because Greeks are responsible, as individuals, for what the governments they elect do? Well, then I deserve to be killed for what my government has done in Iraq and elsewhere. Is that where we want to go?

If citizens aren’t going to be held responsible for their governments’ bad debts, how will sovereigns borrow at all? Well, how do firms raise equity, when an equity claim makes no promise whatsoever that any cash will be returned? People invest in shares not because they have any sword of Damocles to hold over the enterprise, but because they believe the firm will engage in activities sufficiently productive that throwing some cash back to investors will not be burdensome, and because firms know repayment enhances access to continued finance. The same is true of sovereigns like the United States or the UK, which borrow easily in currencies they can print any time. Nothing prevents the US from conjuring $100T USD and handing it out to citizens, engineering a one-time inflation that leaves outstanding bonds nearly worthless. It wouldn’t even constitute a default. But the US has organized itself in ways that persuade creditors that their funds will be treated reasonably. Inflexible debt sows seeds of coercion and enmity between borrower and lender. Equity-like arrangements, including “debt” denominated in securities issuable at will by the debtor, require and encourage trust and collaboration. Sovereign debt in particular should always look like the latter, not the former, given the regularity with which government borrowings are disbursed into insiders’ bank accounts rather than used to aid the publics who might be pressured to foot the bill.

Greece should see its debts forgiven, pretty much wholesale. That forgiveness should be understood as a default, with future investors warned. Insured deposits in Greek bank accounts should be made whole, uninsured deposits should be “bailed in”, Greece’s banking system should be integrated into a much more carefully regulated European banking system that eschews investment in individual sovereigns entirely, Germany as much as Greece. Let sovereigns sell securities to the market, where incentives for careful credit allocation are sharper than they are within banks. Let European banks hold only claims against the ECB when they want a risk-free instrument. If Spain or Portugal or Italy wish to haircut or repudiate their existing debt, let them, at cost of future market access. Sovereigns have an option to default full stop. Investors in sovereign securities must price that. If perceived credit risk leaves public finance too expensive Europe-wide, then the EU should develop a mechanism whereunder states are permitted to sell equity securities to the ECB up to a fixed limit, set uniformly across Europe in per capita terms.

I’ll end this ramble with a discussion of a fashionable view that in fact, the Greece crisis is not about the money at all, it is merely about creditors wresting political control from the concededly fucked up Greek state in order to make reforms in the long term interest of the Greek public. Anyone familiar with corporate finance ought to be immediately skeptical of this claim. A state cannot be liquidated. In bankruptcy terms, it must be reorganized. Corporate bankruptcy laws wisely limit the control rights of unconverted creditors during reorganizations, because creditors have no interest in maximizing the value of firm assets. Their claim to any upside is capped, their downside is large, they seek the fastest possible exit that makes them mostly whole. The incentives of impaired creditors are simply not well aligned with maximizing the long-term value of an enterprise.

If it were 2009, I might have been persuaded that the corporate bankruptcy analogy is poor, that Europe’s interest in the development and cohesiveness of its empire would substitute for narrow economic incentives (which should in any case be blunted, since they are the incentives of 27 different fiscs). If the past five years had not happened, I might be open to the argument made here (ht platypus) that, having extended the maturity of a large quantity of debt far into the future, creditors’ position is more like equity, since the fraction of face value creditors eventually recover is dependent upon Greece’s long-term growth.

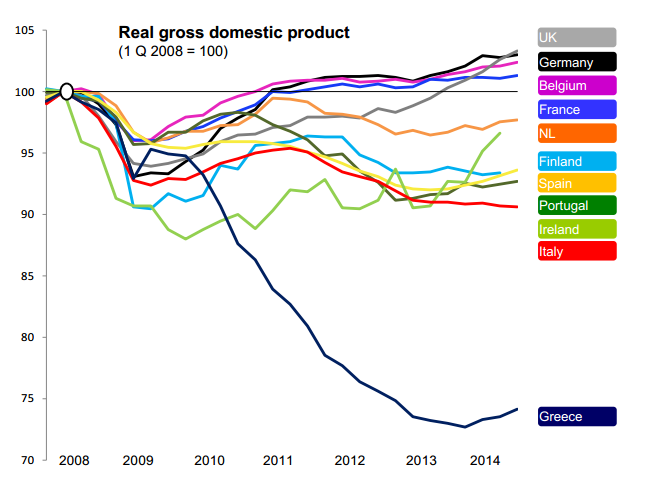

But we have had five years to observe creditors’ tender ministrations, under governments that complied with creditors’ every demand. This has been the result:

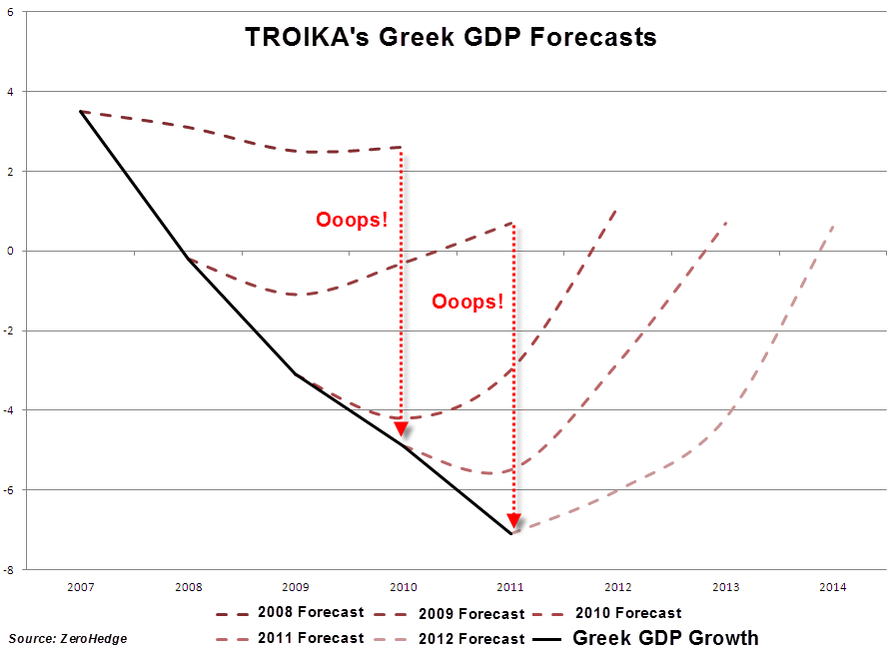

Euroelite apologists cite the small upturn at the very end of the graph to say, “See! Things were going swimmingly until the five-month old Syriza government screwed it all up. They just had to stick with the program! It was working! The darkest hour comes before the dawn!” These people, they are sophisticated highly educated people. You can trust them. Check out this track record:

The fact of the matter is no country, not Germany, not France, would voluntarily put up with the sort of “adjustment” that has been forced on Greece, for the good reason that gratuitous great depressions are not actually helpful to an economy. Creditors have had five years to mismanage Greece and they’ve done a startlingly effective job. Syriza has had five months to object. However much you may dislike their negotiating style, however little you think of their competence, Greece’s catastrophe was not Syriza’s work. If creditors respond to Syriza’s “intransigence” with maneuvers that cause yet more devastation, that will be on the creditors. Blaming victims for having insufficiently perfect leaders is standard fare for apologists of predation. Unfortunately, understanding this may be of little comfort to the disemboweled prey.

Europe’s creditors are behaving exactly as one might naively predict private creditors would behave, seeking to get as much blood from the stone as quickly as possible, indifferent to the cost in longer-term growth. And that, in fact, is a puzzle! Greece’s creditors are not nervous lenders panicked over their own financial situation, but public sector institutions representing primarily governments that are in no financial distress at all. They really shouldn’t be behaving like this.

I think the explanation is quite simple, though. Having recast a crisis caused by a combustible mix of regulatory failure and elite venality into a morality play about profligate Greeks who must be punished, Eurocrats are now engaged in what might be described as “loan-shark theater”. They are putting on a show for the electorates they inflamed in order to preserve their own prestige. The show must go on.

Throughout the crisis, European elites have faced a simple choice: Acknowledge and explain to electorates their own mistakes, which do not line up along national borders of virtue and vice, or revert to a much older playbook and manufacture scapegoats.

Such tiny, tiny people.

Update History:

- 4-Jul-2015, 11:45 a.m. EEDT: Capitalize S in “Black Sea”, “then” ⇒ “than”

- 4-Jul-2015, 7:15 p.m. EEDT: “The brought back” ⇒ “They brought back”; add apostrophe to “debtors’ prison”.