Zoning laws and property rights

A couple of weeks ago, I sat down and read Matt Yglesias’ The Rent Is Too Damned High and Ryan Avent’s The Gated City back to back. Both were a pleasure to read, for their content, and for the opportunity to kick a couple of bucks to two of my fave bloggers behind an ennobling veil of commerce. As an avid reader of both authors’ online work, there were no huge surprises, but reading the ebooks took me deeper and inspired some more considered thought on their ideas. Ryan Avent and Matt Yglesias (and Ed Glaeser too!) are separate humans with their own identities and ideas. But these “econourbanists” share a core view, and I hope they will forgive me if I consider their work together. Although they arrive at a similar place, the two books take very different roads: Avent’s book is a bit wonkier and more economistic, focusing on the macro role of cities in enhancing productivity through economies of scale and agglomeration; Yglesias treats the same set of issues more polemically and with an emphasis on the personal, thinking about how individuals should expect to make a living in an increasingly service-oriented economy, the importance of accessible cities to the kind of prosperity he envisions, and the perils of any obstacle that makes urban life inaccessible (“the rent is too damned high!”). Read both!

In a nutshell, the econourbanists’ case is pretty simple: Cities are really important, as engines of the broad economy via industrial clustering, as enablers of efficiency-enhancing specialization and trade, as sources of customers to whom each of us might sell services. Contrary to many predictions, technological change seems to be making human density more rather than less important to prosperity in the developed world. Commerce intermediated at a distance via material goods has become the province of cheap workers in distant lands, and will very soon be delegated to robots. The value of human work is increasingly in collaborative information production and direct personal services, all of which benefit from the proximity of diverse multitudes. Unfortunately, in the United States at least, actual patterns of demographic change have involved people moving away from high density, high productivity cities and towards the suburbanized sunbelt, where the weather is nice and the housing is cheap. This “moving to stagnation”, in Avent’s memorable phrase, constitutes a macroeconomic problem whose microeconomic cause can be found in regulatory barriers that keep dense and productive cities prohibitively expensive for most people to live in. It is not that people are “voting with their feet” because they dislike New York living. If people didn’t want to live in New York, housing would be cheap there. It isn’t cheap. Housing costs are stratospheric, despite the chilly winters. People are voting with their pocketbooks when they flee to the sun. (“The rent is too damned high!”) Exurban refugees would rush back, and our general prosperity would increase, if the clear demand for high-density urban living could be met with an inexpensive supply of housing and transportation. The technology to provide inexpensive, high quality urban housing is readily available. If “the market” were not frustrated by regulatory barriers and “NIMBY” politics, profit-seeking housing developers would build to sell into expensive markets, and this problem would solve itself.

Before going on, I should confess that I am not neutral. I was on-board with the econourbanists’ project before I’d read a word they’d written. I have always loved cities, and the problem at the center of Yglesias’ book has been a pressing problem in my own life. (I enjoy very dense and cosmopolitan cities, but am too risk averse to accept the steady burden of a high rent given the uncertain and irregular clumps by which I’ve earned my living.) Ultimately, I think that Avent and Yglesias and Glaeser have the right vision of the world that we need to move towards.

I’m skeptical, however, of the path that they’ve outlined to get us there. The econourbanists’ deregulatory ideas might win some victories at the margin, and might lead to important and useful reforms of regulatory “best practices”, for example regarding parking. But as a political matter, I don’t think it will be possible to diminish neighborly veto power over new development enough to put a dent in housing undersupply. As a matter of fairness, I think they underestimate the degree to which what they are after amounts to a “taking” from incumbent homeowners, not all of whom are unsympathetic rich bastards. And even if they could “win”, though it is clear that untrammeled developers would deliver housing supply, I don’t think they’ve made the case that a deregulated market would deliver high quality density. The econourbanists make a good case that density may be necessary to their vision of prosperity, but density is obviously not sufficient. The world has its Manhattans and San Franciscos, but it also has plenty of dense slums in poor cities. I’d like to see more attention to the circumstances that actually conjured the places we now recognize as dense, prosperous, and desirable. Was it the sort of libertarianism they prescribe?

One should always be careful of claims that problems could be solved if only we “let the market do its work”. I don’t mean to go all PoMo, but to the degree that there exists an institution we might refer to as “the market”, it is doing its work and it is not doing the work Ygesias and Avent ask of it. There is the market as it is, and then there is an infinite range of markets that might exist if the institutional arrangements and property rights that govern market transactions were different. Given the political obeisance still compelled in the United States by “market outcomes”, it is a common trick to claim that outcomes one would prefer are the outcomes that would occur if only institutions and property rights were redefined “appropriately”. That may be useful rhetorically, but it is always a bit disingenuous. In reality, what Yglesias and Avent propose is a redefinition of the rights surrounding urban property. If you redefine the institution of property, you reshape market outcomes. But persuading people to liberalize zoning restrictions in the name of “free markets” will be hard. Because the reform that Avent and Yglesias want — along with the developers who would love to build in expensive cities, and the people like me who would love to live in expensive cities but can’t afford to — amounts to an expropriation, a confiscation of property rights, from one of the best organized and most politically enfranchised groups in the United States.

A property right is first and foremost a right to exclude uses other than those desired by its owner. My car is mine because you can only do with it what I want, or else you can’t use it at all. When a person purchases “real estate”, they are buying a bundle of rights to exclude. You cannot trespass on my land without my permission, you can not be sheltered by my roof without my permission. But dirt and roofs are commodity items. If exclusive use of some dirt and a roof are all I am after, then, well, they are cheap in the sunbelt. If I purchase a home in an expensive city, in a “nice, stable neighborhood with good schools”, I’m paying for a lot more than dirt. Yes, I am paying for proximity to my prosperous city’s opportunities and amenities, but that is not all. I am also paying for the fact that not only my home, but my neighbor’s home, is being put to a use that pleases me and to which I would consent. I am paying for the fact that my neighbors themselves are the kind of people I would be pleased to live next door to. I’m paying for the fact that, as parents, the people whom I am moving in with send well-raised children to the local public school and devote some fraction of their attention to the management of that school. I’m paying for the fact that the streets, the architecture, the trees and public parks, are arranged in a way that pleases me. These are all reasons why, if I had the kind of money I do not have, I might pay up to live in a “nice neighborhood” located near the heart of a thriving city.

You might say this is idiotic. Narrowly, my deed to a certain property doesn’t entitle me to exclude bad parents from moving in next door or to prevent a high rise from replacing charming brownstones across my street. If the weather is nice on the day I purchase my home, does that grant me a legal right to perpetual sunshine?

But property rights arise in practice before they are written on paper. Even if they are never codified, the law, whether through courts or through legislatures, is loathe to disturb customary rights (unless the holders of evolved property belong to politically marginal classes). When people spend small fortunes on a “charming brownstone”, they do so with the understanding that the neighborhood is in fact “stable”. At some level, these affluent, educated buyers know that with their deed to the property comes an ability to exclude alternative uses of the neighborhood. That is part of what they are purchasing, a substantial part of the value for which they are laying out hundreds of thousands of dollars.

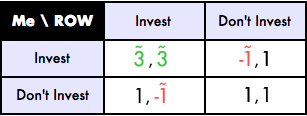

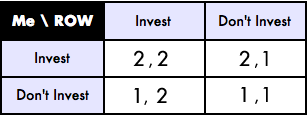

The mechanism by which that right is enforced is the thicket of zoning laws and permitting requirements that allow activist property owners exclude uses of the neighborhood to which they do not consent. It is this mechanism that invites the framing adopted by Avent, Yglesias, and Glaeser. Since the right to exclude is enforced by the operation of regulatory bureaucracies rather than by the criminal law of theft and trespass, we can claim that it is “government” that is enforcing policies whose outcomes we dislike in opposition to the “rights” of individual sellers, potential new residents, and property developers, to do as they please. But in substance, the enforcement mechanism is secondary. Purchasers of properties in “nice, stable” neighborhoods paid up for a right to exclude uses of their neighbors’ property to which they would not consent, and potential sellers who might enjoy a windfall if they could sell out to a high-rise developer understood when they purchased their properties that neighbors would likely prevent them from exploiting this sort of opportunity. Ex ante, most property owners are glad to cede the right to sell to a developer in exchange for the right to prevent their neighbors from doing the same. Retaining that right would create a prisoner’s dilemma whereby the threat of a neighbor’s defection (she sells to a developer at an attractive price for a use that impairs my property’s value) would leave each owner in a poor bargaining position, and guarantee that the character of the neighborhood could not be preserved. The value of neighborhood properties could not be justified or sustained without protection from this dynamic.

The private-property-like quality of zoning law is evident in the fact that where municipal regulations don’t enforce the right to exclude alternative uses of a neighborhood, property owners invent contractual means of doing the same. Developers, whether of high-rise condominiums or sprawled out “golf communities”, cobble together with a mix of contract and corporation law obligatory “community associations” that control and restrict the use of privately-owned properties (along with managing common spaces and other purposes). Developers don’t abridge the rights of their customers out of some inexplicable, cruel perversion. They form these associations, and grant them restrictive powers, because customers demand it, because doing so maximizes the market value of the properties they wish to sell. As buyers, developers hate zoning law, but as sellers they promulgate it. It is “the market” that demands some mechanism of overcoming potential coordination problems among neighbors, not the acommercial mix of identity politics, misplaced environmentalism, and “NIMBY”-ism that Yglesias and Avent emphasize. The only reason city neighborhoods don’t have restrictive covenants and powerful community associations is because they have city governments that serve the same function.

The definition of and proper scope of property rights is always contestable. As a matter of sheer interest politics — both my interest in finding an affordable home in a great city, and my interest in a productive and vibrant macroeconomy — I want to be on-board with Avent and Yglesias, and simply argue that the historical ability of urban property owners to exclude undesired development should not be construed as a property right. There are lots of purported property rights that I consider illegitimate and am perfectly willing to contest. For example, I agree enthusiastically with Yglesias that we have overextended rights to exclude on a variety of issues: so-called “intellectual property”, immigration law, and occupational licensing. All of these controversies pit the short-to-medium term interests of organized incumbents against those of unseen and less organized new entrants, and arguably against the long-term interests of the polity as a whole. But I am a bit more hesitant on the zoning question.

If we reform away urban zoning restrictions, are we going to invalidate the restrictive covenants of suburban developments? Affluent urban property owners would have almost certainly evolved institutions that perform the functions of community associations if they were not able to rely upon the good offices of municipal government for the same. If restrictions on higher-density development are illegitimate, then should the state refuse to enforce such restrictions when they are embedded in private contracts? Perhaps the answer is an enthuastic “Yes!” After all, over the last 60 years, the state intervened very nobly to eliminate a “property right” enshrined in restrictive covenants and designed to exclude people of certain races from their neighborhoods. Three-thousand cheers for that! But state refusal to enforce previously legal contracts sounds a lot less like “letting the market work” and a lot more like deliberate government action. It would be short-sighted to reform away municipal residents’ ability to exclude commercial and high-density development while leaving contractual restrictions negotiated between property owners enforceable. That would create a window for some high-density development against the wishes of affluent incumbents, but over time the result would be the privatization of affluent neighborhoods. Property owners would form restrictive community associations and purchase potential development sites as common property. There is already a de facto stratification of tacit property rights within cities. Very affluent communities have nearly automatic veto power over unwanted development while poorer homeowners sometime fight very hard to preserve the status quo. A regime that liberalized zoning restrictions without invalidating contractual restrictions would increase this block-level stratification, and perhaps move us from “gated cities” to a brave new world of gated neighborhoods.

I feel like a sourpuss in all of this, or at best a devil’s advocate. I like Matt Yglesias and Ryan Avent very much. I’m an ardent fan of their work, and I’m likely to be on their side in most actual controversies. I’ll enthusiastically support public or private action that promotes dense urban growth and transit-oriented development. But I think that’s going to require deliberate action, public and private, not just “getting government out of the way” and letting markets work. Dense cities exist to generate economies of scale. But markets cannot be relied upon to discover and exploit economies of scale “on their own”. Capturing economies of scale requires a leap across a chasm, the allocation of resources away from uses that are plainly productive towards uses that seem at first to be less valuable. The eventual benefits start off uncertain and hypothetical, so capturing economies of scale requires that someone bear very large risks of failure. Usually this requires coordination among many actors to divide costs and benefits. The econourbanists’ deregulatory scheme amounts to funding the initial costs of densification with value expropriated from incumbent homeowners, who are asked to cede the status quo pleasantness and exclusivity of their neighborhoods in the service of a hypothetical long-term abundance. That doesn’t strike me as a particularly fair way to finance what I agree is a very worthy project. Given the disproportionate political power of incumbent homeowners, it doesn’t strike me as a tactic very likely to succeed.

Update: I was flipping through The Rent Is Too High this afternoon (3/29), and noticed that Yglesias makes the very same connection that I felt very clever to make in this post, that zoning laws are really a form of property right. Yglesias writes

One way to think about the story I’ve been telling here is as a tale of big government run amok, an out-of-control abridgment of private property rights. A better way to think about it is that over the past several decades, there’s been a revolution in our understanding of what property rights entail. We’ve switched from a system in which owning a piece of real estate means you’re entitled to do what you want with it, to one in which owning a piece of real estate means you get wide-ranging powers to veto activities on your neighbors’ land.

Yglesias supports undoing zoning restrictions despite their property-like character.

He has my apologies for not acknowledging his description of zoning laws as an extension of property. I wrote this post several weeks after reading his book, and have made an unintentional plagiarist of myself by not recalling that he made this point.

Update History:

- 26-Mar-2012, 1:10 a.m. EDT: “a “nice neighborhood”

convenientlylocated near the heart of a thriving city.”; “cobble together with a mix of contract and corporation law obligatoryand perpetual‘community associations’ “; “Usuallythatthis requires coordination among many actors to divide costs and benefits.” - 30-Mar-2012, 1:10 a.m. CDT: Added bold update re Yglesias’ prior characterization of zoning restrictions as property rights.