Restraining unit labor costs is a right-wing conspiracy

In an otherwise excellent post, Matt Yglesias commits one of the deadly sins of monetary policy:

[M]y favorite indicator of inflation is “unit labor costs”… Unit labor costs are basically wages divided [by] productivity. It’s not the price of labor, in other words, but the price of labor output. If productivity is rising faster than wages, then even if wages themselves are rising unit labor costs are falling. Conversely, if wages rise faster than prodictivity than unit labor costs are going up. Clearly there’s nothing wrong with a little increase in unit labor costs here or there. But over the long term, growth in unit labor costs needs to be constrained or else it becomes impossible to employ anyone. And you can see that in the seventies it’s not just that gasoline got more expensive, we had an anomalous spate of high unit labor cost growth. That was inflation and it’s what led to the regime change that’s governed for the past thirty years.

That all sounds reasonable. But Yglesias has fallen into a trap. Unit labor costs are not “basically wages divided [by] productivity”. That’s not the right definition at all. [See update below.] Unit labor costs are nominal wages per unit of output. With a little bit of math [1], it’s easy to show that

An increase in unit labor costs can mean one of two things. It can reflect an increase in the price level — inflation — or it can reflect an increase in labor’s share of output. The Federal Reserve is properly in the business of restraining the price level. It has no business whatsoever tilting the scales in the division of income between labor and capital.

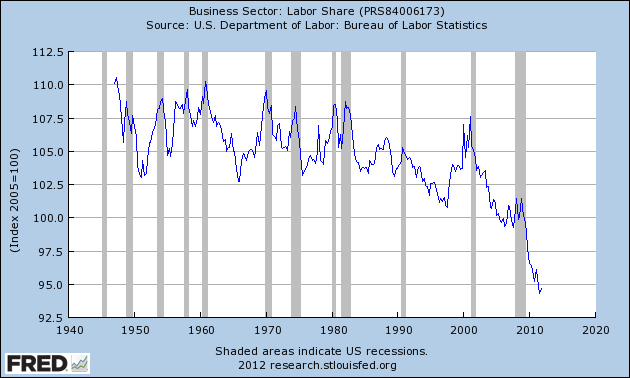

Yet throughout the Great Moderation, increases in unit labor costs were the standard alarm bell cited by Fed policy makers as an event that would call for more restrictive policy. And all through the Great Moderation, except for a brief surge during the tech boom, labor’s share of output was in secular decline. (More recently, the Great Recession has been accompanied by a stunning collapse in labor share. Record corporate profits!)

Correlation is not causation, and undoubtedly much of the decline in labor share can be attributed to factors unrelated to monetary policy, such as the integration of China into global labor markets. But even if the Fed didn’t “cause” the decline in labor’s share, Great Moderation monetary policy made it very difficult for labor’s share to grow. Consider a simple rearrangement of the equation above:

For labor’s share to expand, either the price level must fall, or unit labor costs must rise faster than the price level. But the Fed responds aggressively to rising unit labor costs, and is committed to preventing any decrease in the price level. Under this policy regime, expansions in labor’s share are pretty difficult to come by! There was that late 1990s surge in labor’s share. But that is the exception that proves the rule: The Fed, to its credit, tolerated an expansion in unit labor costs from 1997 through 1999 without raising interest rates.

In addition to its direct suppression of labor’s share of output, the Fed’s hawkish rhetorical hawkishness on unit labor costs had debilitating indirect effects. Politicians view contractionary monetary policy as a threat to reelection. George H.W. Bush famously blamed the Greenspan Fed for not easing sufficiently prior to his failed reelection bid. Bill Clinton famously chose Rubinomics over, say, Reichonomics, and he cultivated a cordial detente with the Fed. Far too much attention is given to keeping central banks independent of politicians, and far too little is given to keeping politicians independent of central banks.

Since the early 1990s, all actors in the US political system have understood that policies that increase unit labor costs risk a response by the “inflation fighting” central bank, whose “credibility” was swaggeringly defined as a willingness to provoke recession rather than risk inflation. In this environment, the decline of labor unions and their shift in focus from wage growth to working conditions was understandable. If workers won on wages, they would lose when the recession put them out of work. As long as wages were contained, monetary policy was “accommodative”, and workers could supplement their purchasing power with borrowings and asset appreciation. During the Great Moderation, wage growth was rendered obsolete. A superior means of middle class prosperity had been invented. Or so it seemed, until we experienced the toxic after-effects in 2008. Now we have grown skeptical of debt-fueled pseudoprosperity. But the covert hostility to wage growth that underpinned Great Moderation monetary policy remains unchallenged.

I imagine some readers saying to themselves, “But still. If the labor cost of ‘stuff’ is allowed to grow, how can that not be inflationary? It’s common sense.” And that’s true, as far as it goes. But if the capital cost of stuff grows, that must also be inflationary. Suppose we define the complement to unit labor costs, unit capital costs. Unit capital costs might be defined as “business profits per unit of output”. Would it be politically tolerable in the United States to have a central bank that prevented expansions of business profit per unit sold? Is restraining profitability of investment a proper role for a central bank? If suppressing returns to capital would be improper, why on Earth do we tolerate a central bank that opposes returns to labor?

There is an orthodox answer to this question. Wages, it is said, are sticky, while returns to capital are highly flexible. Elevated wage levels distort the economy, or force us to tolerate inflation in order to reduce real wages. Capital prices respond to market forces and find their efficient level. That might all be true at a micro level, but at a macro level our experience is opposite. The fraction of expenditures we pay into corporate profits has ratcheted upward pretty continuously since the mid-1980s, with a brief lull in the late 1990s and an even briefer one during the Great Recession. The share we pay as wages has fallen precipitously. In aggregate, labor has proven very flexible in its demands while the rentier class has been quite rigid. Economists like to be microfounded and all, but this is macroeconomics, and actual macroeconomic evidence has to count for something.

All of this is one more reason to prefer the NGDP path target promoted by Scott Sumner and his merry Market Monetarists. It might prove difficult in practice to target inflation without paying some especial attention to wage growth. But a central bank can target the path of aggregate expenditure without playing favorites about who pays what to whom. Simple neutrality by the central bank in the contest between capital and labor would be a huge improvement over the status quo.

Many thanks to Nick Rowe, who probably doesn’t agree with any of this, but helped me think these issues out in the comments here.

Update: It is easy to show that unit labor costs are not equal to total wages divided by labor productivity. But Nick Rowe points out in the comments that unit labor costs are equal to the average hourly wage divided by labor productivity. So, depending on how you want to interpret “wages”, I was too quick in tweaking Matt Yglesias for a misstatement. Sorry!

Thanks to Rowe, Dan Kervick, and JKH who work this out carefully in the (excellent) comment thread.

[1] Here’s the math. By definition…

UNIT_LABOR_COSTS = (NOMINAL_WAGES_PAID / TOTAL_NOMINAL_EXPENDITURES) (TOTAL_NOMINAL_EXPENDITURES / QUANTITY_OF_REAL_OUTPUT)

But (NOMINAL_WAGES_PAID / TOTAL_NOMINAL_EXPENDITURES) is just labor’s share of GDP and (TOTAL_NOMINAL_EXPENDITURES / QUANTITY_OF_REAL_OUTPUT) is the price per unit of output, or the price level. So we have…

Update History:

- 22-Feb-2012, 12:30 a.m. EST: Added update re alternative definition of “wages divided by productivity”. Added “[by]” where quote read “wages divided productivity”.

By what mechanism does the Fed’s policy actually alter the division of output between capital and labor? You say:

For labor’s share to expand, either the price level must fall, or unit labor costs must rise faster than the price level.

Well, when the Fed tightens don’t we generally infer that it reduces unit labor costs precisely by causing the price level to fall (or to rise more slowly)? You have to explain that the Fed somehow restraints unit labor costs without affecting the price level path. How?

February 21st, 2012 at 3:27 am PST

link

Alex — I don’t claim that the Fed somehow surgically suppresses labor share without restraining the price level. They oppose unit labor cost expansion. Their actions are likely to affect both components, and, in the absence of deflation, are sufficient to prevent any expansion of labor share (as long as the Fed succeeds at preventing unit labor costs from growing faster than inflation).

February 21st, 2012 at 3:54 am PST

link

I don’t think that addresses the point, though. My naive assumption would be that the Fed’s policies only directly affect one component – the price level – and only have an indirect effect, if any, on real unit labor costs. We generally talk about the Fed policy as a one-dimensional lever – it can be tightened or loosened – and your thesis seems to be that by tightening at specific times and loosening at others, the Fed influences the long-term division of output between capital and labor.

If the Fed had adopted the reverse policy, where it retained the same target but used rising capital costs as its inflation early-warning system, do you think the opposite result would have obtained?

February 21st, 2012 at 4:22 am PST

link

Alex — Sure. In a counterfactual history in which the Fed made it very clear that it would not permit business profits to rise on a per unit basis faster than its price level target, and where it gained credibility by raising rates and slowing the economy, even risking recession, when “unit profits” rose, I think you’d see firms distribute their income much more in the form of wages, and you’d have seen much more moderate asset price growth than we’ve seen.

You might argue that this would just be a kind of arbitrage, and somehow the same stakeholders would take their rents out as wages rather than profits, but I think that’s an overly deterministic view. When there is a surplus to be distributed within a firm, broad coalitions of employees within firms have historically succeeded to get a share. (Indeed, the decline of unions is often blamed on competition creating a situation in which there is nothing to fight for. But what is now distributed as return on capital would be something to fight for.) Further, it’s much harder for wealthy people to arrange to collect labor income from multiple enterprises if the formal returns are very low. You can imagine some schemes: Mr. Moneybags provides cheap financing, and gets put on the payroll for a sham job. But that’s lots harder than buying shares in a rising stock market, and hard to diversify over many firms. Overall, wage earners generally would be in a better position to bargain for income than in the current world where the capitalist wants an exit and the overall regulatory and political environment facilitates firms giving him one.

That said, I don’t know the magnitudes. I don’t think anyone does, and attempts to estimate would be very contestable. Globalization, communications, and cheap transport have certainly created “real” headwinds for labor bargaining power. Labor is not as scarce a factor as it once was. But then, for much of the decade preceding 2008, we had a “global savings glut”. In the US, capital was not at all a scarce factor, Wall Street was cheating to invent means of deploying it. That should would have militated towards to an increase in labor share, but we certainly didn’t see that. Regardless, maybe the “real” forces pushing down labor share would have won regardless, maybe not. But at the margin, however great or small the effect, Great Moderation monetary policy did harm labor bargaining power. It was not neutral, and it was not helpful.

February 21st, 2012 at 4:50 am PST

link

[…] interfluidity » Restraining unit labor costs is a right-wing conspiracy […]

February 21st, 2012 at 8:25 am PST

link

SRW,

You note the change in unit labor cost.

What about aggregate labor cost, and the dominance of the aggregate labor cost share of the macro total, as an impinging factor in the policy management of unit labor costs?

Aggregate labor costs remain disproportionate to aggregate capital costs, notwithstanding the relative deflation in unit labor costs.

In the management of pass-through inflation risk, is unit labor cost an innocent bystander in a bigger game of attempting balance of risk in aggregation?

In other words, are the aggregate risk shares such that unit labor cost policy management is skewed to risk of less rather than risk of more, in terms of management of total inflation risk exposure?

(If so, that certainly hasn’t helped in the current deflationary environment, where deflation risk has been underestimated, whatever its source.)

Quick reaction – not sure if this makes any sense.

February 21st, 2012 at 10:38 am PST

link

Yes, in my opinion, monetary policy (the setting of short term risk free interest rates) had almost nothing to do with the decline in labor’s share of the pie. You raise an important question, but once again the fixation on the Fed as the Wizard of Oz leads us into the weeds…

February 21st, 2012 at 11:35 am PST

link

Great post.

And if you read stuff like this, or Greider’s Secrets of the Temple, it’s very clear that restraining the labor share has been a major objective for decision makers at the Fed, regardless of their statutory mandate.

February 21st, 2012 at 2:49 pm PST

link

Interest rates have fallen steadily and steeply during the period under discussion, while interest rate sensitive sectors of the economy (e.g. housing, auto) boomed. Is anyone arguing that all would be well if the Fed would have just lowered interest rates more / faster?

February 21st, 2012 at 2:50 pm PST

link

Having said that, I agree that Yglesias is off base. I’ve quit paying attention to him…

February 21st, 2012 at 3:15 pm PST

link

Dan,

Depends on which period is under discussion. A lot of the decline in labor share took place in 1980-1995, when interest rates were not low.

February 21st, 2012 at 4:32 pm PST

link

Is “Secrets of the Temple” any good? I’ve never been able to pin him down on the crank index.

February 21st, 2012 at 5:17 pm PST

link

JW– Interest rates plummeted after 1980 and continued the downtrend through 1995 and beyond — http://www.project.org/images/graphs/Prime_Rate_1.jpg…

February 21st, 2012 at 5:47 pm PST

link

Oops bad link on my graph of interest rates in previous post. Let’s try this one: http://static.seekingalpha.com/uploads/2010/1/4/saupload_historical_interest_rates.JPG

February 21st, 2012 at 5:49 pm PST

link

Responding more to your comments over at Nick’s place, and to your FRED graph:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=3BD

(JKH, does this graph speak to your aggregate labor cost issue?)

It became apparent to me quite a while ago:

Recessions are nature’s way of keeping the little guy down.

Replace “nature” with your choice of the Fed, creditors, capitalism, or just go generic: da man.

Sorry, gone full metal marxist along with Steve.

February 21st, 2012 at 5:52 pm PST

link

Steve; Thanks for the link. You are right that I don’t agree!

1. This was the first comment on my post, by Bob Murphy: “This is why you should support a gold standard. Stick it to the mine owners!” (Bob was being ironic).

2. There is, or ought be, a symmetry to monetary policy. For example, if the target is 2% CPI inflation, then the central bank should try to prevent inflation that is both higher and lower than 2%. So if you argue that the Fed was trying to prevent labour’s share rising, you should also be arguing that it was trying to stop labour’s share falling.

3. Unit_labour_cost = price_level x labour’s_share_of_output = Px(WL/PY) = WL/Y = W/(Y/L) = W/labour_productivity. Matt Yglesias was right when he said that unit labour costs are wages divided by productivity. What MattY said, and what you said, are the same.

February 21st, 2012 at 6:45 pm PST

link

There is, or ought be, a symmetry to monetary policy. For example, if the target is 2% CPI inflation, then the central bank should try to prevent inflation that is both higher and lower than 2%. So if you argue that the Fed was trying to prevent labour’s share rising, you should also be arguing that it was trying to stop labour’s share falling.

I note that in the first sentence we are presented with a choice of is and ought, but the second sentence is simply declarative. So the “so” doesn’t follow. We may perfectly well think that the Fed *ought* to have a symmetric target, but that it *actually does* act to prevent a rising labor share but not a falling one.

February 21st, 2012 at 6:55 pm PST

link

(or rather the first two sentences vs. the third.)

February 21st, 2012 at 6:56 pm PST

link

Steve Roth,

I’m not a student of that statistic.

The level surprises me (how low it is).

So the proportionate secular move is larger than I expected.

February 21st, 2012 at 7:50 pm PST

link

Simplified,

Why is an increase in labor’s share of output cost inflationary, and an increase in capital’s share of output cost deflationary?

In both cases, the sum of the two income shares buys the total output.

Why the difference in overall pricing pressure because of cost share mix?

February 21st, 2012 at 8:21 pm PST

link

@JKH: “Why is an increase in labor’s share of output cost inflationary, and an increase in capital’s share of output cost deflationary?”

Not sure if the math works, but my intuitive answer is:

1. There are few “capitals” and many “labors” (think: creditors and debtors)

2. Labors have a (much) higher marginal propensity to consume than capitals

So if you shift income to labors, spending jumps: more of them X higher MPC each. Higher velocity, more demand for real goods, prices go up.

The log rolls faster (and gets bigger?).

February 21st, 2012 at 9:08 pm PST

link

BTW, I pulled the numbers on wages vs assets share of income a while back, even dug into the old scanned IRS PDFs for pre-1929 data. Seems pretty eye-opening to me:

http://www.asymptosis.com/robert-livingston-once-again-sheds-serious-light-on-our-current-situation-as-illuminated-by-the-great-depressioncondensed.html

February 21st, 2012 at 9:16 pm PST

link

Steve Roth,

What I’m thinking is that all of the graphs, equations, etc. referenced in this post are applicable in an ex post sense when measuring the results of the economy. In that sense, all income is “spent” on real output, regardless of the labor/capital composition of that income. And also in that sense, the “veil of financial intermediation” doesn’t change the fact that the equation is satisfied at all times. All output generates all income, and all income is spent on all output, where “all” means the aggregate output and aggregate income result that is measured in the accounts.

The marginal propensity to consume doesn’t change the fact of that equation. The mix of consumption and investment along with government spending and net exports may be changing, but I’m not how or whether that correlates with a secular change in the distribution of income between labor and capital. And I’m not sure how any of this would affect the expected inflation result, given that inflation in the cost of capital infrastructure and equipment would presumably also be passed through in part to the price of consumer goods and services through the corresponding inflation of higher annual capital depreciation charges. I suspect the answer to all this is hopelessly complex, and right now I don’t have a clue.

P.S. thanks for additional info

February 21st, 2012 at 9:34 pm PST

link

I’m having trouble following Nick’s algebra only because I’m not familiar with the usual meanings of the variables. But if

1. Unit Labor Costs = Nominal Wages Paid/Real Output

and

2. Productivity = Real Output/Total Employment

then it follows that

3. Unit Labor Costs = Nominal Wages Paid/(Productivity * Total Employment)

which is not the same as Matt Y’s

4. Unit Labor Costs = Nominal Wages Paid/Productivity

So Matt’s inference – that if nominal wages paid are rising faster than productivity, then unit labor costs are going up – would appear to be fallacious. If total employment is rising along with productivity, then unit labor costs could be decreasing even if nominal wages paid are rising faster than productivity.

This could happen. In an environment with low labor bargaining power, increasingly productive workers might do a lot more work to generate substantially higher output for only somewhat higher nominal wages, so the unit labor cost goes down.

That’s the expansion phase. More realistically for the contraction phase, and again with low labor bargaining power, higher unemployment might be accompanied by higher productivity, so that the denominator of statement 3 stays constant while both nominal wages and unit labor costs decline.

February 21st, 2012 at 9:57 pm PST

link

“Why is an increase in labor’s share of output cost inflationary, and an increase in capital’s share of output cost deflationary?”

Because labor costs are mostly variable while capital costs are mostly fixed.

But this only tells you why increases in *nominal* wages are more likely to be passed through to inflation. Insofar as nominal wage increases translate into real wage increases, they aren’t, as SRW says, properly part of the Fed’s remit. (Not that the Fed necessarily agrees with us about its remit.) But the focus on wage costs as a driver fr inflation is not without its logic.

February 21st, 2012 at 10:08 pm PST

link

Dan K.

Not sure, but try this:

Starting at your # 3:

Unit Labor Costs = Aggregate Nominal Wages paid / (Productivity * Total Employment)

Aggregate Nominal Wages paid = labour wage * Total Employment

Unit Labor costs = labour wage / productivity

February 21st, 2012 at 10:37 pm PST

link

JKH,

OK, I see. I assume SRW mans the same thing by “nominal wages paid” that you mean by “aggregate nominal wages paid.

But by “wages” Matt Y. might have meant “wage per unit of employment”. So then he and SRW are both right, and are just using “wages” in a different way.

February 21st, 2012 at 10:56 pm PST

link

“Because labor costs are mostly variable while capital costs are mostly fixed.”

Capital costs are not fixed in a dynamic macro economy. Capital stock is constantly being renewed, the size of the outstanding stock is constantly fluctuating, and its financial cost is constantly changing in accordance with interest rates and risk premia.

February 21st, 2012 at 11:03 pm PST

link

Dan: “But by “wages” Matt Y. might have meant “wage per unit of employment”. So then he and SRW are both right, and are just using “wages” in a different way.”

That’s my interpretation too.

Normal conventions: W = wage per person-hour, L = number of person hours per year (employment), so WL is total wages paid per year.

February 21st, 2012 at 11:23 pm PST

link

JKH-

Maybe, maybe not. But if the question is, Why are wage cost increases *conventionally assumed* to be inflationary while capital costs increase are assumed not to be, then my answer is the right one.

February 21st, 2012 at 11:32 pm PST

link

Nick, Dan, & JKH — You guys have figured me out.

I had proven to myself that unit labor costs were not the same as TOTAL_WAGES / LABOR_PRODUCTIVITY, as Dan has done. But I hadn’t considered the interpretation of HOURLY_WAGE / LABOR_PRODUCTIVITY. It’s easy, as both Nick and JKH have done, to show that UNIT_LABOR_COST = HOURLY_WAGE / LABOR_PRODUCTIVITY. Thanks for pointing this out! I’ve added an update to the post.

February 22nd, 2012 at 1:40 am PST

link

JKH

it’s true that the overall all income=all spending. I’d argue that what matters is the velocity though.

Capital spending (and thus velocity) is lower than labour one. Higher labout spending “velocity” should generate more marginal income to labour, generating more spending. Total spending = output * price levels. Higher labour spending thus can be reflected as higher price levels, or higher output (and of course a mix of both). I’d argue the split between those two depends on the split of the income, as capital tends to increase productivity more than labour (thus more likely to improve output while keeping the price the same/lower).

If that is correct, it would mean that shift in income to labour is inflationary, shift to capital is deflationary. I don’t think though it’s so easy as this, as taken into either extreme (all income to labour/vs all income to capital), this is deflationary (although for different reasons).

February 22nd, 2012 at 4:53 am PST

link

[…] this post then go read Steve Waldmans post on unit labor costs, and tell me who has a more accurate reading of the […]

February 22nd, 2012 at 8:29 am PST

link

[…] Waldman points out it’s really hard for workers to make more money when the fed is leaning against them getti…higher wages constantly. This conservative slant is so pronounced even Mr. Super Smart liberal Matt […]

February 22nd, 2012 at 10:05 am PST

link

@JKH:

If labors get a larger proportion of Y in this period, Y could be higher next period? (Compared to the counterfactual.)

February 22nd, 2012 at 11:11 am PST

link

“The Federal Reserve is properly in the business of restraining the price level. It has no business whatsoever tilting the scales in the division of income between labor and capital.”

Actually, nominal wage targeting is a very sensible policy, perhaps even better than NGDP targeting. It was advocated by George Selgin (“Less than Zero”) as a way of implementing the “productivity norm”, and Scott Sumner also advocates it, while recognizing its political challenges.

Note that nominal wage targeting is not “unfair” to workers in expectation: the Fed will tighten if average wages rise, but they will ease if average wages fall. This may be in workers’ long-term interest, by keeping their nominal incomes stable to the greatest possible extent.

February 22nd, 2012 at 7:52 pm PST

link

‘Since the early 1990s, all actors in the US political system have understood that policies that increase unit labor costs risk a response by the “inflation fighting” central bank, whose “credibility” was swaggeringly defined as a willingness to provoke recession rather than risk inflation.’

An inflation-targeting central bank will only “provoke a recession”, properly understood (reduce NGDP growth) if a negative productivity shock hits the economy. This arguably incents politicians to pursue good supply-side policies, by rewarding them with a short-term expansion; perhaps this is what happened in the late 90s and early 2000s. The changes in labor share might have been coincidental. Of course, this policy showed its negative side after the energy price shock led to a productivity decline.

Your criticism seems to apply to nominal wage targeting, except that the magnitude of changes involved is implausible, at least in the short term which is where monetary policy actually matters. Though expectational effects may change this prediction: if unionization is expected to greatly increase the wage share in the future, then we’re going to have a recession now as the policy response is foreseen. Perhaps Nick Rowe or Scott Sumner can weigh in on this.

February 22nd, 2012 at 8:11 pm PST

link

It feels wrong to cite Peter Orszag as an authority on anything, but he made a good point—

“In Economics 101, students learn that the share of national income received by labor stays roughly constant with the share received by capital. This is the first of “Kaldor’s stylized facts,” articulated half a century ago by the Cambridge economist Nicholas Kaldor.

Recent experience betrays this lesson. Over the past two decades — and especially since about 2000 — the share of national income that flows into wages and other kinds of worker compensation has been plummeting…

The difference from 1990 to today — about 5 percentage points or so of private-sector income — amounts to more than $500 billion a year. In other words, if labor’s share hadn’t fallen, labor income would be $500 billion higher this year.”

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-10-19/kaldor-s-facts-fall-occupy-wall-street-rises-commentary-by-peter-orszag.html

February 22nd, 2012 at 11:46 pm PST

link

[…] interfluidity » Restraining unit labor costs is a right-wing conspiracy […]

February 23rd, 2012 at 1:32 am PST

link

I don’t know in the US but in Europe, restraining ULCs is the obssesion of central bankers. How does Germany, as a country, manage to cut ULCs? One way to do that is promote investments in capital intensive industries and rely heavily on exports. For a big and economically diversified country as the US talking about ULCs may have sense or not but in the case of Europe, when policymakers are obsessed with “Competitivity” and ULCs the comparisons between european countries are more or less pointless since different countries more or less specialise in different outputs: you end comparing apples with oranges. Focusing on ULCs may not only be a way to diminish the share of labour in output, but also a way to avoid talking about the real financial imbalances that are the root of current account imbalances among eurozone countries.

We need less talk about competitivity an much more on finantial regulation.

February 23rd, 2012 at 4:52 am PST

link

i like your post but i cant help to say that you need to see this http://imn4.info your site is like missing something , take a look you will not regret it thank me later

February 23rd, 2012 at 10:21 am PST

link

@ 38 Beowulf, during the 2008 campaign, Obama himself said in an interview with BusinessWeek that since the 90s wages haven’t kept up with productivity gains; that it isn’t fair and government could balance the playing field.

@ 36 “This may be in workers’ long-term interest, by keeping their nominal incomes stable to the greatest possible extent.”

It’s better than what’s been happening which is “opportunistic disinflation” at the expense of workers and for the benefit of rentier class.

February 23rd, 2012 at 6:40 pm PST

link

“For labor’s share to expand, either the price level must fall, or unit labor costs must rise faster than the price level. But the Fed responds aggressively to rising unit labor costs, and is committed to preventing any decrease in the price level.”

It is interesting that when people discuss deflation, it is always with the perspective of “assets” – no one much worries about wage “deflation” – indeed, the term is never used when discussing wages. But TARP and all of the powers of the government are used to prevent asset prices from falling…

“But if the capital cost of stuff grows, that must also be inflationary. Suppose we define the complement to unit labor costs, unit capital costs. Unit capital costs might be defined as “business profits per unit of output”. Would it be politically tolerable in the United States to have a central bank that prevented expansions of business profit per unit sold? Is restraining profitability of investment a proper role for a central bank? If suppressing returns to capital would be improper, why on Earth do we tolerate a central bank that opposes returns to labor?”

Excellent questions and why indeed. Is it because people had 401k’s and people were willing (or more likely, had to) to accept lower compensation for high growth in their retirement accounts? Or people used available credit to buy houses in a desperate attempt to stay even?

I’ve always thought it inconsistent that the stock market or houses increasing in prices is not typically considered inflationary, or a problem, but any increase in wages is (in both cases the price increases are above objective criteria of assessment e.g., the stock market gains far exceeding GDP plus inflation increases). Funny how that works

February 24th, 2012 at 7:55 am PST

link

Here’s the math. By definition…

UNIT_LABOR_COSTS = NOMINAL_WAGES_PAID / QUANTITY_OF_REAL_OUTPUT

UNIT_LABOR_COSTS = (NOMINAL_WAGES_PAID / TOTAL_NOMINAL_EXPENDITURES) (TOTAL_NOMINAL_EXPENDITURES / QUANTITY_OF_REAL_OUTPUT)

But (NOMINAL_WAGES_PAID / TOTAL_NOMINAL_EXPENDITURES) is just labor’s share of GDP and (TOTAL_NOMINAL_EXPENDITURES / QUANTITY_OF_REAL_OUTPUT) is the price per unit of output, or the price level. So we have…

UNIT_LABOR_COSTS = LABOR_SHARE_OF_OUTPUT × PRICE_LEVEL

Being unformed, as well as not too bright, why exactly do economists in their equations mix “real” and “nominal”??? Is there a reason it can’t be done with real wages and real output???

seems kind of apples and orangy

February 24th, 2012 at 8:02 am PST

link

[…] justifying labor-hostile monetary policy, unit labor costs are often trotted out to blame unreasonable wage expectations for troubled […]

February 25th, 2012 at 6:01 pm PST

link

[…] Restraining unit labor costs is a right – via wing conspiracy – An increase in unit labor costs can mean one of two things. It can reflect an increase in the price level — inflation — or it can reflect an increase in labor’s share of output. The Federal Reserve is properly in the business of restraining the price level. It has no business whatsoever tilting the scales in the division of income between labor and capital.Yet throughout the Great Moderation, increases in unit labor costs were the standard alarm bell cited by Fed policy makers as an event that would call for more restrictive policy. And all through the Great Moderation, except for a brief surge during the tech boom, labor’s share of output was in secular decline. (More recently, the Great Recession has been accompanied by a stunning collapse in labor share. Record corporate profits!) […]

February 27th, 2012 at 12:51 am PST

link