A different perspective on interest rates

In the endless debates over stimulus and deficits, more “dovish” commentators frequently point out that debt markets appear sanguine about US borrowing. Despite some recent upward jitters, the Federal Government currently pays less than 4% to borrow for 10 years, and under 5% to borrow for 30 years. Those are bargain rates in historical terms, the argument goes, so investors must not be terribly concerned about inflation or default or any other bogeyman of “deficit terrorists”.

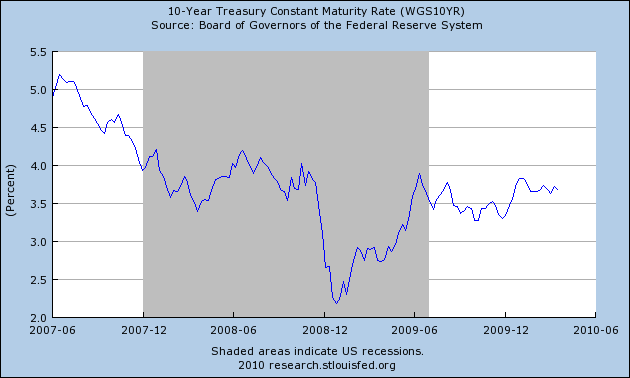

To make the point, Paul Krugman recently published a graph very similar to this one:

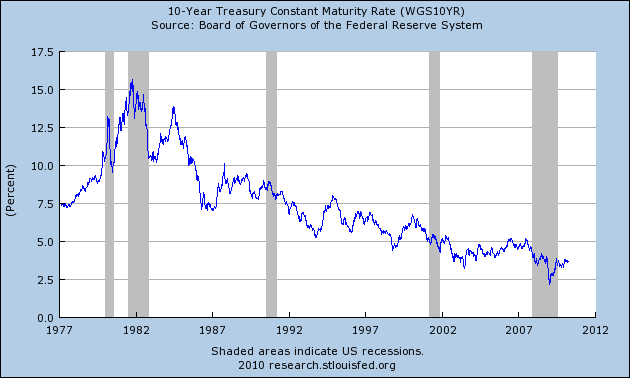

Since the financial crisis began, the US government’s cost of long-term borrowing has dramatically fallen, not risen. If we graph a longer series of 10-year Treasury yields, the case looks even more compelling. The United States government can borrow very, very cheaply relative to its historical experience.

However, there is another way to think about those rates. The US government’s cost of long-term borrowing can be decomposed into a short-term rate plus a term premium which investors demand to cover the interest-rate and inflation risks of holding long-term bonds. The short-term rate is substantially a function of monetary policy: the Federal Reserve sets an overnight rate that very short-term Treasury rates must generally follow. Since the Federal Reserve has reduced its policy rate to historic lows, the short-term anchor of Treasury borrowing costs has mechanically fallen. But this drop is a function of monetary policy only. It tells us nothing about the market’s concern or lack thereof with the risks of holding Treasuries.

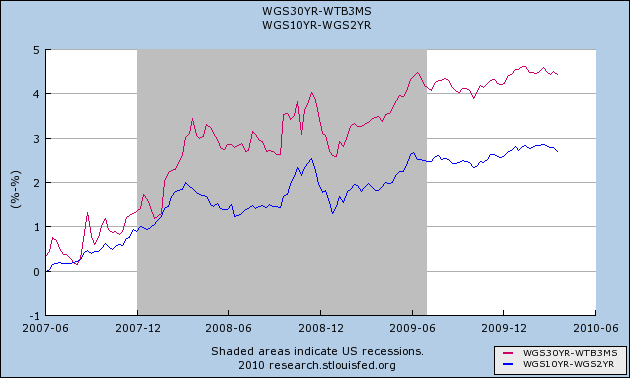

But the term premium (or “steepness of the yield curve”) is a market outcome (except while the Fed is engaged in “quantitative easing”). How do things look when we graph the term premium since the crisis began?

The graph below shows the conventional barometer of the term premium, the 2-year / 10-year spread (blue), and a longer measure, the spread between the yield on 3-month T-bills and 30-year Treasury bonds (red), since the beginning of the financial crisis:

Since the financial crisis began, the market determined part of the Treasury’s cost of borrowing has steadily risen, except for a brief, sharp flight to safety around the fall of 2008. Investors have been demanding greater compensation for bearing interest rate and inflation risk, but that has been masked by the monetary-policy induced drop in short-term rates.

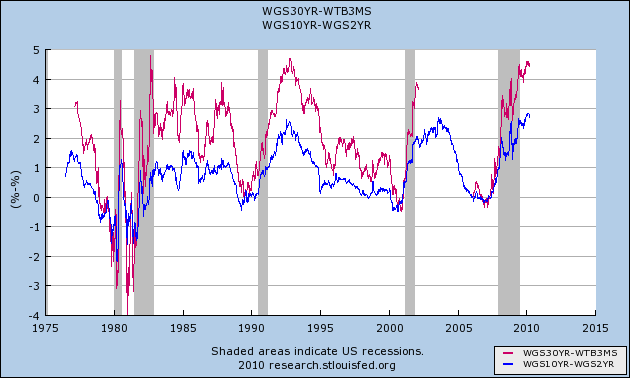

Taking a longer view, we can see that the current term premium is at, but has not exceeded, a historical extreme:

Note: There’s a gap in the 30-year rate series, probably because it became impossible to compute a “constant maturity” 30-year Treasury yield during the period when the Treasury stopped issuing 30-year bonds.

The present term premium is quite similar to those that vexed President Clinton during the heyday of the “bond vigilantes”. A glass half full story says that, despite all the stresses of the financial crisis and the sharp spike in Treasury issuance, the term premium has not become unmoored from its historical range. A glass half empty story says that the term premium is toying with the boundary of that range, and could break loose in an instant. I have no idea which tale is truer.

My politics on the deficit are centrist to dovish. I think that deficit spending is always an option, and that the Federal Government should absolutely spend on forward-looking, high-return investment projects. I also favor generous “safety net” benefits and would like to see a guaranteed income program in the United States. However, the only form of “stimulus” I support is very broad based transfers (e.g. I would support a payroll tax subsidy). I agree with many left-ish commentators that the deficits we’ve experienced are more an effect than a cause of our economic problems, and will take care of themselves if we create a strong economy and a broadly legitimate political system (neither of which I think we have right now). A nation as large and wealthy in natural resources and human capital as the United States need never be constrained by the vicissitudes of financial markets, if its government is capable of mobilizing its citizens’ risk-bearing capacity on behalf of the polity. [*]

But whatever my politics, I think there is a fair probability that the US will experience the thrilling uncertainty that attends a loss of confidence in its currency and debt. The argument that “markets don’t seem troubled by our deficits” is less persuasive than it first appears.

Full disclosure: Although my views are sincerely held, sincerity is cheap. Perhaps I am just talking my book! I am one of those people long gold and short Treasuries (although I am not a proponent of the gold standard).

[*] Remember, economic capital has nothing to do with money. Supplying capital is nothing more or less than assuming the burden of economic risks. Where do you think China’s ever-expanding capital base comes from, when it has been the world’s largest exporter of financial capital? China’s citizens assume great risk, in the form of below-world-market wages and social safety benefits, in exchange for the promise of a wealthier and more powerful nation. To some degree that capital is extracted involuntarily, but China’s government has had remarkable success at maintaining legitimacy and the consent of the governed despite the extraordinary costs citizens have borne in the service of an uncertain future. So far, citizens have seen consistent returns on their investment: the big question is how China fares in a persistent “bear market”, when it comes to seem as though much of their sacrifice has been wasted or stolen.

Hi Steve,

For some reason, the pictures aren’t showing. When I copy the URL (e.g., http://www.interfluidity.com/v2/files/yield-10yr-crisis-period-2010-03-28.png) and paste it in a separate window, I get a “page not found” error message.

Michael

March 28th, 2010 at 7:43 am PDT

link

SRW,

1. The yield curve doesn’t reflect risk alone. It reflects expectation, which is not risk per se. We should differentiate between the expectation for future short rates and the risk around that expectation.

2. The current yield curve reminds me of Greenspan’s “conundrum”. He was puzzled that long rates didn’t increase when he tightened fed funds last decade. It’s part of his explanation as to why he blames the “abnormal” non-tightening response of long rates for the housing bubble, rather than his low short rate period per se. I never believed that a conundrum existed, and I see it more or less repeating that way (as an observation, not a central bank complaint) in the next up cycle – i.e. the expectation for required tightening is reflected mostly in today’s steep curve. The initial steeper curve in both cases reflects the structural uniqueness of an immovable zero lower bound. It’s a coiled spring yield curve as opposed to one that floats up or down by movements at both end. (A classic counter example is the 1993-1994 tightening cycle, which moved long rates substantially on a proportionate scale, starting from short rates at around 3 per cent). I don’t see the curve as a big risk premium. I see it largely as the expectation/hope of more normal yield levels and a curve that trends to flatter when the Fed tightens.

3. Short treasuries may work as a trade, more in 2’s than 10’s, but get out when resulting curve triggered re-deflation risk extends the expectation for low Fed policy rates.

March 28th, 2010 at 9:07 am PDT

link

Pictures show with explorer but not with chrome.

March 28th, 2010 at 9:17 am PDT

link

Michael, JKH — Thanks for letting me know about the broken images. I was using relative links which resolved (as Michael found) to a bad URL, but unfortunately Safari and apparently IE are too clever by half and covered up for my mistake, so I didn’t notice…

JKH — Yeah… I know that usually people subdivide what I’m calling the term premium into the expected interest path and the term premium due to liquidity/unexpected inflation(/default?) risk. I’ve agglomerated all of that into an “all risk” term premium. From the perspective of a long-bond buyer, an interest rate rise is a risk for which she demands compensation, even if it is priced into forward yield curves. (The change is not certain, even if it is in some sense “the market’s” expected value.) From the perspective of evaluating market evaluations of the “trustworthiness” of a government with respect to its currency management, the expected interest rate component has to be in the measure, because market participants may expect interest rates to rise due to an uptick in real activity (triggering an ordinary monetary policy response), or due to inflationary pressures (triggering either a monetary policy response or an inflationary accommodation, in either case requiring compensation). If markets are anticipating inflationary pressure (whatever the response), that’s substantively a point against the “bond yields prove that markets are unconcerned” view.

One benign explanation for this “conundrum” is that there is a “normal” long-term rate, and extraordinary low short-term rates have just pulled down the spread relative to a fixed ceiling. (From some theoretical perspectives, very long-term interest rates should literally be unchanging.) That may be right, but it is not obviously vindicated by the data: in practice, US long-term rates have been quite variable, and one would characterize them more as trending than mean-reverting. I think this is similar to your “coiled spring” view.

I won’t argue that these more benign interpretations are wrong. It may well be that markets are anticipating a solid recovery and a normalization of monetary policy, which might well lead to a Greenspan-conundrum-like flattening of the yield curve, with short rates rising and long rates falling as whatever part of the long end is risk-related falls away. The consistently moderate spread between TIPS and unprotected Treasuries argues for a not-inflationary interpretation (although even in theory that can’t differentiate between not-inflationary because the Fed fights back at the expense of output from not-inflationary because the economy recovers). Overall, I don’t think that bond markets (or markets generally) arbitrage well over long periods of time, though, so I’m skeptical of reading very much into the TIPS/Treasury spread. It’s a data point worth considering, but I think clientele effects as well as the widely accepted liquidity effects affect the price of TIPS more than they hypothetical long-term arb.

The elevated term premium / steepness of the yield curve is certainly not a “slam dunk” case for market skepticism of the Treasury as a borrower. But neither are the low absolute yields a strong case for market confidence. Overall, I think don’t think yields tell us very much either way, they just become a market Rorschach test in which commentators see whatever they want/expect to see.

p.s. in the little China postscript, there are shades of your influence, specifically your long-ago conjecture that taxation is analogous to equity in government. i think it is very interesting to consider ways in which people provide capital, bearing economic risk in exchange for uncertain future benefits but without formal assets to mark their claims. consensual taxation (meaning despite grumbling, taxation widely perceived as legitimate with which individuals generally comply) is very much like equity — you part with your money in hopes that it will be used well, and generate public goods worth the personal cost. of course, nonconsensual expropriation (of money taxes or labor) can also generate capital, it is just less analogous to market equity. i think China’s capital conundrum — a recently capital-poor nation that has continually expanded both its internal capital base while exporting financial capital — is fascinating, and helps think about the deeper sources of economic capital.

March 28th, 2010 at 11:16 am PDT

link

When short-term rates are artificially low, it seems that the term premium is less useful as an indicator. As the fed moderates short-term rates, long rates won’t necessarily rise an equivalent amount, and this would reduce the term premium.

March 28th, 2010 at 11:58 am PDT

link

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Edward Harrison, Abnormal Returns Now. Abnormal Returns Now said: interfluidity » A different perspective on interest rates http://stk.ly/9bTWXv $$ […]

March 28th, 2010 at 2:02 pm PDT

link

[…] What happens if markets get spooked by US government deficits? (Interfluidity) […]

March 28th, 2010 at 2:14 pm PDT

link

A little off topic, but not too much since it still involves those bond interest rates. Perhaps you’ve seen the whole Kinsley-Krugman (hyper) inflation pas de deux. Much ado over nothing, I surmised, since they did much to talk past each other. Krugman tries to distinguish between “moderate” inflation (say, 4 to 20%) and “hyper” inflation (some magical cutoff number that includes Zimbabwe and the Weimar Republic?).

Kinsley, on the other hand, was merely trying to express his non-technical but politically-intuitive instinct that when American politicians would be faced with severe budget challenges, and they had to choose between raising taxes and cutting spending on the one hand, or “high” inflation on the other, they would choose the other and go knocking on the central bank’s door. This is, I think it is fair to say, the exact sentiment Krugman himself expressed in 2003.

At any rate, Krugman has, on occasion, used our historically low interest rates to argue that the wisdom of the market does not expect even “high” inflation to arrive any time soon.

Now, it’s true that rates are low, and it’s a fact which deserves due consideration. But how often were the markets right about high-inflation levels in countries all around the world five or ten years prior to the enactment of government (or central bank) policies explicitly encouraging (or perhaps passively allowing) high inflation levels? Not very often, I would guess. Almost tautologically, debt-relief debasement policies would always have been null if the inflation they caused had been expected by the market at the time when the money was borrowed. If Greece defaults or leaves the Euro, it certainly wasn’t well-predicted five years ago.

Considering just the US post-war situation though, did the market accurately predict the two-year spike of double-digit rates (topping out nearly at nearly 20%) from July 1946 to July 1948, (and another spike during all of 1951)? No, in either case.

Perhaps some people, cynically savvy of the temptations to debasement of a debt-overburdened government of a war-and-sacrifice-weary nation, saw these things coming, but not “the market” in general, and probably not all those buyers of low-interest long-term war-bonds who watched a hefty portion of the real value of their savings disappear in those 24 months.

Indeed, one of the arguments for not worrying about the present level of debt is that, “It was over 100% of GDP in WWII, and we managed that.” Well, they had the advantage of certain societal conditions which we do not – the population growth rate was high, the US dominated global industrial production in the aftermath of a world war which devastated all our competition, longevity and entitlement spending was low, there was this thing called the baby boom, the debt was mostly domestically owned, and, oh yes, there were intermittent periods of high inflation, unexpected by the market at the time creditors loaned their money to the government at low interest rates which helped to erase the real value of the debt.

War bonds (the last sold in early 1946, I think), were 2.9% percent (annual) ten year bonds. A old neighbor of mine when I was growing up still had on of the original cardboard cutouts, where you could pop in your 75 quarters ($18.75) in return for a bond promising you $25 in ten years. He was the only one in most of my life to inform me about the post-war inflations. Everyone else always talked about the late 70’s, but he remembered the late 40’s and said they were really bad as well. He thought he lost a lot of money on his bonds, but nobody else but him seemed to remember those details that far back.

Now, the government eventually allowed the terms to be extended for several decades, but let’s say you bought one during the war and you took your $25 in the 1950’s. Using this neato online calculator we can find the decadal inflation rate: Jan 1942-52: 68.8%, 43-53: 57.4%, 44-54: 54.6%, 45-55: 50%.

But the bonds only got 33% after a decade, so no matter when you bought your liberty bonds (and I think over half the country – or 80 million people – did, and at over $2,000 worth per saver and in 1940’s money in the midst of a world war!) you experienced a significant real loss (and the government got a significant escape from war indebtedness) when you collected your proceeds.

It could be worse, the decadal inflation from Jan 1973-83 was 130%! And did the markets of, say, 1970, demand interest rates consistent with a prediction that the US dollar would lose a full half of it’s real value in only eight years between September 1973 and September 1981? No, it did not. Not even close. Yes, of course, there were the oil shocks, but depreciative policies as well.

So, in the end, I think I give the point to the Kinsley/Old-Krugman combo. When times get tough, inflation is awfully tempting, and the bond markets several years ahead of a “policy-event” don’t seem historically very good at demonstrating accurate expectations about the future until, suddenly, they shift all a of sudden in a shock. I hope that’s not our future.

March 28th, 2010 at 4:14 pm PDT

link

SRW,

Morgan Stanley forecasting 10 year treasuries at 5.50 per cent by year end.

They can’t be looking for much Fed tightening, so that’s an interesting yield curve they see.

If there are any value at risk models left on Wall Street and being used for yield curve analysis, they’ll have smoke coming out of them on that one.

Can’t see it.

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=az3WzaAg520U&pos=3

March 28th, 2010 at 10:17 pm PDT

link

“deficit spending is always an option… A nation as large and wealthy in natural resources and human capital as the United States need never be constrained by the vicissitudes of financial markets”

the combination of being a ‘hyperpower‘ and having a fiat reserve currency (not uncoincidental!) is a heady mix :P walter russell mead talks in god & gold about how:

we’re living in the republic of the central banker: “All this evolved not by design but by accident. The Bank of England did not start out thinking its job was to rescue the banking sector in crisis; it just found there was a crisis and thought it could do some good. Robert Peel did not set out to create a central bank, but prosecuting the Bank of England for charter violations seemed a mistake at the time. The Bank of England did not set out to supplant the market and turn the interest rate into a centrally planned and administered price, but monetary management in extraordinary times led to monetary management in unusual and then in ordinary times.” every hundred years or so: “it was the bankers themselves, led by Paul Warburg, of the merchant banking firm of Kuhn, Loeb, who laid out the basic design of the Fed…”

March 29th, 2010 at 8:49 am PDT

link

also btw, fwiw… paul mcculley (he of the shadow fed ;) is back with the modern day equivalent of the gold standard, “a nominal rate of interest on money that makes the holder whole for the two taxes that our government imposes on money: the explicit tax on nominal interest and the implicit tax of inflation.”

thus he argues

famous last words!

March 29th, 2010 at 9:02 am PDT

link

Doesn’t the spread just show that long-term expectations are getting close to normal again while short-term rates are unusually low? Economic downturns cause rates to drop, but the effect is bigger on short-term rates than on long-term rates, so the spread increases. That doesn’t mean that the market is growing more concerned about the long-term risk of holding Treasury bonds, just that they expect that their eagerness to hold Treasuries will be temporary.

March 29th, 2010 at 11:00 am PDT

link

Interesting comment on your post from Felix:

“I think it’s fair to say that the historical connection between the Fed funds rate and Treasury bond yields is largely lost when the overnight rate is at or near zero. Indeed, that was one of Alan Greenspan’s big mistakes: he dropped rates so far that he lost control of long-term interest rates. If the Fed funds rate is at 5%, you can turn the steering wheel and see an effect at the long end of the curve. If it’s at 1%, that mechanism becomes much squishier.”

hmm…

http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2010/03/29/when-bloggers-examine-the-treasury-market/

March 29th, 2010 at 1:49 pm PDT

link

[…] A different perspective on interest rates Steve Waldman […]

March 29th, 2010 at 2:15 pm PDT

link

[…] Parsing interest rates and the yield curve: what does it portend for the economy? […]

March 29th, 2010 at 6:27 pm PDT

link

Steve, I think everything that the modern monetary theorists say about the central banks, not the markets, setting longer term rates is true, but there is also the impact of short term private portfolio liquidity preferences (we seem to be looking at the latter dynamic right now in the US with the sell-off in bond yields, despite little news to affect rates). I think there is a way to deal with this. First of all, the Treasury can simply calibrate the offerings on its various maturities to better match market demand. If there’s poor demand for, say, 10 year, then offer more 2 year money.

There’s also another potential course of action by the Fed to influence or mitigate the impact of these short term private portfolio preference shifts. Do you remember Operation Twist?

Now the Fed has the tools to make it actually work, unlike the last time.

Tell everybody you are renormalizing the fed funds rate and take the Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER) up to 100bps. You don’t need to remove any reserves to do this – you just do it administratively. That’s how the IOER works – it severes the link between reserves in the system and the target policy rate, right?

Then, if the bond gods don’t rally Treasuries on your noble effort to renormalize the policy rate, you call up Dudley at the NY Fed and give him instruction to buy all the 10 year UST on offer until the 10 year UST yield is down to, oh , say 3.5%. It is an Open Market Operation (OMO) – you do this all the time. You won’t have to call it QE, but it is in effect the same thing.

Then, every time some big swinging dick bond trader tries to push it above 3.5% by shorting Treasuries, you slam their face into the concrete by having the

the open market desk buy the hell out of UST until the 10 year yield is back to 3.5%. Burn Fido enough times, yank his chain enough times, and like the Dog Whisperer, he gets it and stops.

Operation Twist, Part Deux. Only way to finesse the expectations management dilemma.

March 29th, 2010 at 8:34 pm PDT

link

Herr Marshal

“Then, every time some big swinging dick bond trader tries to push it above 3.5% by shorting Treasuries, you slam their face into the concrete by having the

the open market desk buy the hell out of UST until the 10 year yield is back to 3.5%. Burn Fido enough times, yank his chain enough times, and like the Dog Whisperer, he gets it and stops.”

And I certainly hope we see gold at 10,000 the next day.

March 29th, 2010 at 10:32 pm PDT

link

Question: does it make sense to think of long Treasury yields as accurate reflections of market expectations when one of the largest players in the market only buys and never sells regardless of fundamentals?

March 30th, 2010 at 7:01 am PDT

link

Well, I’m in way over my head here, but the inflation calculator cited above is, I think, significantly off. The only advantage(disadvantage?) that I have over most of you is that I’m older.

My point is, as someone who has lived it, that the inflation calculator estimates inflation from the mid-Fifties to now as roughly sevenfold. I would say without hesitation that tenfold would be more like it.

March 30th, 2010 at 9:00 am PDT

link

Wow, some great comments. I’m sorry, as I often am, to be a comment response deadbeat (as I often am).

JKH — If MS is right about 5.5% ten-year yields by year end, unless the Fed takes something very far from a measured pace, then wow. That’s blow out the yield curve. That said, their forecast looks to be an outlier. (But as a Treasury short, I can always hope!)

John P & Dan & Felix as channeled by JKH — Good points, absolutely. Fear of inflation, default, deficits, etc are only one of many possible explanations for the steep yield curve / term premium. My little chart is not serious evidence that deficits are spooking the market, only a rebuttal to the notion that falling absolute yields are serious evidence that they are not. Undoubtedly, part of the steepness of the yield curve reflects expectations that short-rates will rise. It’s worth noting that rising short rates have a benign and a less benign interpretation. They could mean a good economy, or they cpuld mean inflationary pressures the Fed decides to push against in a bad economy. That is, expected high short rates is not inconsistent with a deficit-related expectation of increasing inflationary pressures.

I wrote a follow-up to this post last night on just these themes, but decided the insight to verbiage density was too low to merit publishing as a headline post. Maybe I’ll add a comment to see what you think.

Indy & glory — You guys are thinking very much like I do. Ultimately, whether the US experiences inflation or painfully sharp rate rises or increased taxation will reflect how the polity reacts to moment-by-moment problems. The US government has a wide variety of tools at its disposal, although the cynical might refer to some of them as “fudges”. Depending on the problems it faces, it can ease or contract monetary policy, it can spend, transfer, or tax, it can combine easy monetary policy with fiscal spending to effectively “print money”. It’s constraints are interest group politics — inflation is helpful to some and harmful to others and it comes in different flavors, same with unemployment (which is very helpful to those with savings and no need to work as it puts a lid on the price of the economy’s most important commodity!), etc. There is arguably an overarching “public interest” in a good long-term economy — wise long-term aggregate investment, wealth distribution that balances incentives to excel with moral and social stability concerns, etc. Real governments face real constraints, and use tools to solve problems. Whether those solutions are wise beyond the shortest-term is the question. There will undoubtedly be temptations to “print money”. I’m actually more concerned about the temptation to appease the “investor class”, which means guaranteeing their bad investments while assiduously fighting inflation. I’d be in favor of a certain sort of inflationary policy, but path-of-least-resistance guarantee-and-spend policies won’t do it, will inflate away the value of wages along with helping debtors and appeasing rent-seekers. Unfortunately, echoing some of your cynicism, the worst-of-both-worlds sort of inflation that rewards poor past investment while increasing the price of commodities relative to labor, strikes me as a very likely scenario. It’ll get called a “supply shock”.

March 30th, 2010 at 3:38 pm PDT

link

James K — Bond yields are only a “true reflection” of bond prices. Every market is populated by all kinds of actors who may have interests in affecting price dynamics as well as in the good, service, or promise being bought or sold. Whenever we tell stories about prices, we have to keep that in mind. Prices in general, but especially capital market prices, are much noisier than we imagine, and most of our narrative uses of them amount to mythologizing.

Bernie M & Indy — The cynicism begat by your experience is the sad driver of the gold market. As the MMT-ers often remind us, fiat money is remarkably flexible and a wise government could do a lot of good if it could be relied upon to use that flexibility well. If governments were wise, gold would be a barbaric relic, and it ought to be. Holding gold, for me, is an act similar to voting for third-party candidates in elections. It is a way of signaling lack of confidence in the dominant institutions of finance and government (albeit the sort of “vote” that can pay or ruin you, depending both on the “accuracy” of ones characterizations, as well as a lot of active struggle and random noise).

March 30th, 2010 at 3:47 pm PDT

link

Marshall & Cedric — There’s no question that the MMT view gets the operational details and the broad capacity of the central bank right, putting aside political questions and constraints.

There’s be no need to be very clever, right? The techniques you propose would be a way of trying to combine managed long-term rates with a pseudo-hands-off Treasury market (and might well work, although Cedric’s comment might become relevant). But a central bank can simply declare a ceiling on yields anywhere out the yield curve, and demonstrate a willingness to purchase bonds in indefinite quantities at that yield if private market participants do not. It’s interesting to consider whether and why the sort of random-reinforcement “whack-a-mole” that you describe would be more useful than an outright administered price.

I do, by the way, think there are circumstances where “whack-a-mole” might be the right game for a government to play. That wasn’t intended as a veiled dismissal of the idea. But as far as Treasury bonds, I wonder why a government would bother. If a government were persuaded, per the MMT view, that tax policy is a better way to maintain than messing with interest rates, why not go to Warren Mosler’s zero risk-free interest rate all the way out the yield curve?

I guess that takes us back to the real world, full of its fudges. If we don’t have the balls (really the degree of political consensus) necessary to manage inflation by taxation (and make the distributional choices taxation entails), we rely upon high-priced money to discourage expenditure and pretend “markets” are making the distributional choices. But we might not like some “market outcomes” while we are still unwilling to make overt fiscal choices, so we “tweak” the market outcomes. That sounds like a way of understanding what you’ve proposed. It also sounds very much like what we actually do, although in a manner a bit less explicit, a bit more veiled and hedged.

March 30th, 2010 at 4:00 pm PDT

link

Another great post.

Shouldn’t the likelihood of a political outcome affect its viability as a policy option. For instance, you believe that a properly managed fiat currency can yield benefits to the nation. However, you don’t see our fiat currency as properly managed, nor does it seem that fiat currencies have been properly managed for long periods of time throughout most of history. You also base your own investing on such cynicism, when push comes to shove. I’m of the same opinion on the matters of bother theory and practice.

I think there are fundamental political and logistical impediments to micromanaging a fiat currency well. The best government policies which help the most people are those that are simple, easily understood by the populace, transparent, and less prone to special interest capture. A road, a firetruck, a water sanitation plant. People can understand the need for them, running them does not take super intelligent politicians or regulators, and its difficult to twist and corrupt such basic services. A well managed fiat currency, on the other hand, seems an almost impossible task. It lacks simplicity, it isn’t well understood, transparency can easily politicize decision making, and it is prone to special interest capture, even if its of a purely intellectual nature.

So if a well managed fiat currency is an extremely unlikely political outcome, does the theory really do us any good? Don’t get me wrong, I think good political theories serve as a nice basis for thinking about policy. And I don’t think policy has to be perfect. But it should at least be decent, and I don’t know if our track record on micromanaging interest rates has proven to be any more effective then when we had more simplistic monetary policy and tried to do less.

You can substitute deficit spending for monetary policy in that passage and it has the same effect.

March 30th, 2010 at 8:55 pm PDT

link

A follow up.

When I say politically possible, I don’t really mean the politics of the moment (we can’t do X because we don’t have the votes). Political preferences shift over time and are rather fickle, as is the current party or persons in power. Rather I mean permanent or semi permanent institutional issues which make certain policy choices less viable. As an example, barring an extremely unlikely constitutional amendment the less populous states will always have disproportionate political power in the senate since everyone is guaranteed two seats.

As far as conducting good monetary policy there are so many political issues with it that it just hasn’t worked over long periods of time in nearly any culture. Deficit spending too tends to end the same way. Deficit spending can enable good economic investments by government, but it can also be a way to shield the true cost of disastrous economic policies form the public until its too late. In countries that have a long track record of big deficit spending the latter tends to be the case more then the former.

March 30th, 2010 at 9:20 pm PDT

link

I’m not a gold bug, just someone who saved retirement savings the way the old, simple world said it was supposed to work. All I see this past decade is dangerous manipulation by government and TBTF banks that shift low yield and high risk to anyone not with a TBTF backstop. I’d like to play along he concept of fiat currency, but a real, low risk, after tax return is the only thing that makes it work. I don’t like it when the government sets up the rules that the only ones that make money(many millions) are TBFT traders working with my ZIRP funds, backed up with my tax money if something goes wrong.

Then if they short at 30X leverage the government cries foul.

March 31st, 2010 at 2:09 am PDT

link

dave — the reason to prefer fiat currencies isn’t because governments are capable or likely of managing them well, in the sense of preventing unjust transfers and inflations. they aren’t and won’t be, at least not indefinitely.

the reason to prefer fiat currencies is precisely because the managers of anything that becomes a currency will debauch it eventually, and fiat currencies fail more gracefully than redeemable currencies. it is analogous to the difference between debt and equity. an enterprise can succeed or not succeed regardless of how it’s financed. but when an equity-financed enterprise runs into trouble, its equity is devalued but the enterprise continues. when a debt-financed enterprise runs into trouble, the claimants all feel entitled to value that is no longer present, and often destroy the enterprise trying to extract it.

further, holders of debt — like holders of gold-backed currency or holders of euro — often fail to monitor the solvency of the enterprise that backs their claims until it is very much too late. with fiat currency, everyone knows what they hold could be worthless. if the US were to “back” dollars with gold @ 10K an ounce, we’d have a nice, hard currency for a while. but eventually, we’d slip into “fractional reserve” issuance of currency — still redeemable, so hey, everyone feels safe! the fraction would be modest, for a while, but it would slip. finally, there would be a run on the currency, and it would break, and rather than a subtle devaluation we’d have a hard default all over again. it’s extraordinary that FDR managed his default on the gold standard with as little social turmoil as he did.

finally, sometimes inflation is a feature not a bug. first, routinely, an inelastic currency in a growing economy tends to appreciate in real terms, creating unearned rents to holders of currency and discouraging active participation in the reproduction of wealth. wealth is not storable, it must be actively recreated every day. it is more than sufficient to give holders of money the gift of pushing wealth forward in time without work or cost. holders of money ought not be permitted to extract wealth from those who actually produce it merely by virtue of acquiring money early. secondly, sometimes the transfers of wealth that are made possible by “debauching” a currency are in the public interest. now would be one of those times. in a financial system too riddled with debt, devaluing debt by default may engender destruction of real economic capacity for no good reason. perfectly viable enterprises may be liquidated because holders of debt prefer certain recoveries to a continuing a franchise that would over time have positive value, given its average cost of capital, but is leveraged and can’t meet cash flow demand. further, people react badly to defaults and the prospect of default, and may kill viable enterprises by calling or failing to rollover debt when financing is scarce. during “credit crunches” it’s nearly impossible to distinguish between viable but illiquid and genuinely insolvent enterprises. When enterprises are mostly equity financed, they cannot be illiquid with respect to creditors, and to the degree they face hard times, stockholders do everything they can to maximize enterprise value, since they generally recover very little in a liquidation. the “crunch” is reflected not in bankruptcy but in low stock prices that may or may not recover. during hard times, inflation can be used to “equitize” debt. in nominal terms, debt can’t devalue like stock. but it can in real terms, given inflation. enterprises that are ultimately not viable in real terms won’t be saved by devaluation of debt. for viable firms, devaluation of debt ends up amounting to a transfer to equityholders, who find their enterprise less indebted in real terms after the storm. that may be unfair (but the prospect of inflation encourages smart debtholders in a viable enterprise to voluntarily trade debt for equity in difficult times to capture some upside on recovery).

just as the best thing for potentially viable firms with an unmanageable capital structure is bankruptcy, aggregate reorganizations of claims are sometimes helpful. under a gold standard that is difficult to do. under fiat, you just inflate. “just” is a bit glib, because inflationary depressions are no fun, terribly messy, sometimes catastrophic. but reorganization and recovery is more possible via inflation than via default and taxation/redistribution under a gold standard.

of course, governments can inflate badly. just as the existence of bankruptcy doesn’t guarantee a value-conserving outcome in a bankruptcy court, the flexibility offered by a fiat currency may well be used badly. but the only way gold standard societies reorganize, historically, is by giving up or weakening their gold standard. which they always do, because governments and nations always fuck up eventually, where eventually is less than a century long.

to sum up, i like fiat currencies not because they don’t fail, but because they are capable of failing more gracefully.

[of course, i dislike that fiat currencies can be abused to enable unjust transfers (e.g. printing money for real-economy-destroying bankers), but then i see little evidence that gold standard societies avoided corrupt accumulation by elites. corrupt accumulation in a fiat regime can be undone by inflation. money must be taken back by force under a gold standard regime.]

ideally, my preference is for multiple competing currencies, all of which would be “fiat” in the sense of conferring no legally enforceable redemption rights upon its holder, but which would compete to sustain value by voluntarily offering unenforceable redemptions. think gift certificates from firms that have every right to change the price of their goods. i can hold my wealth in Amazon points, but if Amazon distributes too many points, it can increase the price of all its merchandise, thereby reducing the real redemption value of my currency. so i’d want to monitor Amazon if i saved in their scrip. (government currencies would fit immediately into this world: governments manage the redemption value of their currency by balancing economic management with taxation. governments that steward economies that are both productive and highly taxed generate citizens willing to redeem currency for goods and services, and people would want to hold the currencies issued by such governments.)

blah!

March 31st, 2010 at 2:21 am PDT

link

On the fiat currency issue, the allure of the “Soft Fail” seems so inadequate for some of us, and this has, belatedly, made me wonder if I should become a gold bug.

One of the reasons to become a goldbug, say goldbugs, is lack of counterparty risk. But now we have the convenience of gold ETFs, which solve the problem of physical delivery and storage for us, provided we continue to believe that is a problem, and not a necessity.

I have been hearing there could be counterparty risk problems in gold/silver ETFs or at least maybe the underlying commodity markets really can’t deliver on physical gold, if demanded, and leave us holding worthless paper/electrons after all.

I was wondering if Steve has an opinion on this, and if he has figured out a better way to be a safe goldbug?

March 31st, 2010 at 12:04 pm PDT

link

Cedric — Holding gold doesn’t make one a “goldbug”. There is a world of assets out there, and one makes different choices at different times. Gold is one among them.

I absolutely positively don’t give investment advice. I only reveal my own positions when they may conceivably color the views expressed in a post, and readers ought to know that.

My own gold positions are a mix of futures and ETFs. Physical gold may lack counterparty risk, but holding it involves storage costs, physical security, and fraud risk. I wouldn’t be capable of telling a bar of gold from a bar of gold-plated tungsten. If I owned physical gold, it’d be placed in a bank deposit box, but that adds confiscation risk — if the government were to remonetize gold (an outcome I don’t particularly advocate, but consider possible if there is a loss of confidence in its fiat), it might well demand it be surrendered at a set price, and banks would ensure compliance with respect to gold in safe deposit boxes. There are various domestic and off-shore “gold banks”, but I don’t know why I should trust them any more than clearinghouses and regular banks. I think most “gold bugs” would say I’m overly fatalistic about this stuff, and in part I am just lazy and comforted by the apparent liquidity of “paper gold”. I hope we avoid the very apocalyptic scenarios in which physical gold would actually be necessary for exchange, and I want to be able to exit quickly if gold becomes so popular governments will have no choice but to confiscate it or “whack it down” by taxation or any number of other means.

Again, I absolutely don’t recommend you follow anything that I do. I am a very middling speculator at best, and sometimes much worse than that. I’m uncomfortable with ETFs, uncomfortable with futures, uncomfortable with physical, and I do what I do.

March 31st, 2010 at 5:51 pm PDT

link

Agreed that goldbugedness is either permanent or temporary insanity, depending on the individual and the state of the financial world. All the pros and cons of owning physical vs paper gold have crossed my mind as well, and there were periods in history when it wasn’t even safe to keep it in your teeth.

The fact that if you “win” holding gold amongst a global race to the bottom in fiat currencies, you are then taxed for your good fortune is quite annoying. So far I’ve been playing dollar weakness, when we have had it, via global bond funds and there I’ve had the same annoying problem of being taxed for my “capital gains”.

My first choice is still being paid interest somewhere in the world, but I guess I may go the gold ETF route on a pullback (unless the pullback was due to sudden emergence of central bank support of currency) and try not to worry that it is only paper gold.

March 31st, 2010 at 6:24 pm PDT

link

Steve,

Excellent thinking. You make an important and thought provoking point with your last two graphs. Here are some thoughts on this:

1) The term premiums are high by historical standards, but how much of this is this because bond buyers fear inflation and how much is because they fear a default on US Government bonds? You could have estimated the size of the two effects by i) seeing what the CDS on U.S. government bonds currently is, and ii) by seeing what the implied future prediction of inflation is from comparing TIPS with US Government bonds of (about) the same term. This would have been a nice addition to the post – but time time, so scarce.

2) I wouldn’t put too much stock in the markets accuracy. We’ve seen market participants can be highly inefficient, and savvy margin buyers are restricted by liquidity and increasing undiversification as they buy more of the same underpriced asset. Try graphing the TIPS implied inflation forecasts over 10 year periods (the assumed inflation rates over 10 years from comparing 10 year TIPS to 10 year fixed US bonds) from just before the crisis until now. That would be a very interesting informative graph (if you have the time) and I think it would show market forecasting to be far from efficient.

3) The Republican Party has gotten so extreme, so anti-thinking, anti-science, anti-intelligence, that I actually agree that the probability of something as utterly stupid as a default on US debt has more than a nano chance of occurring. Remember that only about 20% of the population is Republican. Half that 20% is pretty much the craziest 10% in the US. A quarter is the craziest 5%. Now that’s a group that’s very out of touch with reality. Next, consider a closed primary. And consider that most people don’t vote in primaries, and especially caucuses, but the craziest 5%, 10% of the population are very passionate and motivated. They go to polls and caucuses in high proportions. That craziest 5-10% of citizens can get their nuts and/or morons nominated. Then big money special interests and the propaganda machine shifts into high gear, and it can happen. So, although a default on US debt is nonetheless extremely unlikely, it’s not a nano chance.

4) We need to raise taxes on the wealthy over the long run to turn long run deficits into long run surpluses, just as Clinton did before the Republicans brought us back to their normal giant tax cuts for the rich and giant deficits. For now, with the recession, deficit spending is best, but there should be long run tax hikes on the wealthy, and on carbon, and other negative externalities.

5) The filibuster must be abolished to accomplish 4. For more on this, please see:

http://richardhserlin.blogspot.com/2009/08/key-reason-why-51-democratic-senators.html

March 31st, 2010 at 6:34 pm PDT

link

SRW,

Note from Krugman on the curve:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/03/31/a-note-on-the-term-spread/

“Anyway, back to the term spread: all that huge spread is telling us is that we’re up against the zero lower bound, but that markets think we may not stay there.”

hmm … again … linking the curve specifically to the zero bound

March 31st, 2010 at 6:36 pm PDT

link

Here’s another point:

Inflation right now is zero or negative, and there still a lot of fear, so super safe short term US bonds pay close to zero interest; that’s something the Fed can easily enforce in this environment and wants to. This is an unusual situation historically.

Now, if a smart inflation rate to target is 2 to 4 percent, then seeing term premiums of 2 1/2 to 4 1/2 percent may be nothing to worry about at all, just a sign that the market thinks that the Fed and the rest of governemnt will do the smart thing and be successful over the next 10 to 20 years.

March 31st, 2010 at 7:16 pm PDT

link

I’dd add to point 3 in my first post, throw in that a lot of people who are smart and not crazy can still vote for a Sarah Palin just becasue they are very uninformed and/or superficial in their voting, and throw in a very bad economy on the Democrats watch and/or a terrorist attack, throw in lots of money from special interests, a powerful shameless ruthless propaganda machine, and a very Palin Republican Party can take power. It’s not out of the question.

March 31st, 2010 at 7:22 pm PDT

link

After reading bond experts for some time, I’ve decided that no one really knows why yields are what they are, except that supply met demand (or vice versa) for reasons too complex for mere mortals to understand.

One thing I have heard quite a few “experts” say is that TIPS are not a valid indicator of inflation expectations. Couple reasons, it is a small and illiquid market. That is because the typical TIP owner is a grandma or pension fund, and they are not considered to be the “sophisticated investor class” manning the bond trading desks.

The other thing that gets missed by many is that bonds come with credit ratings(silly as these may be) and therefore there is supposed to be a gradual pricing on payment risk, not 100% zero risk vs 100% default risk as is the model seemingly employed by Delong and Krugman when evaluating the US treasury market.

Then throw in factors like is the money supply going or coming, global flight to and from safety, QE on long term credit, the global carry trade, currency pegging to the dollar, CDS, and lots of bond traders that don’t concern themselves with simple concepts like “up, “down”, and “yield”, but are really concerned with making highly leveraged bets on the shape of the yield curve changing, or spreads on up the risk spectrum changing, it is a wonder that anyone would try gleaning economic insights from yields at all.

March 31st, 2010 at 7:28 pm PDT

link

Thinking about it, I think my second from last point is a key rejoinder Kruggie might make.

Your graph looks only back to 1977. How many recessions this severe occurred in that time? None. 1981-2 was very bad, but not like this. When was the Fed at the ZLB(Zero Lower Bound)in this period?

For this type of situation, with the Fed at the ZLB, a term premium of 2 1/2 to 4 1/2 seems perfectly fine, what you’d expect if you forsaw the future inflation rate being 2 to 3 1/2 percent. And there’s a very strong economic argument that the smartest inflation rate is somewhere in the 2 to 3 1/2 range. So your graph could be nothing to worry about, actually a positive sign.

March 31st, 2010 at 10:08 pm PDT

link

Yeah, I was right. Look at Kruggie’s current post:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/03/31/a-note-on-the-term-spread/

March 31st, 2010 at 10:25 pm PDT

link

Richard H. Serlin

I think Kruggie will be disappointed. I’m still trying to figure out how higher inflation is “smart”. I don’t know of any economists that refer to the ’70s in the US as “smart”. Brazil’s new economists and policy makers refer to Brazil’s 1970s thru 1980s economy as quite stupid. I had some biz associates there back then and they described it as pure hell.

I got a mortgage in 1981 for 12%. It took until 1990 until I could re-fi at 9%. I don’t recall the actual inflation data over that time span, but it declined much faster than mortgage rates, so from that you can assume that it is not smart to screw bond investors, because in the end they got it some of it back in real interest rates. And the real, pretax yield you are implying is one half percent to a percent on a 10 year term? When in history have we had that? Who would want it? (Do not answer the Japanese. They have a very large public pension plan buying most of their low yielding bonds. The unfettered money leaves the country for yield elsewhere.)

There are many ways for “smart” to backfire. For one thing, health care costs have proven to have a lot of pricing power and are not likely to be inflated away. Neither are energy costs. The Chinese may even decide manufactured products have pricing power. Inflation can even make debt deflation worse, because our ample supply of existing securitized debt will sell off, raising mortgage rates and pushing down housing prices further, and more people walk on their bad investment in housing. Inflation doesn’t guarantee higher wages, the point of it usually is to generally make us poorer. And the Treasury will be quite embarrassed if no one shows up for the auction parties.

I am aware that both Delong and Krugman routinely brush off these concerns as “stupid”, (in between posts where they publicly praise each others opinions) and also like to connect anyone with “stupid” views to Sarah Palin. But I’m not a Sarah Palin fan either, and I like my “stupid” views, and even take some comfort in the fact that Obama, Geithner and Bernanke think inflation is stupid, and want to stop doing stupid things as soon as the economy will allow.

March 31st, 2010 at 11:55 pm PDT

link

Cedric, no time for a long response, but first, I don’t mean late 70s level double digit inflation, I mean maybe 3-4%.

Some (potentially huge) benefits are:

1) The Fed has a lot more power to fight recessions, as they can cut real interest rates an extra 3-4% before hitting the zero lower bound when inflation is 3-4% than when it is zero.

2) Defaltion can be devasting to an economy, and if you shoot for 0 inflation you can easily mishoot and fall into deflation.

3) Real prices adjust better to efficient levels with 3-4% inflation than with zero inflation, as people are very resistant to wage cuts but much less resistant to a wage freeze during inflation which results in just as much of a real cut in earnings.

April 1st, 2010 at 2:16 am PDT

link

Another thing I’d add is during a stable period inflation is expected to stay where it is in the future. It’s not expected to go up and it’s not expected to go down (where I mean expected in the statistical sense, that is on average no change, but there’s variance around this forecast).

So in such a period, what would a term premium look like? It would still be positive and increasingly positive as the term got to be longer and longer.

This is because, you think on average there will be no change in inflation, but you risk being wrong and inflation gets higher and your interest is not enough to keep up, but your locked in for the term of the bond. So you demand a premium for inflation risk.

You are also locked in in your implied risk-free interest rate. If that gets bumped up, then your interest rate again falls behind the market interest rate, but you’re still locked in for the term. So you demand a premium for that.

And there’s a tiny premium for the increasing chance over time that the US government will default.

So because of these three premiums you would have a positive and increasing total term premium, that is the term structure of interest rates is that the longer the term gets the more interest you get on fixed rate bonds.

But now add in that we are not at all in a stable inflation period. We are in a very unusual period, one where the Federal Reserve and the fiscal part of government really want inflation to increase from its current zero or negative to about 2-3 1/2% (There’s a debate on what to target, but they’re talking at least 2). So if you think the government will be successful, then you will add another 2 – 3 1/2% to your normal term premium, giving us an unusually high term premium. But that would only mean that you think the government will be successful in increasing inflation a lot. And most economists think that’s a good thing starting in a severe recession with inflation at zero or negative.

April 1st, 2010 at 12:59 pm PDT

link

Ok, I see you’ve covered a lot of what I’ve said in comments. I know I should have read that first, but time, time. Anyway, the thinking out loud was helpful at least to me, and hopefully to some others. Thanks for the thought provoking post.

April 1st, 2010 at 2:16 pm PDT

link

I am long the long bond. I am not popular at parties.

You should be long the long bond, too:

(1) The forces that make the “term premium” so large, are likely caused by the zero % interest rates. Thus, when zero% interest rates end, the term premium will decrease.

(2) The fed has got our economy by the balls. Higher interest rates will kill the economy and inflation quickly.

(3) The market is coming around to modern portfolio theory. The reverse correlation of long bonds and stocks is growing. Mr. Market has realized that long bonds are miracle workers in the portfolio. You buy equities & you buy long bonds. If, at any time, equities tank, then your long bonds rally and you can cash them in when you need them the most (when stocks are on sale). In every other scenario you will get a coupon and 100% return of your money at the end of the term.

(4) There is no “secret story” that you or I are privvy to about the condition of our government that the crappy allocation of capital by our government, yet, the bond rates are what they are.

(5) This is my last point, connecting to previous point… a quote from a recent cheezball article: “What is truly striking is that even though Treasuries were among the best-performing asset classes of the past decade, the noncommercial accounts spent 80% of that time being short the bond market. Yikes!” It points out that a lot of people are short the long bond. http://www.minyanville.com/businessmarkets/articles/government-bonds-treasuries-trade-yields-positions/3/19/2010/id/27360?camp=syndication&from=yahoo

April 3rd, 2010 at 10:32 am PDT

link