Should markets clear?

David Glasner has a great line:

[A]s much as macroeconomics may require microfoundations, microeconomics requires macrofoundations, perhaps even more so.

Macroeconomics is where all the booming controversies lie. Some economists like to argue that the field has an undeservedly bad reputation because the part that “just works”, microeconomics, has such a low profile. That view is mistaken. Microeconomic analysis, whenever it escapes the elegance of theorem and proof and is applied to the actual world, always makes assumptions about the macroeconomy. One very common assumption microeconomists frequently forget that they are making is an assumption of rough distributional equality. Once that goes away, even such basic conclusions like “markets should clear” go away as well.

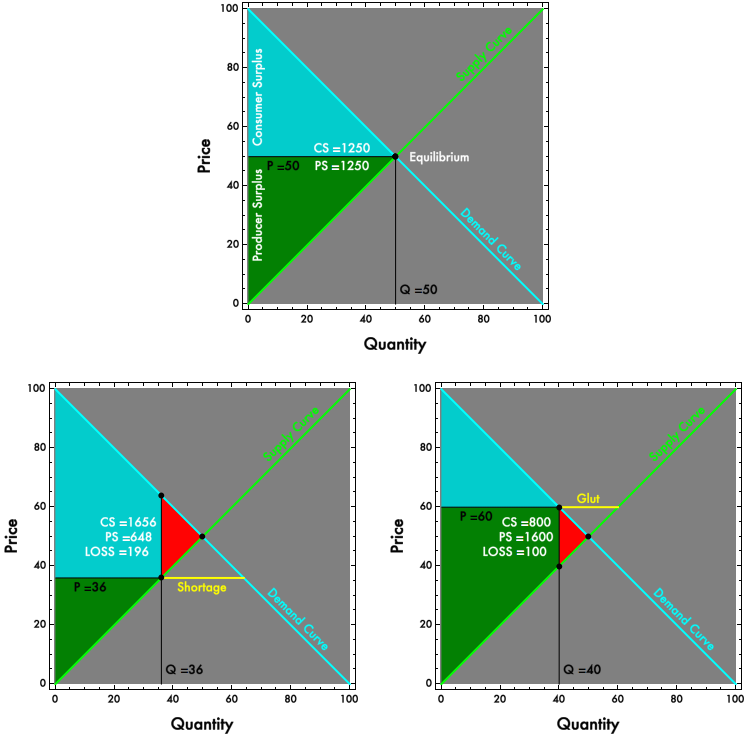

The diagrams above should be familiar to you if you’ve had an introductory economics course. The top graph shows supply and demand curves, with an equilibrium where they meet. At the equilibrium price where quantity supplied is equal to quantity demanded, markets are said to “clear”. The bottom two diagrams show “pathological” cases where prices are fixed off-equilibrium, leading to (misleadingly named) “shortage” or “glut”.

We’ll leave unchallenged (although it is a thing one can challenge) the coherence of the supply-demand curve framework, and the presumption that supply curves upwards and demand curves down. So we can note, as most economists would, that the equilibrium price is the one that maximizes the quantity exchanged. Since a trade requires a willing buyer and a willing seller, the quantity sold is the minimum of quantity supplied and quantity demanded, which will always be highest where the curves meet.

But the goal of market exchange is to maximize welfare, not to generate trade for the sheer churn of it. In order to make the case that the market-clearing price maximizes well-being as well as trade, your introductory economics professor introduced the concept of surplus, represented by the shaded regions in the diagram. The light blue “consumer surplus” represents in a very straightforward way the difference between the maximum consumers would have been willing to pay for the goods they received and what they actually paid for the goods. The green producer surplus represents how much money was received in excess of what suppliers would have been minimally willing to accept for the goods they have sold. Intuitively (and your economics instructor is unlikely to have challenged this intuition), “surplus over willingness to pay” seems a good measure of consumer welfare. After all, if I would have been willing to pay $100 for some goods, and it turns out I can buy then for only $80, I have in some sense been made $20 better off by the trade. If I can buy the same bundle for only $50, I’ve been made even more better off. For an individual consumer or producer, under usual economic assumptions, welfare does vary monotonically with the surpluses represented in the graph above. And market-clearing maximizes the total surplus enjoyed by the consumer and producer both. (The naughty red triangles in the diagram represent the loss of surplus that occurs if prices are fixed at other than the market-clearing value.) Markets are “efficient” with respect to total surplus.

Unfortunately, in realistic contexts, surplus is not a reliable measure of welfare. An allocation that maximizes surplus can be destructive of welfare. The lesson you probably learned in an introductory economics course is based on a wholly unjustifiable slip between the two concepts.

Maximizing surplus would be sufficient to maximize welfare in a world in which one individual traded with himself. (Don’t laugh: that is a coherent description of “cottage production”.) But that is not the world to which these concepts are usually applied. Very frequently, surplus is defined with respect to market supply and demand curves, aggregations of individuals’ desire rather than one person’s demand schedule or willingness to sell, with producers and consumers represented by distinct people.

Even in the case of a single consumer and a different, single producer, one can no longer claim that market-clearing necessarily maximizes welfare. If you retreat to the useless caution into which economists sometimes huddle when threatened, if you abjure all interpersonal comparisons of welfare, then one simply cannot say whether a price below, above, or at the market-clearing value is welfare maximizing. As you see in the diagrams above, a price ceiling (a below-market-clearing price) can indeed improve our one consumer’s welfare, and a price floor (an above-market price) can make our producer better off. (Remember, within a single individual, surplus and welfare do covary, so increasing one individual’s surplus increases her welfare.) There are winners and losers, so who can say what’s right if utilities are incommensurable?

Here at interfluidity, we are not in the business of useless economics, so we will adopt a very conventional utilitarianism, which assumes that people derive similar but steadily declining welfare from the wealth they get to allocate. Which brings us to our first result: If our single producer and our single consumer begin with equal endowments, and if the difference between consumer and producer surplus is not large, than the letting the market clear is likely to maximize welfare. But if our producer begins much wealthier than our consumer, enforcing a price ceiling may increase welfare. If it is our consumer who is wealthy, then the optimal result is a price floor. This result, a product of unassailably conventional economics, comports well with certain lay intuitions that economists sometimes ridicule. If workers are very poor, then perhaps a minimum wage (a price floor) improves welfare even of it does turn out to reduce the quantity of labor engaged. If landlords are typically wealthy, perhaps rent control (a price ceiling) is, in fact, optimal housing policy. Only in a world where the endowments of producers and those of consumers are equal is market-clearance incontrovertibly good policy. The greater the macro- inequality, the less persuasive the micro- case for letting the price mechanism do its work.

Of course we have cheated already, and jumped from the case of a single buyer and seller to a discussion of populations. Fudging aggregation is at the heart of economic instruction, and I do love to honor tradition. If producers and consumers represent distinct groupings, but each group is internally homogeneous, aggregation doesn’t present us with terrible problems. So we’ll stand with the previous discussion. But what if there is a great diversity of circumstance within groupings of consumers or producers?

Let’s consider another common case about which many economists differ with views that might be characterized as “populist”. Suppose there is a limited, inelastic supply of road-lanes flowing onto the island of Manhattan. If access to roads is ungated, unpleasant evidence of shortage emerges. Thousands of people lose time in snarling, smoking, traffic jams. A frequently proposed solution to this problem is “congestion pricing”. Access to the bridges and tunnels crossing onto the island might be tolled, and the cost of the toll could be made to rise to the point where the number of vehicles willing to pay the price of entry was no more than what the lanes can fluidly accommodate. The case for price-rationing of an inelastically supplied good is very strong under two assumptions: 1) that people have diverse needs and preferences related to the individual circumstances of their lives; and 2) willingness to pay is a good measure of the relative strength of those needs and values. Under these assumptions, the virtue of congestion pricing is clear. People who most need to make the trip into Manhattan quickly, those who most value a quick journey, will pay for it. Those who don’t really need the trip or don’t mind waiting will skip the journey, or delay it until the price of the journey is cheap. When willingness to pay is a good measure of contribution to welfare, price rationing ensures that those more willing to pay travel in preference to those less willing, maximizing welfare.

Unfortunately, willingness to pay cannot be taken as a reasonable proxy for contribution to welfare if similar individuals face the choice with very different endowments. Congestion pricing is a reasonable candidate for near-optimal policy in a world where consumers are roughly equal in wealth and income. The more unequal the population of consumers, the weaker the case for price rationing. Schemes like congestion pricing become impossibly dumb in a world where a poor person might be rationed out of a life-saving trip to the hospital by a millionaire on a joy ride. Your position on whether congestion pricing of roads, or many analogous price-rationing schemes, would be good policy in practice has to be conditioned on an evaluation of just how unequal a world you think we live in. (Alternatively, maybe under some “just desserts” theory you think inequality of endowment in the context of an individual choice is determined by more global factors that justify rationing schemes that are plainly welfare-destructive and would be indefensible in isolation. I, um, disagree. But if this is you, your case in favor of microeconomic market-clearing survives only through the intervention of a very contestable macro- model.)

Inequality’s evisceration of the case for market-clearing does not require any conventional market failures. We need not invoke externalities or information asymmetries. The goods exchanged can be rival and excluded, the sort of goods that markets are presumed to allocate best. Under inequality, administered prices might be welfare maximizing when suppliers are perfectly competitive (a price floor might be optimal) or when demand is perfectly elastic (in which case price ceilings might of help).

But this analysis, I can hear you say, cruel reader, is so very static. Even if the case for market-clearing, or price-rationing, is not as strong as the textbooks say in the short run, in the long run — in the dynamic future of our brilliant transhuman progeny — price rationing is best because it creates incentives for increased supply. Isn’t at least that much right? Well, maybe! But there is no general reason to think that the market-clearing price is the “right” price that maximizes dynamic efficiency, and any benefits from purported dynamic efficiency have to be traded off against the real and present welfare costs of price rationing in the context of severe inequality. It’s quite difficult to measure real-world supply and demand curves, since we only observe the price and volume of transactions, and observed changes can be due to shifts in supply or demand. To argue for “dynamic market efficiency” one must posit distinct short- and long-run supply curves, a dynamic process by which one evolves to the other with a speed sensitive to price, and argue that the short-term supply curve over continuous time provides at every moment prices which reflect a distribution-sensitive optimal tradeoff between short-term well-being and long-run improved supply. If not, perhaps a high price floor would better encourage supply than the short-run market equilibrium, at acceptable cost (as we seem to think with respect to intellectual property), or perhaps a price ceiling would help consumers at minimal cost to future supply. There is no introductory-economics-level case to establish the “dynamic efficiency” of laissez-faire price rationing, and no widely accepted advanced case either. We do have lots of claims of the form, “we must let XXX be priced at whatever the market bears in order to encourage future supply”. That’s a frequent argument for America’s rent-dripping system of health care finance, for example. But, even if we concede that the availability of high producer surplus does incentivize innovation in health care, that provides us with absolutely no reason to think that existing supply and demand curves (which emerge from a crazy patchwork of institutional factors) equilibrate to make the correct short- and long-term tradeoffs. Maybe we are paying too little! Our great grandchildren’s wings and gills and immortality hang in the balance! Often it is simply incorrect to posit long-term price elasticity masked by short-term tight supply. The New Urbanists are heartbroken that, in fact, the supply of housing in coveted locations seems not to be price elastic, in the short-term or long. Their preferred solution is to cling manfully to price rationing but alter the institutions beneath housing markets in hope that they might be made price elastic. An alternative solution would be to concede the actual inelasticity and just impose price controls.

But… but… but… If we don’t “let markets clear”, if we don’t let prices ration access to supply, won’t we have day-long Soviet meat lines? If the alternative to price-rationing automobile lanes creates traffic jams and pollution and accidents, isn’t price-rationing superior because it avoids those costs, which are in excess of mere lack of access to the goods being rationed? Avoiding unnecessary costs occasioned by alternative forms of rationing is undoubtedly a good thing. But bearing those costs may be welfare-superior to bearing the costs of market allocation under severe inequality. There is a lot of not-irrataional nostalgia among the poor in post-Communist countries for lives that included long queues. And there are lots of choices besides “whatever price the market bears” and allocation by waiting in line all day. Ration coupons, for example, are issued during wartime precisely because the welfare cost of letting the rich bid up prices while the poor starve are too obvious to be ignored. Under sufficiently high levels of inequality, rationing scarce goods by lottery may be superior in welfare terms to market allocation.

The point of this essay is not, however, to make the case for nonmarket allocation mechanisms. There are lots of things to like about letting the market-clearing price allocate goods and services. Market allocations arise from a decentralized process that feels “natural” (even though in a deep sense it is not), which renders the allocations less likely to be contested by welfare-destructive political conflict or even violence. It is not market-clearing I wish to savage here, but the inequality that renders the mechanism welfare-destructive and therefore unsustainable. Under near equality, market allocation can indeed be celebrated as (nearly) efficient in welfare terms. However, if reliance on market processes yields the macroeconomic outcome of severe inequality, the microeconomic foundations of market allocation are destroyed. Chalk this one up as a “contradiction of capitalism”. If you favor the microeconomic genius of market allocation, you must support macroeconomic intervention to ensure a distribution sufficiently equal that the mismatch between “surplus” and “welfare” is modest, or see the balance tilt towards alternative mechanisms. Inequality may be generated by capitalism, like pollution. Like pollution, inequality may be necessary correlate of important and valuable processes, and so should be tolerated to a degree. But like pollution, inequality without bound is inconsistent with the efficient functioning of free markets. If you are a lover of markets, you ought wish to limit inequality in order to preserve markets.

Update History:

- 14-May-2014, 1:50 a.m. PDT: “wholly unjustifiable

conceptualslip between the two concepts.” - 14-May-2014, 12:25 p.m. PDT: “absolutely no reason”, thanks Christian Peel!

- 3-Aug-2014, 10:50 p.m. EEDT: “and

log-runlong-run supply curves” - 23-Mar-2021, 1:40 p.m. EDT: “…people derive

thesimilar but steadily declining…”; “TheyThe greater the macro- inequality, the less persuasive the micro- case…”

Will there be a review of Piketty’s K21 and the phenomenon? This post seems sort of a bank shot/knight’s move on themes and problems the book brought up. Like “Fudging aggregation is at the heart of economic instruction,” and the production function. And a capitalism that generates inequality (unless there’s war and crisis).

The traffic congestion pricing example reminds me of the Supreme Court’s “money is free speech” argument regarding campaign finance legislation.

May 14th, 2014 at 9:35 am PDT

link

So, you start out by sneeringly dismissing a central moral insight, namely that interpersonal utility comparisons are morally and philosophically suspect at best. (I can’t speak for others, but for me the best one-sentence statement of why I am a libertarian is “people are not equal, they are incomparable”). Then you construct a Rube Goldberg version of the standard diminishing-marginal-utility case for redistribution, which is just what that same insight undermines. It’s a pretty game from a certain angle, but it’s a game.

Fuck your collectivist, egalitarian, nonsense definition of “welfare maximization”, and fuck your blithe willingness to trample on the liberty of your betters to truck and barter in the name of collective welfare.

May 14th, 2014 at 10:17 am PDT

link

@Nicholas Weininger

When faced with a cogent and fully coherent dismantling of a certain fundamentally flawed belief system, the only response is to dismiss that response as “Rube Goldberg,” not to point out where it’s broken. (It’s not.)

Speaks volumes. Hands over ears, eyes scrunched shut, “wah wah wah wah wah, I can’t HEAR you…!”

May 14th, 2014 at 10:41 am PDT

link

we will adopt a very conventional utilitarianism, which assumes that people derive the similar but steadily declining welfare from the wealth they get to allocate.

In other words, a) you don’t understand what welfare means and b) you don’t understand why we study it.

Welfare is not supposed to measure “utility” (whatever that means, which is whole ‘nother issue). It is supposed to measure *forgone opportunities to make everyone better off*.

If I adopt a policy that costs Bill Gates a dollar and enriches a homeless mother of four by 96 cents, you might well argue that I’ve increased total utility (provided you’ve got some coherent theory of what that means, which well you might). But I’ve still missed an opportunity to make everyone better off — that is, what I *should* have done, instead of adopting this policy, is look for a different policy that takes 99 cents from Bill and transfers 97 cents to that homeless mother, or better yet, takes 98 cents from Bill and transfers 98 cents to her.

Perhaps I won’t be able to design such a policy. But the whole point of welfare economics is to tell me when it’s worthwhile to *look* for such a policy. The bigger the deadweight loss — that is, the bigger the gap between what my policy costs Bill and the amount it benefits the mom — the more worthwhile it is to search for alternatives.

Note that you cannot do this sort of calculation with utility, because utility, unlike dollars, is not transferable.

I teach my principles students about welfare and I teach my more advanced students about utility. They’re both useful concepts with lots of implications for economic policy. But they address different questions, and each is well suited for the questions it’s designed to answer.

The big mistake is to confuse them, thinking that one can do the work of the other. That, I’m afraid, is what you’ve done.

May 14th, 2014 at 10:41 am PDT

link

@Steve Landsberg:

I can tell you do a spectacular job of indoctrinating your students into the price-theory/revealed-preferences shell game, wherein absolute/cardinal utility (because it cannot be measured) does not exist. A game in which even extreme concentrations of wealth and income not only don’t matter, but can’t matter.

It’s an utterly brilliant piece of logical, rhetorical, and political legerdemain, which has only become more effective with its endless obfuscatory embellishments over the decades.

The whole thing makes Soviet-era propaganda look foolishly, childishly crude and heavy-handed by comparison. I have to admit to being rather breathless with admiration at its sophistication and successful self-cloakery.

May 14th, 2014 at 11:15 am PDT

link

@Steve Landsberg

Why do let a (expletive deleted) like you loose of students?

“But I’ve still missed an opportunity to make everyone better off — that is, what I *should* have done, instead of adopting this policy, is look for a different policy that takes 99 cents from Bill and transfers 97 cents to that homeless mother, or better yet, takes 98 cents from Bill and transfers 98 cents to her. ”

?????? When did he say he didn’t want to do that? And why is money the correct measure here? (And I would love to hear what you think “welfare” in fact means.)

May 14th, 2014 at 11:55 am PDT

link

Landsberg is right in so far as neoclassical demand and supply curves are derived from utility curves, their intersection will be the point of maximum welfare by definition. The convex utility curves are already build into the graph.

Of course this just shows how the neoclassical approach is fundametally ideologically driven. The real world market clearing price is the a priori the welfare maximizing price. There is no need for any observation to confirm this.

May 14th, 2014 at 12:59 pm PDT

link

You mentioned that real costs curves don’t always have the “classic” shape. I don’t know whether you’ve seen Ales Lenchner’s post:

http://curiousleftist.wordpress.com/2013/11/29/debunking-economics-part-3-5-the-real-shape-of-the-average-cost-curve/

“The overwhelmingly bad news here (for economic theory) is that apparently, only 11 percent of GDP is produced under conditions of rising marginal cost […]

Firms report having very high fixed costs – roughly 40 percent of total costs on average. And many more companies state that they have falling, rather than rising, marginal cost curves. While there are reasons to wonder whether respondents interpreted these questions about costs correctly, their answers paint an image of the cost structure of the typical firm that is very different from the one immortalized in textbooks.”

May 14th, 2014 at 1:46 pm PDT

link

I refer to this issue as efficiency (from Pareto) versus optimality (from Mirrlees). There are two frontiers–the Pareto frontier is the set of all allocations that have no deadweight loss associated with them for some set of Pareto weights on individual utilities, and the Mirrlees frontier is the set of all points that maximize weighted average utility for some set of Pareto weights. Generally, the two overlap for some range of (roughly equal) initial distributions. But at the extremes they will differ–it is actually optimal to allow some amount of inefficiency.

Of course, that is all about issues arising from the initial distribution of wealth. Even ignoring issues of optimality, maximizing surplus isn’t necessarily efficient–to claim that it is you also need to assume that the trades themselves have negligible wealth effects. It’s typical to address that problem by using “hicksian” demand curves, but for non-standard preferences even that doesn’t necessarily work because individuals can be highly heterogeneous not just in their initial wealth, but in the magnitude of the wealth effect of a certain transaction (“one man’s trash is another man’s treasure”). That is, redistribution between agents can be welfare-improving even if everyone is equally wealthy to begin with, and even if those transactions would not happen without intervention.

May 14th, 2014 at 2:03 pm PDT

link

I don’t think your price ceiling analysis is deep enough. The producers who do best will be the ones who can operate with the lowest costs. But suppose I’m a poor person who *could* produce at higher cost? For example, I have a spare room that I can rent, provided the rent is higher than my insurance. I would be locked out of the market due to the price ceiling. In contrast, the rich building developer who can amortize his expenses over more apartments would be able to compete at a lower price. Even in a world of high inequality, price ceilings can be trouble.

I think the biggest take-away from the post is “there is a lot we don’t know”. Do poor people have less access to entertainment in a world with high inequality? Less information? Fewer drugs? Worse clothing? It all depends on the particular counter-factual that you compare it to.

May 14th, 2014 at 2:36 pm PDT

link

The rollback of net neutrality would be another example along the lines of traffic congestion pricing.

May 14th, 2014 at 4:46 pm PDT

link

OK, so basically your whole argument is that a Pareto efficient market is not necessarily social welfare maximizing (this is Econ 101 if you consider the simplest case of externalities). So yeah, so far I’m with you.

The huge mistake you make is defending bad policies which distort markets. I mean, come on… you’re defending rent control and lack of congestion pricing on grounds of equitable access, and in the process you’re justifying insufficient housing and insufficient infrastructure investment. Follow the second fundamental theorem of welfare economics: you can create any pareto optimal result you want with endowment redistribution. Progressively tax consumption, sure, or institute a Henry George tax, but don’t willfully distort market clearing for equity’s sake.

Ugh.

May 14th, 2014 at 5:27 pm PDT

link

“But the goal of market exchange is to maximize welfare, not to generate trade for the sheer churn of it.”

Would it safer to say that, in reality, (open) market exchange facilitates an improvement of welfare through trading something you want (slightly) less than something you can get through the exchange? Maximization may happen along some sort of theoretical efficient frontier, but in general you trade what you have for what’s available.

May 14th, 2014 at 6:53 pm PDT

link

SRW is treating the inequality as exogenous, isn’t he?

To the extent that inequality results from government failure of one kind or another, of course a government intervention to curb its side-effects will be desirable but ex hypothesi infeasible or very difficult. To the extent that it results from market exchange, I’m not happy about its consequences, but I don’t feel much like doing anything about them either, and I expect the people I’m “trying to help” will not thank me.

Yes, I can see these two alternatives are not exhaustive, but I’m not quite sure what I’m missing.

May 14th, 2014 at 9:30 pm PDT

link

This was one of your best posts in a while. Great analysis and the best framing of the problem of inequality I’ve come across since it became the topic of the day. Nothing to add here, except thanks!

May 14th, 2014 at 10:11 pm PDT

link

The distinction between consumer surplus at the individual and community level, based on differences in the marginal utility of money, is very carefully explained (step by step) in my introductory micro text, which should hit the streets very soon. (I just finished reviewing the proofs.) I don’t go as far as SRW in asserting a monotonic relationship between income and MU of money. (I accept that there are idiosyncratic differences that may or may not wash out, depending on the context.) Anyway, if you care about these sort of things, you might want to take a look.

As for myself, I no longer believe in “utility”. At all. And I think the urge to have a set of tools that simultaneously do positive and normative work is the core problem. What best explains how the world works is not what best explains whether we should approve of it or not–if in fact we should even have such a normative theory in the first place. However, I left my personal views out of the textbook; it’s an introduction to economics as it actually is, not dormanomics as I’d like it to be.

May 14th, 2014 at 10:43 pm PDT

link

I don’t know about the policy implications, but a clearly written and very interesting post to read – thanks

May 15th, 2014 at 1:27 am PDT

link

A L @12:

“OK, so basically your whole argument is that a Pareto efficient market is not necessarily social welfare maximizing”

Be careful what you mean by “a Pareto efficient market”. The unregulated market is just one particular Pareto efficient outcome out of many.

“this is Econ 101 if you consider the simplest case of externalities”

In this post, externalities aren’t considered. They don’t need to be.

” Follow the second fundamental theorem of welfare economics: you can create any pareto optimal result you want with endowment redistribution.”

I’d find it easiest to just refer you to this post and the comments that follow it (http://mainlymacro.blogspot.com/2014/05/pareto-inequality-and-government-debt.html). If you disagree with my objections to the way pareto optimization is abused in economics, it would be great if you could explain why there as well as here, as defenders of Pareto optimality and the relevance of the second welfare theorem were conspicuously absent and it’s more on-topic there than here.

To apply my objections to this specific case: SRW has provided an argument that in an ideal perfectly competitive market, price controls may be preferred to the unfettered market. You reply that price controls are bad because there is an even better third option out there. Assuming you are right, this in no way argues against SRW’s point that price controls can be better than the unfettered market. Also, your argument requires bringing macrofoundations into micro which illustrates SRW’s other point.

But we don’t need to assume you’re right about the second welfare theorem. Pareto optimization arguments tend to pit the theoretically possible against the practically possible to discard the latter from consideration. It turns out it is a whole lot easier to build a political movement around raising the minimum wage than a Henry George tax. (Is that Pareto efficient anyway? Any tax scheme is going to have incentive effects that the second welfare theorem assumes away.) So do we throw away ideas that are easy to explain, legislate, build support for and enact that we believe will generally improve things if there are options which will never happen that would in theory improve things even more?

May 15th, 2014 at 2:58 am PDT

link

[…] at 3:16 on May 15, 2014 by Mark Thoma Should markets clear? – interfluidity Why inequality lowers social mobility – Miles Corak How the euro changed international debt […]

May 15th, 2014 at 3:16 am PDT

link

A lot of people here are missing something. Our host is making a SECOND BEST argument. Arguing that redistribution is better than interfering with markets is besides the point.

May 15th, 2014 at 3:36 am PDT

link

“To the extent that it results from market exchange, I’m not happy about its consequences, but I don’t feel much like doing anything about them either, and I expect the people I’m “trying to help” will not thank me.”

You think impoverished people won’t thank you, if you give them money? Do you look that sinister?

May 15th, 2014 at 3:41 am PDT

link

I also wonder whether even if everyone was equally well off, food rationing would still be the only option in the peculiar situation of a shortage due to something like a war time blockade. Basically every person has the same need for food. In no sense do flexible prices help to ensure that food gets distributed to those that have more need for it. Supply can not be increased (that is what defines the situation). What actually happens, if there is not rationing, is panic buying and hoarding with some people consequently starving whilst food hoards spoil and go to waste. The more ludicrously high the price of food becomes, the more desperate the panic and so the more extreme the tragedy becomes.

That was exactly the scenario that killed millions in the Bengal famine of 1943 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bengal_famine_of_1943. The Churchill government provided us with a side by side comparison of WWII food rationing in the UK with no real hunger versus no such food rationing in India and so three million entirely avoidable deaths from starvation.

May 15th, 2014 at 5:40 am PDT

link

I found your argument very compelling, but I have a few issues with your characterization of the “New Urbanist” arguments about increasing density. First, a side note – none of the three linked authors should be labelled “New Urbanists”. New Urbanism is an urban design and development movement, not an economic school, though they may share some overlapping beliefs.

Second, you mischaracterize the argument for more density by presupposing an inelastic housing supply and then arguing that any attempts to modify the ‘institutions’ beneath housing supply would impose the same sort of inequitable outcome as your other examples, such as congestion pricing. But in reality, an inelastic housing supply is an artificial intervention in the housing market, and the institutions (such as zoning, minimum parking, etc) are themselves causing the inequitable outcome, decreasing the overall welfare. These institutional limitations on supply are precisely what allow the rich to purchase the entire supply of housing in a neighborhood and price everyone else out.

So, while I agree with you that price rationing breaks down under conditions of inequality, it is clear that certain alternatives (such as the price floor imposed by housing supply limitations) reduce welfare far more than unfettered price rationing.

May 15th, 2014 at 2:53 pm PDT

link

Nice post. It’s good to see more economists taking a closer look at various assumptions about the field.

May 15th, 2014 at 10:13 pm PDT

link

Yes! Finally something about 8 ball pool iphone cheats no jailbreak.

May 16th, 2014 at 7:36 am PDT

link

[…] Should markets clear? Steve Waldman […]

May 17th, 2014 at 6:56 am PDT

link

[…] Source […]

May 18th, 2014 at 3:00 am PDT

link

[…] 2014 at 18:43:42 EDTTo: dewayne@warpspeed.comShould markets clear?By Steve WaldmanMay 14 2014<http://www.interfluidity.com/v2/5117.html>David Glasner has a great line:[A]s much as macroeconomics may require microfoundations, […]

May 18th, 2014 at 8:07 am PDT

link

Nicholas Weininger demonstrates that extreme-right-wing so-called “libertarians” are really nothing more than hate-filled class bigots and neo-fascist types.

May 18th, 2014 at 1:15 pm PDT

link

SRW, there is an important assumption in the S&D diagram as drawn. It pictures the q-suppliers (sellers) and m(oney)-suppliers (buyers) as equal in bargaining power. If they were unequal the slopes or positions of one or the other or both lines would be different. The fact that the S&D curves are at right angles to one another and both intersect a corner demonstrates the equal power distribution. Furthermore, so drawing the curves gives them two peculiar properties: 1) the revenue (pq), which can also be expressed as the suppliers cost plus the suppliers surplus (profit) just happens to equal the consumers’ surplus and 2) this revenue or total surplus area is represented by a square and so is at a maximum.

This S&D curve represents an idealized “perfectly competitive” market, where all sellers and all buyers are price takers. Who then are the price makers? Usually dealers, who take a large part, if not all, of the surplus. Theoretically, both sellers and buyers could be better off under perfect competition, if indeed they did split the surplus. Usually, in the real world neither have much or any bargaining power, which is predominantly in the hands of dealers or traders or merchants or employers or bankers or. . .

It’s always interesting to ask “Who has the power? How is it exercised? How is it justified (or concealed)?”

May 18th, 2014 at 1:31 pm PDT

link

Hat’s off to economists who explain how classical / mainstream economics is wrong in terms of their own internal assumptions and start points. Your post is an excellent critique of some of their assumptions.

But a couple of points I quibble with that you stated:

“Since a trade requires a willing buyer and a willing seller…” – aahhh, yes. But a trade in the real world often doesn’t have a “willing” participant. Often the buyer or seller is “forced”, so demand, supply, and so, price, is not optimal for the maximum welfare.

Second, “But the goal of market exchange is to maximize welfare, not to generate trade for the sheer churn of it.” – hahahaha, two words: Wall Street. That is exactly their idea; no welfare, just trading for the sheer churn of it.

Really, the above two points really show the dysfunction of main stream economics, no modern system (or any decently complex society) is based only on a producer and a consumer. Most societies are based on tri-element system – producer, consumer, and rule maker. The rule maker is the government and its functions of building the web of legal and monetary (money!) rules that the producer and consumer operate within.

May 19th, 2014 at 2:52 am PDT

link

[…] Randy Waldman has a good post which is nevertheless completely wrong. I’m normally a fan of interfluidity, so I feel […]

May 19th, 2014 at 3:55 pm PDT

link

Is commenting in previous posts disabled?

In relation to your minimum income post I’m a big fan of minimum income for the reasons you cite. But I don’t think it will effect things much. The kind of people that want to do work on their own, and whose skills are useful in the current (and future) economy, are generally high IQ people often from good families who aren’t really worried about material destitution. To the extent they make decisions for money it usually relates to three things:

1) Health Expense, which is a different problem from minimum income

2) High COL in high status cities with opportunities, and by definition minimum income won’t be enough to live in these cities unemployed since it will have to be something below the national median (in addition, many of these people already have the parental resources to be subsidized a bit after college if they want to try and make it big).

3) Competition for status and mates. Most of these people your talking about feel like they need upper middle class jobs at some company in order to have the social status they need and be desirable enough to the opposite sex. Minimum income will still leave them low status and undesirable in their peer group. To the extent it makes competitors lower down the ladder more competitive in the social and sexual marketplaces it actually places more pressure on them to take the safe UMC employment route to compete.

May 20th, 2014 at 3:01 pm PDT

link

In conclusion, we must destroy the market in order to save it.

Fire up the choppers and plot vectors for healthcare, housing and education.

They’ll thank us some day…

May 21st, 2014 at 11:59 pm PDT

link

When you talk about congestion pricing, you assume that we are not already in the position “where a poor person might be rationed out of a life-saving trip to the hospital by a millionaire on a joy ride.” Charging a market-clearing price for access to the Manhattan commons would not initiate the process of rationing – it would replace the current system of rationing, which is nearly impossible to defend. The roads are simply not fully functional with current levels of traffic, whether the user is a person with a rational and ethical need for road use or a person with the means and desire to pay a high price for road use for personal enjoyment. Further, the roads aren’t free and current prices are a real burden on the working poor and those in emergency situations. Further, much of the use that the system accommodates is the equivalent of millionaires on joy rides – Midtown workers taking cars home based on their desire to avoid the slow breakdown of the city’s transit infrastructure (although admittedly we have not dropped back to ’70s-’80s levels), wealthy townhome residents ordering groceries delivered to their front door by giant trucks to avoid mingling with the plebeians at the neighborhood market two blocks from their front door, and the misguided offspring of New Jersey doctors and lawyers cavorting around downtown in limousines. If we raised prices, we might prevent some of this use, and perhaps we could return to usable roads. Even if higher prices just collected revenue, that revenue could subsidize whatever you deem to be high-value activity. It’s not as if the poor have decent access to their city’s roads or are cost-free to the city’s wealthy residents under the status quo or any other reasonably likely alternative.

May 22nd, 2014 at 9:03 am PDT

link