K is not capital, L is not labor

Garett Jones wonders why a standard result in economics is not more widely entrenched, both in policy conversations and conventional wisdom:

Chamley and Judd separately came to the same discovery: In the long run, capital taxes are far more distorting that most economists had thought, so distorting that the optimal tax rate on capital is zero. If you’ve got a fixed tax bill it’s better to have the workers pay it…

Why isn’t Chamley-Judd more central to economic discussion? Why isn’t it part of the canon that all economists breathe in? Why isn’t it in our freshman textbooks?… The result can’t be waved away as driven by absurd assumptions: It’s not too fragile, it’s too solid…

Good economic policy doesn’t try to do things that are impossible. And if the world works roughly the way Chamley and Judd assume it does, a long run policy that redistributes total income from capitalists to workers is impossible.

So, the quick answer, obviously, is that those of us who support redistributive taxation don’t believe that the world works in the way that Chamley and Judd assume. It is very clear that Jones (who is an unusually insightful guy) doesn’t believe in a naïve mapping between real economies and Chamley-Judd-ville. See the “bonus implication” in his handout on the subject.

To annihilate in broad brush strokes, there is little reason to accept the Ramsey model, upon which the Chamley-Judd results are built, as a sufficient description of the macroeconomy. [1] Some economists might argue that it’s a decent workhorse “asymptotically”, as a means of thinking about some long-term to which economies converge. But that’s a conjecture without evidence. Actual experience, as people as diverse and diametric as Scott Sumner and J.W. Mason point out, suggests that “demand-side dynamics” may overwhelm the bounds of a hypothetical production function in determining the actual behavior of the economy, over periods of times as long as we can plausibly claim to foresee. Redistributive taxation, or tolerance of redistributive inflation in the face of poor real-economic performance, may be prerequisite to maintaining production along the sort of path the Ramsey model presumes is automatic. These possibilities, along with any form of uncertainty, are invisible to the work of Chamley and Judd. They are simply omitted from the model.

But let’s be generous. Let’s put very broad objections aside, and understand the world in Chamley-Judd terms. In practice, what does the Chamley-Judd result suggest about policy?

First, it’s worth pointing out that Jones has overstated things a bit when he claims that the Chamley-Judd result is “not too fragile, it’s too solid”. As far as I can tell [2], the optimality of a zero capital tax rate is in fact a “knife-edge” result with respect to returns-to-scale of the production function. If returns to scale are decreasing or increasing, the optimal capital tax rate from workers’ perspective may be positive or negative, and is sensitive to details. A stable, constant-returns-to-scale production function may be attractive for reasons of convention and convenience, but it is unlikely to be true. Once we admit this, we really don’t know what the optimal tax rate is in an otherwise Chamley-Judd world.

But I promised to be generous. So let’s assume that the economy is characterized by a permanent two-factor, constant-returns-to-scale production function. The Chamley-Judd claim is that it is optimal that one of these factors should be taxed and the other not be. For this to be true, there must be some asymmetry: Factor one, which we’ll call K, must be different from factor two, which we’ll call L. What distinguishes these factors and leaves one optimally taxed, the other optimally untaxed? Fundamentally, the difference is that capital accumulates, while labor does not. Judd assumes completely inelastic labor provision, Chamley allows for a labor/leisure trade-off bounded by a fixed number of hours. Each period labor is born anew, while capital stands on the shoulders of its ancestors. This difference is what drives the asymmetry and then the result. Labor is a factor in strictly limited supply, capital is a factor whose quantity can grow indefinitely and which augments labor in production. Under these circumstances, the way to get a big, rich economy — and to maximize the marginal product of labor! — is to encourage the accumulation of capital. Encouraging labor provision directly can’t take you very far, because there is a ceiling. But the sky’s the limit with capital. Further, in Chamley and Judd, nonconsumption automatically implies useful deployment of capital into production.

If these were adequate characterizations of capital and labor, the Chamley-Judd result would be much more plausible than it is. But these are very poor descriptions of the real world phenomena we ordinarily label “capital” and “labor” when we decide how much to tax them.

Let’s talk first about “labor”. As Jones hints in his “bonus implication”, labor is not in fact measurable in terms of homogenous hours. What a brain surgeon can do with an hour is very different from what a child laborer can accomplish. Macroeconomically, our collective capacity to produce improves. You might, as Jones does, refer to this incorporeal je ne sais quoi that enhances labor over time as “human capital”, or as labor-augmenting technology. Like physical capital, it seems to accumulate. In empirical fact, “human capital” and its more sociable, incorporeal twin “institutional capital” seem to be much more important predictors of the growth path of an economy than physical capital. Europe and Japan bounce back quickly after war devastates their infrastructure. But imagine that a Rapture clears the Earth and pre-agrarian nomads take possession of perfect gleaming factories. I think you will agree that production does not recover so fast. Human and institutional capital dominate physical capital. [3]

Like physical capital, and unlike hours of the day, the collective stock of human capital grows over time, without obvious bound. Yet, at least under existing arrangements, we have no means of distinguishing between “returns to human capital” and “wages”. “Capital taxation”, in conventional use, refers to levies on capital gains, dividends, and interest. As a political matter, results like Chamley-Judd are often used to support setting these to zero. But eliminating conventional capital taxes shifts the cost of government to wages, which include returns to human capital. If human capital accumulation is as or more important than other forms of capital accumulation, and if the quality of effort that people devote to building human capital is wage-sensitive, then taxing wages in preference to financial capital may be quite perverse. Further, while physical capital grows by virtue of nonconsumption, it seems plausible that human capital development is proportionate to its use, which would render a tax penalty on “wages” particularly destructive. Fundamentally, Chamley-Judd logic suggests that we should tax least the factor most capable of expanding to engender economic growth. You don’t have to be a new-age nut to believe that human and institutional development, which yield return in the form of wages, may well be that factor. It is perfectly possible, under this logic, that the roles of capital and labor are reversed, that the optimal tax on labor should be zero or even negative, because returns to physical and financial capital are so enhanced by human talent that even capitalists are better off paying a tax to cajole it.

So labor is more capital-like than a naive application of Chamley-Judd would assume. But that’s not all. What we conventionally call “capital” looks very little like the commodity in the models. In the models, there are no financial assets. Capital is crystallized nonconsumption, a real resource which is automatically deployed into production if it is not consumed.

In reality, people forgo consumption by holding financial claims. There is no clear relationship between financial asset purchases and the organization of useful resources into production. Many financial assets are claims against the state which fund current government spending. Are those expenditures “investment” in the Ramsey sense? Maybe, partially, but not clearly. Financial claims can fund consumer loans. Does financing a vacation contribute to the permanent capital of the nation? Maybe — perhaps vacationers are in fact far-sighted investors, whose labor productivity and future wages will be enhanced by a recreative break. But, maybe not. It is not at all clear. Empirically, the relationship between the outstanding stock of financial claims and anything recognizable as productive capital is very weak. [4] Finance is not an inconsequential veil over real production. It is its own messy thing.

Let’s approach the mess more analytically. In the models, foregone consumption and productive investment are inseparable. In the real world, purchasing a financial asset (or holding money!) does imply that some agent forgoes consumption. But it does not imply that the foregone consumption will be invested. The consumption an agent forgoes may be consumed by others. It may be wasted. Identities like S = I don’t help us, they just insist that we call purchases of financial assets “investment”, and then account for eventually fruitless claims via revaluation. In real life, there are a lot of those revaluations, and no measure of observable capital corresponds with a cumulation of financial savings. So, if we want to take Chamley-Judd reasoning seriously, we oughtn’t set tax rates capital gains, dividends, or interest to zero. Instead, we should ensure that real investment activity by firms is tax advantaged. There is no Chamley-Judd case for not taxing the interest on consumer loans or government bonds that finance transfers. There may be a case for policies like accelerated depreciation of fixed capital or even tax credits for education expenses. [5] But given the weak relationship between financial assets and real investment, eliminating conventional “capital taxes” just subsidizes the products of the financial sector. It offers a windfall to financiers and their best customers, but creates no foreseeable “piece of a bigger-pie” benefit for the people to whom the tax burden is shifted.

One final point: The force that drives the Chamley-Judd conclusion is the long-term elasticity of capital provision to interest rates. The intuition is that capitalists make a decision about whether to forego consumption and contribute to growth or whether to consume today based on a comparison between available returns and their time preference. Lower capital taxes keep returns higher and make contributing capital “worth the wait” over a longer arc of the production function, leading to a higher steady state.

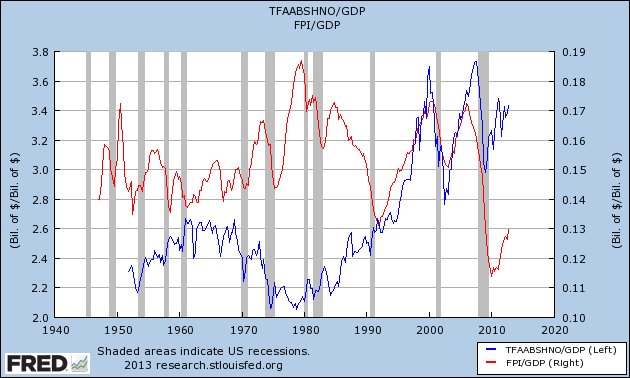

Unfortunately, this sort of calculation does not seem to describe economy-wide savings behavior very well. Aggregate purchases of financial assets seem to be insensitive to returns. In the US, yields on debt, risk-free, corporate, and individual, have been falling since the 1980s, while the stock of financial assets held by households (as a share of GDP) has grown inexorably. (Total equity returns were high only in the 1990s; financial holdings grew about as fast during the low-debt-yield, low-return pre-crisis 2000s as they did in the 1990s, see the graph below.) Unless you posit a peculiarly declining time preference, the core implication about aggregate savings behavior in any Ramsey model seems quite false. We need other stories. I have some! Perhaps consumption is approximately satiable, and the fraction of income saved is just a residual, the difference between income and the satiation level. Perhaps wealthier households save, not to endow future consumption, but because they are in a competitive race with other households for insurance or status that derive from financial holdings. Perhaps for the US, aggregate saving is largely a residual of other countries’ return-insensitive economic policy (Asian mercantilism, petrodollar recycling, etc.). In any of these cases, we’d expect gross financial saving not to be especially sensitive to investment returns. Now human capital formation may be less wage-sensitive than we’d guess too. Maybe we become brilliant more because of expectations and support provided by the people and institutions that surround us than because of the extra money we anticipate. But all these uncertainties undermine the Ramsey/Chamley/Judd edifice, rather than suggesting a zero capital tax.

There are lots of more narrow rebuttals of Chamley-Judd. Jones links Matt Yglesias and Piketty and Saez on the ways the tax result changes if you replace infinite-lived consumers with overlapping generations of people who die. The Chamley-Judd result goes away when labor markets are imperfectly competitive, when economic outcomes are uncertain, when savings are sufficiently return inelastic. Also, see Andrew Abel. To dismiss these critiques as “exotic” is to dismiss reality as exotic, and to rely without evidence on an extreme simplification of the world.

But more fundamentally, what we mean in life and politics by “capital” and “labor” are simply not the phenomena that Chamley or Judd (or Ramsey) model. It is wonderful for Jones to remind his students that, especially in a context of full employment, “capital helps workers”. Stories of what a worker can accomplish with a bulldozer versus a shovel are important and on-point. Students should inquire into the process by which in some times and places construction workers get bulldozers and live well, while in other times and places they work much harder with shovels yet barely subsist.

But Chamley-Judd tells us very little about the tax rate appropriate to income from dividends, interest, or “capital gains” in the real world. How and whether an incremental purchase of financial claims contributes to growth or helps workers is a complicated question, one that a Ramsey model can’t resolve. Models that are more realistic about finance, whether Keynesian or monetarist, predict states of the world where financial capital formation is harmful to real economic performance. To the degree that human and institutional capital grow with use rather than disuse, shifting the burden of taxation from financial claims to labor may be harmful over a very long-term. In the asymptotic steady state, who knows? We have as much reason to believe that you will like strawberries as we have to believe that the capital gains tax should be zero.

[1] You’ve got to love Robert Solow on this:

[I]t could also be true that the bow to the Ramsey model is like wearing the school colors or singing the Notre Dame fight song: a harmless way of providing some apparent intellectual unity, and maybe even a minimal commonality of approach [to macroeconomics]. That seems hardly worthy of grown-ups, especially because there is always a danger that some of the in-group come to believe the slogans, and it distorts their work.

[2] Please correct me if this is mistaken; it’s what I observe in simple simulations [pdf, mathematica] similar in spirit to those published by Jones. It’d take a lot more work than I’m prepared (or able) to do to demonstrate this result under the abstract frameworks of the original papers.

[3] It was Garret Jones himself who offered the single most insightful economics tweet of all time, on precisely this topic:

Workers mostly build organizational capital, not final output. This explains high productivity per ‘worker’ during recessions.

[4] Within the sphere of financial claims, the relationship is sometimes stronger: there may be a relationship between, say, the aggregate balance sheet size of the telecoms industry and fixed investment in telecoms. But the aggregate quantity of financial claims as a whole (restricted to those held by households to avoid double-counting of “pass-through” holdings) has no stable relationship to the quantity of measurable investment in the economy:

TFAABSHNO → “Total Financial Assets – Assets – Balance Sheet of Households and Nonprofit Organizations”, “FPI” → Fixed Private Investment; I should probably have included gross foreign holdings in the financial assets measure, but the series I’d need, though available in the flow of funds, seems not to be published on FRED. (It’d be Table L.106, “Rest of the World”, “Total financial assets”, Line 1 if anyone is more motivated than I am to find the full series and add it to household financial assets.)

[5] Interestingly, Andrew Abel points out that, under conventional Chamley-Judd assumptions, not worrying at all about human capital or the imperfections of finance, optimal tax policy may be to tax only capital, but to permit the ultimate in accelerated depreciation, immediate expensing of capital goods.

Update History:

- 8-Apr-2012, 4:50 a.m. PST: minor grammar fixes, missing the word “a”, missing a comma: “characterized by a permanent two-factor, constant-returns-to-scale production function”; “Factor one, which we’ll call K, must be different”

- 10-Apr-2012, 11:50 p.m. PST: Fixed misspelling of “

GarretGarett Jones”. (Many thanks to Douglas Edwards for pointing out the error.)

waldman: To dismiss these critiques as “exotic” is to dismiss reality as exotic, and to rely without evidence on an extreme simplification of the world.

—————-

Simplification for saleability.

March 18th, 2013 at 6:49 am PDT

link

[…] 6. Choosing the right seat, and does capital accumulate and labor not? […]

March 18th, 2013 at 12:11 pm PDT

link

I think the crucial point is that taxes on capital need to not be in the form of taxes on income from capital. It is essential that instead they are taxes on the asset value. Michal Kalecki made a very clear case that just such a “capital tax” (as he called an asset tax) would be the least distorting type of taxation possible. As he wrote in 1943:

“ the inducement to invest in fixed capital is not affected by a capital tax because it is paid

on any type of wealth. Whether an amount is held in cash or government securities or

invested in building a factory, the same capital tax is paid on it and thus the comparative

advantage is unchanged.”

Basically a Michal Kalecki style capital tax ensures that wealth is put to maximum use so as to get the yield to pay the tax with. In that sense it is the complete opposite of taxes on profits and capital gains that have the perverse effect of inducing wealth owners to keep resources idle.

March 18th, 2013 at 1:09 pm PDT

link

There is a presumption that ‘taxes on capital’ are taxes on capital when often they are taxes on consumption. Gains are never taxed if deferred, and once realized are often consumed, just as interest and dividends. Lack of ‘taxes on capital’ probably encourage more consumption of capital than investment.

March 18th, 2013 at 1:53 pm PDT

link

@Lord I’m not sure we’d care if, in the meantime, it were actually funding an expansion of productive capacity, rather than home mortgages minus finance’s take.

March 18th, 2013 at 3:03 pm PDT

link

Though complicated, I think you can argue that I work for an after tax $10. I invest the $10, sell at $50, and the $40 in profit has never been taxed.

So far so good.

But, after I pay the Capital gains tax on that $40, say $10, the remaining $30 is basically like my muscles, it goes out in field and labors day in day out, and the fruits of its labor, have never been taxed. Essentially my money is my muscles, so every new dollar made by my money is taxed once.

Funnily, Scott Sumner, he likes to argue “double taxation,” when confronted with the above $40 example, he doesn’t argue that I paid the tax already, he says profits like that are totally unusual, and then he assumes inflation happened, and he basically views the inflation as a tax.

Of course, he’s a guy arguing for inflation, so since he favors inflation tax, and he thinks EMH is true, so routine big gains are off the table, he comes down at “double taxation.”

Say a woman, take her income and invests it get lots of plastic surgery and that increases her income…

The investment is paying dividends, it’s hard to argue she wasn’t “saving” = investment.

Final reason I think the Capital Gains tax has to be higher: SMB revenues passthough an distort incentives.

The top 2% of SMB owners generate 50% of SMB revenue, these are a certain type of guys, from their pool of investments, ALL newco start up job growth BOOM occurs.

Like college athletes, we don’t know WHICH of these guys is going to go PRO, but we know its one of them. The thing is, these are the same guys OVER AND OVER throughout their life.

So, in a medium sized town, you’ve got a bunch of buddies you play poker, all successful SMB owners. They all decide to open a HOOTERS franchise, it goes well, maybe they open another.

The thing is, the current tax system, since they are currently getting their payday via passed through incomes tax, they have a distorted incentive to KEEP BUILDING HOOTERS.

But the town doesn’t need more HOOTERS, and hte don’t get along great anymore. And Steve, he’d like to take his tax free profits from HOOTERS and put it into his nephews 3D printing biz.

Steve is a SMB wild catting cowboy. He’s our lifetime big man on campus, who at anytime might, blow a newco right into stratosphere.

Meanwhile, in US we have 1031 rule that lets a building owner sell at profit, and if he reinvests in a new building, he pays ZERO taxes.

Obviously, we ought to be letting Steve move pre-tax income from HOOTERS to 3D printing, the moment he thinks more HOOTERS isn’t best idea.

And doing that means treating the top 2-3% of serial entrepreneur SMB owners as if they should move money freely, and only pay income tax on their consumption.

March 18th, 2013 at 3:55 pm PDT

link

@Morgan Warstler, that is why I think an all encompassing asset tax needs to replace all other taxes. We need people to be building real wealth by creating new real assets such as the new 3D printing example you gave rather than buying pre-existing assets such as the buildings example you gave. Under an asset tax, money sunk into creating a 3D printing start up would no longer be exposed to an asset tax until and only if the company took off and became worth something. A serial creator of such enterprises would constantly be building wealth in a tax free way.

March 18th, 2013 at 4:32 pm PDT

link

Neither this nor Jones go far enough.

First, both “K capital” and “L capital” – that is both software/machines/etc. and people/orgs/group-working methods, decline over time, and both can (and often are) rendered suddenly useless. NEITHER grows without bound nor accumulates endlessly. People die or leave. Machines wear out or become obsolete. Markets change. To retain their value these capacities must be maintained and renewed. That’s before we even get to growth.

Second, the “value” of some kinds of long lived (hence “capital”) goods (notably housing stock) changes in response to market demands, but often with no other particular change in nature. Over the last 20 years both the nominal and real values of my house have gone up – though it’s the exact same house. Likewise, lawyers who are as skilled today as yesterday are unemployed, machines that work as well as when brand new are obsolete – neither has fallen into decline nor disrepair – they’re just not what the market wants.

Third, a great deal of “capital activity” that is “savings” is really “financing current consumption somewhere” and only creates or maintains physical or human capacity as an incidental side effect of supporting consumption. This is, by the way, why just having everybody “save” more, or expanding social security (essentially a 100% consume it now transfer) will have no effect on the demographic issues clouding retirement. Everybody can suddenly start saving 20% of income, or we can raise the SS tax to huge levels to support much larger benefits, but there is a shortage of *real capacity* to provide product to retirees, then NO amount of distributing claims (money) to said retirees will enable them all to have comfortable lives.

So all policy questions need to focus on maintaining, growing, renewing, “capital” – as in capacity to provide product – be it car parts or manicures. It’s not about “saving” or “investment” it’s about maintaining, growing, renewing, capacity. And all such policies must embrace the disciplines of markets – because that will establish the outcomes anyway.

March 18th, 2013 at 5:26 pm PDT

link

Why is the debate about which factor of production to tax, instead of about if we should tax production vs. consumption? Isn’t a progressive consumption tax better than an income tax or a capital tax in almost every single way? Isn’t consumption a better measure of who ought to be taxed than wealth, or income, or wages, capital income? Isn’t it easier to administer a consumption tax and harder to cheat? Isn’t it less distortionary to tax a person based on final fruits of their economic activity rather than the particulars of how it was arranged and accounted for?

I don’t get it. I don’t understand why anyone, conservative or liberal or libertarian or anything else would prefer income or capital taxes over a consumption tax.

What am I missing?

March 18th, 2013 at 10:27 pm PDT

link

Scott Sumner read your post. He wrote:

“I can’t follow his post. Is he saying S doesn’t equal I? If not, precisely what is he saying? Talk about “financial investments” is extremely unhelpful. It confuses the individual with the aggregate, and it confuses financial investment with physical investment. I’m not saying he doesn’t have some good ideas (he’s very smart) it’s just that I can’t understnad what those ideas are. Maybe if I re-read it a couple times.”

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=20170#comment-235339

March 19th, 2013 at 12:43 am PDT

link

You can only tax production. Specifically, you can only tax factors of production, by taking of their production. This is because taxation is a redistribution of production, of goods and/or services.

A taxation on consumption is a fiction. It is like taxing a hole, or a landfill. Or welfare recipients. Or the idle rich. It is a useful fiction, perhaps, but a fiction, still, in that those who produce nothing cannot be taxed. Only by taking from them what has previously been produced, and given to them, can they be taxed. Thus, even when you tax assets, you tax previous production.

That being said, you want to tax capital and labor each at rates where they both grow at the same rate. This is because labor is also the ultimate market for capital. If labor is taxed at a disproportionate rate to capital, capital growth will outstrip its market, and the result is a recession. If capital is taxed at a disproportionate rate to labor, demand will grow faster than supply, and you will have inflation.

Currently, capital is not being taxed enough, labor is being taxed too much, and the result is recession.

March 19th, 2013 at 1:37 am PDT

link

[…] for 03-19-2013 Posted at 3:17 on March 19, 2013 by Mark Thoma K is not capital, L is not labor – Interfluidity Island Nightmares – Paul Krugman Will Twitter Replace RSS? – Andrew Sullivan […]

March 19th, 2013 at 3:17 am PDT

link

@greg, “If capital is taxed at a disproportionate rate to labor, demand will grow faster than supply, and you will have inflation.”

I think a lot depends on the type of capital tax. Imagine a situation where the only tax was a flat tax on all asset values (cash, stocks, real estate, bonds etc etc) and the government ran a balanced budget. Are you saying that that would lead to inflation? Where would the money come from to sustain that inflation? Why would supply not grow to meet demand? Profits and capital gains would not be being taxed. There would be no disincentive to create profitable enterprises.

March 19th, 2013 at 3:49 am PDT

link

I want to point to Lord’s comment. Yes very apposite.

My own view is that I have always been (for a left winger) a bit careful about how you go about taxing capital. It always seem to me that (real) capital is invested on the basis of after-tax returns versus risk and capital cost (interest). This also applies to human capital investment (training either on the job or in formal education). Invested in real capital (and human capital) is a good thing – something we want to encourage. At the very least, we can encourage it by making the investment itself tax free. It seems to me likely that in aggegate interest rates (and exchange rates) should adjust to offset changes in tax rates. (Why do conservatives believe monetary policy offsets fiscal policy negatively, but not positively? Blind spot?) The key variable here then is risk.

How can we reduce risk in a volatile world? This makes me think tariffs (moderate and unbiased) aren’t such a bad idea. Dare I suggests regulation and tariffs?

We already do some things to reduce risk – intellectual property rights (unfortunately badly), limited liability companies (abused via leverage) and bankrupcy laws (recently weakened). Reducing risk needs to have a higher priority and we need to think more carefully about it.

March 19th, 2013 at 4:26 am PDT

link

P.S. One policy I’m all for is that depreciation should be completely at the discretion of the tax payer. You can do it all in one go or over 100 years, whatever suits you.

March 19th, 2013 at 4:31 am PDT

link

P.P.S. One thing that seems often forgotten here is income versus susbstitution effects. Ultimately, people (not some amorphous robot like “investor”) do the investment/consumption decision based on long term income expectations. Income effects apply here too – it is not all substitution effect. What does worry me is small open countries that don’t have their own currency. In this case intercountry tax arbitrage is a major effect. I wonder why I might be thinking of that just now?

March 19th, 2013 at 4:40 am PDT

link

@9 Lawrence D’Anna

“I don’t get it. I don’t understand why anyone, conservative or liberal or libertarian or anything else would prefer income or capital taxes over a consumption tax.”

Isn’t wealth not simply deferred consumption but also in effect the power to decide whether other people sit on the sidelines? A consumption tax does nothing to address misuse of that power. Someone could amass wealth and not deploy it in any productive way. That wealth would retain its financial power but meanwhile no real means for being able to meet that future financial claim would be being maintained. Holding wealth also depends on there being a powerful state to uphold the rule of law and ensure that the financial claims keep their value. Isn’t it only just that those receiving that service pay for it?

March 19th, 2013 at 6:12 am PDT

link

@9 Lawrence D’Anna

In practice a progressive consumption probably involves measurement of income anyway (My guess is you don’t people having to give their tax number to the counterparty for every single transaction.)

Plus what stone says about wealth = power.

March 19th, 2013 at 6:39 am PDT

link

Stone,

I’m attracted in principle to a wealth tax, it has some nice features (including side effects such as discouraging speculation), but I’m not sure how in practice you would measure wealth fairly and transparently.

March 19th, 2013 at 6:42 am PDT

link

The Wiki artle on the Ramsey model contains this telling sentence,

“Originally Ramsey set out the model as a central planner’s problem of maximizing levels of consumption over successive generations. Only later was a model adopted by subsequent researchers as a description of a decentralized dynamic economy.”

March 19th, 2013 at 7:28 am PDT

link

The real value of a unit of labor increases with time. The real value of a unit of capital decreases with time. Just saying.

March 19th, 2013 at 9:41 am PDT

link

@19 reason, things such as stocks, bonds and cash are already valued, things such as real estate and collectables get valued for estate taxes at the moment. I guess the best way to contest an asset tax would be to auction off an asset and buy it back yourself at a price lower than the tax people had valued it. I think you ought to then be able to have that price as the taxable price.

March 19th, 2013 at 9:48 am PDT

link

For me, it clears up a lot of these confusing discussions to remember that K capital is essentially the leverage to solicit or command the effort of other people. As the article describes, L capital can be enhanced over time, but frankly L capital is fairly stable, maybe varying by an order of magnitude. Like food in your kitchen, it can become either a gourmet meal or swill for the hogs, but it cannot become food for 5000.

K capital, by contrast, can nominally increase without limit, because of its potential / imaginary nature. If it remains unused, there is no effect on the economy. Like the Magic Penny, “hold it tight and you don’t have any.” But judicially applied, especially ins a society where it is essential but most people don’t have much, it can leverage other people’s energies as desired.

Therefore, unlimited accumulation of K capital inevitability leads to a plutocracy.

March 19th, 2013 at 10:05 am PDT

link

stone @22. Stocks and bonds have constantly changing values. How will you define which value is to be taxed? If you define it at a particular instant of time, won’t that lead to market manipulation?

March 19th, 2013 at 10:11 am PDT

link

stone @22

“things such as real estate and collectables get valued for estate taxes”

Once in a generation. Such valuation is costly.

And there you go again introducing a complicating factor. In principle assets are already taxed in estate duties. Once at 30% every thirty years or 1% every year are not vastly different. But the costs involved are vastly different. So why not concentrate on estate duties (or better taxing inheritances as income), instead?

March 19th, 2013 at 10:15 am PDT

link

Two remarks:

(A) The classics distinguished between ‘Land’, Labor and Capital, ‘Land’ being the real factor of production which can not be increased or enhaced. The fertility of actual agricultural land of course depends on investments – but these are counted as capital, invested in the land. Compare oil and the capital used to get oil out of the ground. ‘Land’ stands for space, sun, natural resources, clean air and the like. There are reasons why neo-classicals lumped ‘Land’ and ‘Capital’ together: somebody owns the land. And the owner collects the rents. Lumping them together enables one to forget about rent incomes and treat these rents as ‘return to capital’ and to forget about ownershiprelation and their influence on the division of income. There are reasons to tax land (like a CO2 tax or a tax on the economic value of the land on which buildings are built). This is of course the Henry George/Poilitical Economy point of view (and even the Ricardian one). When you lump land together with capital you can dismiss these reasons.

(2) S=I is a national accounting identity. The part of total income which is not consumed is by definition equal to investments. When we reclassify consumer durables as investments, investment and saving will increase in the national accounts. This differs from the neo classical definition of saving: money spent on financial assets. Which, in the more extreme variants of neo classical economics is by definition equal to actual investments, which is of course not the case. Let’s call the first kind of investments ‘real investments’ and the second class ‘financial investments’. These financial investments have (borrowing the phrase of Keynes) a ‘zero elasticity of production’, i.e. it requires no effort to produce them (well, you have to make some keystrokes…). Keynes quote: “elasticity of production meaning, in this context, the response of the quantity of labour applied to producing it to a rise in the quantity of labour which a unit of it will command”. Spending on financial assets will not increase production, employment and income, spending on real investments will increase production, employment and income. We really have to start to make a distinction between real investments (in Dutch: investeringen, meaning: (0,1*potting+0,9*planting)) and financial investments (in Dutch: beleggingen, which has a positive but mainly defensive meaning which is (0,9*potting+0,1*planting); the literal translation ‘belaying’ might in fact not be too bad). And between ‘value added saving’ and ‘financial saving’.

March 19th, 2013 at 11:22 am PDT

link

In the rainbow world that I live in, strawberries are just a vehicle for cream.

March 19th, 2013 at 11:54 am PDT

link

Another comment on your post:

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=20170#comment-235398

Waldman’s article was a little bit silly. The idea of an unlimited potential human capital (no one really defines human capital meaningfully) compared to limited physical capital driving growth ignores the obvious point that increasing savings (physical capital as Waldman strangely calls it) are the only way to implement technological changes. In other words, if some genius starts inventing more productive equipment, you still need capitalists to fund the production of the new machines and the upgrading of production processes.

Also, the idea that human capital is unlimited is a strange. Sure human knowledge in totality can grow but as I mentioned before, savings is the only possible vehicle for transforming that knowledge into tangible results. Second, human characteristics are limited. Unless we start developing genetic mutations like X-Men, people can only move so quickly, learn so much, work so hard, etc.

March 19th, 2013 at 12:09 pm PDT

link

Consider the government spending constant and savings do become investments, mostly. That is, more resources are used for non-consumption. If then the government decides to spend or invest more as more savings drive down the interest rate, that means “even better” under the standard leftist assumption that the government produces more good than evil. There are also other errors in the text but also good points.

March 19th, 2013 at 12:46 pm PDT

link

reason@25, estate taxes can be evaded using trusts and such like. With an asset tax real estate would have to have the tax paid on it in order for the owner to demonstrate ownership (just as with car tax in the UK now). There would be no way of evading it. That is why it is vital that the tax burden only depends on the nature of the asset and not on the owner. With an estate tax the tax burden depends on the nature of the owner and that can be wriggled around.

Estate taxes also don’t provide a constant impetus for ensuring that wealth is constantly put to use in the way that an asset tax would. I agree that the valuation required for an estate tax would be burdensome but I’d advocate no other taxes at all. In the context of clearing off all other tax burdens, I don’t think periodic revaluations would be onerous.

reason@24 When investment funds have a management charge, they charge that as a % of assets under management. Presumably the exact same set up could be used for an asset tax charge. Most such accounts seem to get constantly valued electronically. It wouldn’t seem to me to be difficult to convert that to a tax.

March 19th, 2013 at 1:06 pm PDT

link

This is a magnificent post. No disagreements, but a couple auxiliary points.

First, this is a nice illustration of something I often argue about with more mainstream friends. Economics training focuses on the manipulation of formal models, and that’s what gets you status in the profession. But the really challenging thing in economics isn’t making the models work, but knowing how to map the models onto the real world. It’s one thing to be a virtuoso at showing formal relationships between L and K, something else entirely to know whether or to what extent “K” corresponds to the stuff we call capital in the real world.

Second, more substantively, I think this is where the heterodox vision of the world divided into capital-owners and workers has real advantages over the mainstream vision of homogeneous households. If capital-owners’ objective is to get the maximum available return on their capital, then there’s no margin between saving and consumption (or leisure) to worry about.

March 19th, 2013 at 1:15 pm PDT

link

Merijn Knibbe also makes a good point — if you took the Chamley-Judd argument seriously you’d end up with Henry George, not a pure tax on labor income.

March 19th, 2013 at 1:19 pm PDT

link

Another difference between capital and labor is that wage earners have much more practical experience and physical strength. If you were to send a large group of the wealthiest and most powerful of the capital class together with all of their cash in huge crates to a deserted island, they would enjoy little or no government interference, and absolutely no taxes. They would probably discover quite quickly how utterly dependent they are on wage earners to sustain their lifestyle. In fact capital may be much less likely to survive in a wilderness than an equivalently sized group of wage earners who are toughened by lives of hands-on physical labor and practical engineering skills.

Even if it were absolutely true that optimal economic performance could be obtained by having wage earners pay all taxes and levying zero taxes on capital, certain unanticipated externalities might creep in, like for example labor might start burning capital’s property in a rebellious rage. Capital may even start to fear for its life and decide that paying taxes really isn’t so bad after all.

March 19th, 2013 at 2:42 pm PDT

link

[…] Earthquakes and the Mind-Bending Laws of Markets (Bloomberg) • K is not capital, L is not labor (Interfluidity) • When Mom and Pops Battled Five and Dimes (Echoes) • On the Brink? China’s Solar Industry […]

March 19th, 2013 at 4:25 pm PDT

link

Stone @13 asks: “Where would the money come from to sustain that inflation?” Good question. Where did it come from for the Stagflation of the 1970’s? The M2 stock increased only a few percent per year, but inflation averaged over 7%. M2 velocity also changed very little. Government deficits did not seem to correlate. We did have the oil price shocks…

Your flat asset tax has its virtues, most particularly that it would encourage assets to be used, instead of sitting idle, as happens with the toys of the wealthy.

March 19th, 2013 at 10:48 pm PDT

link

This article is a fantastic case study in the truth of one of its key sentences:

That is, (some) economists have been indulging in the lamppost fallacy: befuddledly looking for their keys in the falsely brilliant illumination under the lamppost of an oversimplified model, rather than back in the obscure recesses of reality where they have reason to believe the keys might actually be located.

Surely it’s possible to work with more realistic models, or at least more plausible ones. If that makes the mathematics less tractable, so be it. From the original post along with Merijn Knibbe’s and J.W. Mason’s comments, it would appear to be important to distinguish among (at least) five different factors of production, of which the first three are accumulable and the last two are not:

(1) Conventional material capital other than land

(2) Individual human capital (accumulated skills and knowledge)

(3) Institutional or organizational capital (social structures in support of teamwork)

(4) Labor time

(5) Land

Note that financial “capital” is not considered to be a factor of production at all; any contribution it makes to production would have to be modeled via explicit assumptions about its use in obtaining some combination of the true factors of production through trade. With the right assumptions, the traditional perspective that all forms of capital (including financial) are effectively fungible might conceivably be justified. But that can’t be assumed from the outset, or built into the very structure of a model, without making that model effectively useless.

It would seem that at least this fine a grain of analysis is a precondition for any generally applicable model worth taking seriously. Simpler models may fit special cases.

March 20th, 2013 at 3:03 am PDT

link

The more important theoretical question is whether the Chamley-Judd result applies to the economy in which it is derived, i.e. perfect markets, constant returns, representative agent, etc.. I’m not sure that has been proved at all: the class of tax systems considered by Chamley-Judd and the welfare function used strike me as very special: to name but a few problems: time-consistency should be built in, more complicated tax schedules including randomization should be taken into consideration by the planner (see Mirlees on non-linear tax schedules and Stiglitz and co-authors on randomization), the welfare criterion should take that and more into account: in particular, a tax on the capital stock and a tax on capital income are different things not just in terms of efficiency but in terms of welfare, and so that should be built in the utility functions, oh and also the well-known fact that it all relies on separability and an Atkinson-Stiglitz type result. I think the simple fact that neither Atkinson nor Stiglitz (nor Chamley I bet) endorse a Chamley-Judd result makes the result suspicious, even within its own paradigm. I’m saying this spontaneously though, so don’t take my word for it.

March 20th, 2013 at 3:19 am PDT

link

greg@35, ““Where would the money come from to sustain that inflation?” Good question. Where did it come from for the Stagflation of the 1970′s? The M2 stock increased only a few percent per year, but inflation averaged over 7%. M2 velocity also changed very little. Government deficits did not seem to correlate. We did have the oil price shocks…”

My impression was that the oil price shocks were actually part of a much larger phenomenon of developing countries starting to compete with the developed world for getting a share of the global commodity supply. The “great moderation” was basically a way of firmly putting a stop to that by enticing capital flows into the developed world from the developing world. Just look at the wikipedia page for “economy of Nigeria” as an example (there are others across the world) of how economic growth in the developing world was rocketing in the 1970s and then went into free fall in the 1980s and 1990s. Immense amounts of money flowed from the developing world to the developed world throughout the great moderation. The ability of the median wage in the developing world to buy oil or copper or anything else evaporated. We got it all.

Saying we need to relieve capital from taxation in order to avoid a 1970s type scenario perhaps is acknowledging that we need to increase inequality in our country as a way to drive greater inequality between the rich countries and poor countries. Personally I’d rather we made a good go at enabling commodities to be spread further through measures such as efficiency, recycling, renewables etc.

March 20th, 2013 at 3:53 am PDT

link

stone @30

“With an asset tax real estate would have to have the tax paid on it in order for the owner to demonstrate ownership (just as with car tax in the UK now).”

So you are now a (Henry) Georgian? He also argued it would force the assets to be used. With land I have less problem, because it is already valued and can be based on observed rents (averaged over a year). I’m less sure how it would work with financial assets, particular if they are rarely traded.

You do mention that the tax would go with the assets – and not be dependent on who owned them. I find this a bit disturbing. Aren’t we going to potentially really squeeze the retired middle class? Where would progressivity come from?

March 20th, 2013 at 6:04 am PDT

link

[…] upon which the Chamley-Judd results are built, as a sufficient description of the macroeconomy. [1] Some economists might argue that it’s a decent workhorse “asymptotically”, as a means of […]

March 20th, 2013 at 6:12 am PDT

link

[…] that the Chamley-Judd result is “not too fragile, it’s too solid”. As far as I can tell [2], the optimality of a zero capital tax rate is in fact a “knife-edge” result with respect to […]

March 20th, 2013 at 6:15 am PDT

link

[..] Fundamentally, Chamley-Judd logic suggests that we should tax least the factor most capable of expanding to engender economic growth. You don’t have to be a new-age nut to believe that human and institutional development, which yield return in the form of wages, may well be that factor. It is perfectly possible, under this logic, that the roles of capital and labor are reversed, that the optimal tax on labor should be zero or even negative […]

True if indeed one assumes all labor only gets rewarded through wages. This is arguably not the case for all labor. Labor that adds most to “human development” will generally see a lesser part of its “return in the form of a wages” and a larger part as capital gains. Lower capital taxes thus (already) lower the effective tax rate for the most productive labor.

March 20th, 2013 at 7:20 am PDT

link

TravisV @28

Maybe you should tone down your language a bit.

“Sure human knowledge in totality can grow but as I mentioned before, savings is the only possible vehicle for transforming that knowledge into tangible results.”

Clearly not true. Economists have been trying to numerate what drives productivity growth for just about ever, and there is always a residual that can’t just be explained by embodied capital.

I’m also not sure what you exactly mean by savings – it seems clearer to me to call it physical capital – why is that a strange name. Financial savings is only an intermediary – ultimately it is the diversion of real resources into real investment that counts.

March 20th, 2013 at 7:26 am PDT

link

TravisV @28

“that increasing savings (physical capital as Waldman strangely calls it) are the only way to implement technological changes”

This is also not clear, given that all capital stock wears out and has to be replaced, why is INCREASED savings obviously necessary?

March 20th, 2013 at 7:30 am PDT

link

reason@39, “You do mention that the tax would go with the assets – and not be dependent on who owned them. I find this a bit disturbing. Aren’t we going to potentially really squeeze the retired middle class? Where would progressivity come from?”

Asset ownership is much more unequal across the population than is income. That makes it dramatically progressive without discriminating between people. Think of Warren Buffet with $40B. You wouldn’t need much of a % of that to relieve him of his anxiety about not paying enough tax.

If all other taxes were replaced by an asset tax then we would have more left to save during our working lives because it would not be going to other taxes. The key thing is that overall the government would not be taking any more out of the economy. If you were earning a median wage throughout your life you would have paid less into taxes. I agree that in the transition, the current crop of middle class retirees would not benefit. As it stands however they have been dramatically messed up by our current bubble and bust asset markets and so many anyway have to rely on state pensions. If necessary, increase state pensions. In general I think it gives much more bang for the buck to bail out the elderly directly rather than attempting to via Wall street.

March 20th, 2013 at 10:54 am PDT

link

Chamley’s paper says that he assumes everyone has the same discount rate because otherwise the solution is not stable. Since we know that discount rates differ, if we allowed for different discount rates in Chamley’s model all financial wealth would eventually accrue to those with the lowest discount rates – hmmmm.

March 20th, 2013 at 12:50 pm PDT

link

stone @45

But that means the tax has to be high enough to make it hard it build big asset piles, but not high enough to discourage investment. I don’t see this tightwalk rope as being easy. With an estate tax (without loopholes) every now and then assets might have to be sold to pay the tax – I think this is a good thing by the way – but with a wealth tax this wouldn’t normally be true. So it doesn’t get any harder to go from a big pile of assets to a massive pile of assets. I think it should. That is what happens in nature, where the effort involved in defending a territory increases faster than the area of the territory. Assets don’t disappear if they change owners, you need to get assets sold to pay taxes to spread them out.

“The key thing is that overall the government would not be taking any more out of the economy.”

I think this is a misunderstanding. Tax is not what the government takes from the economy, it is the real resources that the government uses that count. The government usually gives roughly as much (often more) money than it takes.

March 21st, 2013 at 4:37 am PDT

link

Joe Smith @46

Yes, you will usually find that the behaviour of models is driven more by the assumptions than by the parameters. If the behaviour you are interested in is governed by the assumptions, then the model is completely useless, as your argument is a tautology.

March 21st, 2013 at 4:46 am PDT

link

Joe Smith @46

Then make the discount rate a decreasing function of wealth.-)

March 21st, 2013 at 4:50 am PDT

link

Stone,

don’t get me wrong here, I’m not trying to put you off, as I said up front it is an idea that I in principle like, I just don’t think it flies in practice, and I’m trying to get you to think harder about it.

March 21st, 2013 at 5:00 am PDT

link

Joe Smith,

one thing that I think really matters here, is that economics assumes that people get all their utility from consumption. But I think people get some utility from wealth (or at least from the a. security b. power that comes with it). It would be very useful to incorporate that into standard economics.

March 21st, 2013 at 5:03 am PDT

link

reason @50, I’ve had a go trying to work out as much as I could about whether an asset tax could get us out of the hole we are in. I’ve put it in the pdf http://directeconomicdemocracy.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/direct-economic-democracy8.pdf

You say it should be hard to go from a big pile of assets to a massive pile of assets. I’m totally pragmatic about it. If someone is absolutely great at commanding a large empire of assets, then great; it is good for us all that someone is able to get everything put to good use. In practice it gets very hard to do things on a huge scale. That is why an asset tax is needed. The current system means that compounding return on capital causes wealth to be concentrated as fast as the inefficiencies of bloated scale cause uncompetitiveness.

Remember everyone working is getting a wage. That is a fixed input to potential savings. I’m also in favor of a citizens dividend. That is another fixed input. Under an asset tax, most people would pretty much just maintain the value of what they save. You would have to be doing something special to amass a fortune. Now a fortune will amass itself just by passive return on capital.

March 21st, 2013 at 10:52 am PDT

link

I had some comments but they turned out to be too long for a comment. So I wrote them up in a blog post here: http://hyperplanes.blogspot.com/2013/03/waldman-on-capital-gains-taxes.html

March 21st, 2013 at 3:06 pm PDT

link

I think you neglected to mention the key huge error in the Jones post on which he commented “the optimal tax rate on capital is zero.” The word “is” makes the claim totally incorrect. The Chamley Judd result states that as time goes to infinity the optimal tax rate on capital goes to zero. In plain American English, the correct version is “the optimal tax rate on capital will be zero.” (in the Queen’s English it is “the optimal tax rate on capital shall be zero”).

In particular consider the case of an Ramsey model with rich capital owners, poor workers and an egalitarian government. The Chamley Judd result is that a government which can only tax capital (and can’t redistribute lump sum or tax consumption) and which can’t precommit will cease to redistribute when perfect equality is achieved.

The result, basically, is that if everyone is perfectly equal, then an egalitarian won’t change things.

In contrast, with precommitment and with empirical plausible parameter values, the optimal policy is to redistribute more so that those who were rich end up poorer than those who were poor.

Here are proofs of these claims (warning PDF heroically constructed by Sigve Indregard) http://tinyurl.com/2vwkl8k

None of this is a critique of Chamley Or Judd. It is just an explanation of what there result is. They made no claim about optimal policy in 2013 or 3013 or 10000000 AD. They only discussed what would happen to optimal policy as time goes to infinity,

Chamley-Judd should be ” more central to economic discussion?”, Why isn’t it “part of the canon that all economists breathe in” and “?in our freshman textbooks” “taught to everyone” when time has gone to infinity, that is never.

Jones left a little something out, but that little something wasn’t finite.

March 22nd, 2013 at 7:47 am PDT

link

´How and whether an incremental purchase of financial claims contributes to growth or helps workers is a complicated question, one that a Ramsey model can’t resolve.´

This should be common sense.

Isn´t there a basic story also about the evolution of the economy in terms of the porportionate goods/services mix?

(I haven´t looked at the numbers, but I assume there is such a story.)

I.e., the economy has gotten progressively, proportionately ´lighter´ in terms of physical capital,over time?

If so, human capitalization should have become progressively, proportionately heavier than physical capitalization, over time.

And does this correlate (perhaps causally) with increased financial complexity and layering, over time?

March 22nd, 2013 at 8:51 am PDT

link

What Robert Said. You’re much too generous to Chamley, who set boundaries rather strictly and redundantly. (I read the paper as “Gee, current US accounting practices are correct,” since all it said was that, if you reach the point where all you’re doing with capital is replacing it [CapX=depreciation, as it were], you shouldn’t tax replacing it. That it gets cited as evidence that you shouldn’t tax capital at all seems to be either because economists cannot read or cannot think through the implications of their own models.)

The corollary to the condition under which you shouldn’t tax capital, as Robert notes, is that you need to be taxing income (all types) at almost 100%. (Only one worker, and all she does is push a button so that the machines do all the work.) Strangely, that aspect tends to be ignored by those who preach the glories of Chamley’s “proof.”

March 22nd, 2013 at 9:34 am PDT

link

JKH@55, “the economy has gotten progressively, proportionately ´lighter´ in terms of physical capital,over time”

There was a fascinating BBC radio program about Moore’s law where a big deal was made of the fact that silicon chip factories were becoming ever more vastly expensive to build. Now millions of chips have to be made before break even point. The factories have robots doing the labour and those robots are built by robots. Isn’t that a heavier a use of physical capital than the old skool way of having people at the production line?

Perhaps when robots are doing all of the real work that creates a surplus that can in effect be “taxed” by financialization. Perhaps the financialization is not conducive for the real economy any more than say fighting foreign wars is. It is simply that the more advanced economy can carry a higher parasitic burden ????

Lets not forget too that many manufacturing jobs have been off-shored.

March 22nd, 2013 at 9:37 am PDT

link

stone,I would say that both physical capital and non-physical capital have increased enormously in tech manufacturing. The training required to work a fab to make chips is huge. Robots are required for things because so much of the actual work must be done in pristine environments although the processes are not automated. Also, the capital is expensive and lithography is the primary input, but the major cost of running a fab is the commodity price of silicone wafers.

March 22nd, 2013 at 6:09 pm PDT

link

Jeremy Grantham wrote something interesting about what JKH@55 was describing. He does also say the same as Error@58 that the current manufacturing jobs are highly skilled and paid but adds that they are vanishing too:

http://www.gmo.com/websitecontent/JG_LetterALL_11-12.pdf

“…there is no more productivity per man-hour at all, but only productivity per robot-hour or per unit of capital employed. This deepening of capital and technology almost guarantees that productivity will continue to be high in manufacturing even as the percentage of the total workforce employed there dwindles away toward zero. As the rest of us do each other’s art appraisals and investment management we can fantasize about productivity, but it will mainly represent hard to measure qualitative improvements. (On a hypothetical island where services are outlawed and only manufacturing exists, the final position is that automation, and thereby capital, produces everything while all of the mere mortals sit on the beach. And starve? The worthless unemployed who are obviously not carrying their weight? Ah, there’s the rub! Up the beach, in a protected, cordoned-off section is the capital owners’ club. There, a handful of equally “unemployed” owners sit, enjoying tea and the ocean.”

March 23rd, 2013 at 5:01 am PDT

link

”

get the yield to pay the tax with.

”

~~Stone~

Perhaps, but in our shoot-from-the-hip-rush to tax the obvious, tax the concrete, tax the traditional have we overlooked the-opportunity-cost of taxing the capital at the expense of not taxing the abstract?

When you deposit your paycheck into a deposit account the abstract value of your deposit-transaction is your negative-crowding-out. When government/gals/guys delay spending allocated funds they simultaneously create the negative-crowding-out-bit-coin. Do you see what is happening?

We are taxing the concrete when we should be taxing the crowding-out. Ah! But there are two subsets of positive-crowding-out. There is the crowding-out of productive processes, supplies, labour, and energy. By contrast, there is the opposite subset of non-productive-Veblen-goods. The latter subset should be taxed but not the former. Careful now! This is an abstraction.

Sort it out

!

March 24th, 2013 at 1:11 am PDT

link

Global Groundhog@60, my point is that “abstract” financial assets as you call them reveal that they are pretend and not contributing to the productive economy by the very fact that they fail to sustain a sufficient yield to pay an asset tax with. A certain amount of “abstract” value storage may actually facilitate the function of the real economy. IMO the only way to know how much is enough is by having an asset tax such that those people who hold an appropriate blend of “abstract” and tangible productive assets are the people who end up with the most overall gains over and above paying the ongoing asset tax. Their way of doing things will then be what prevails.

March 24th, 2013 at 2:43 am PDT

link

”

blend of “abstract” and tangible productive assets are the people who end up with the most overall gains over and above paying the ongoing asset tax. Their way of doing things will then be what prevails.

”

merely the most adaptable blend will be allowed to continue its chosen path of evolution.

Got it

!

March 25th, 2013 at 12:21 am PDT

link

rich capital owners, poor workers and an egalitarian government

This is either an impossibility or a pre-revolutionary situation:-)

That said, another problem with the C-J argument is distinguishing income from labour and from capital – at the margin, this is a distinction driven by tax-evasion. In C-J world, it very much makes sense to reclassify yourself as self-employed, and therefore making profit rather than earning wages. And we know that it is possible to go quite a long way with this in a modern economy.

But I think it ought to be a condition of an economic model with normative claims that it should be robust to common tax-evasion strategies.

Further, it’s interesting that economists who think finance is merely a veil over real production also think real production is basically just like finance. Rather, they think it is like the easy bits of finance, for example, British government bonds – negligible transaction costs, huge liquidity, instant and frictionless trading, authoritative pricing and well-defined pricing models, abundant and public information.

March 26th, 2013 at 10:17 am PDT

link

Heavens should be simple…or to use quote from this article:

– Good economic policy doesn’t try to do things that are impossible…

Is this is what my peers are debating…five years into a crises that leg 99% of us behind…are we really still debating tax rate on capital? And “zero” no less?

To accomplish what? Employment? Growth?

Then again, I have to pinch my self and remind that I am not into Twilight zone of economics…no…its just the usual bonafide attempt to give Capitalism reason behind his flaws…

Why are we still debating tax rate, that shouldn’t be the question we should focus on…why we forget the simple truth…taxes are price to run civilized society and price no business owner are willing to pay if he can avoid them…

To even enter in calculations of their rate is matter of discussing what theologians use to do answering: how many angels are dancing on the top of a needle…

Its not exotic adventure…its fruitless…

It imply we forget that the Capital goals is to be thrown back into circulations cause its driven by the Laws similar to gravity in physics, and no tax burden will diminish those Laws…to dispute them is matter of academics, its not practical adventure…

We can indulge in pursuit of mathematically formulated Eldorado, but that will be just as poetic if not useless…

None will solve unemployment…cause unemployment is not some shock that hit investors coming out of the blue, its the DNA of Capitalism …

Deal with it…slowly…

Its the wages…always the wages…

And that blow all the little models out of equation…

I can not spend more then I am paid for…How simple is that?

If I don’t spend, you will not sale…

If you don’t sale you will make no profit…

Without profit the business cycle is nothing but dead…

Forget about taxes, econometrics models, theories and fancy names…

No matter how much money one have in the bank, no matter how advantage his investments are…if one dont sale, if one don’t make profit, the business cycle is nothing but dead…

Here comes the perpetuum mobile of modern economics…credits…

Credits and debt…and who will pay for them…

Government…who are we kidding…taxes again?

Workers? to assume that if we don’t charge capital any taxes that he will transfer the gain into wages is not a joke…its absurd…

The vicious cycle of apologies start again…

The reason why the central banks enter the scene…the old buccaneers…

“To the degree that human and institutional capital grow with use rather than disuse, shifting the burden of taxation from financial claims to labor may be harmful over a very long-term. In the asymptotic steady state, who knows?”

The answer is History…

March 26th, 2013 at 1:28 pm PDT

link

[…] a quick hit, in comments at Steve Randy Waldman’s: Economists who think finance is merely a veil over real production also think real production is […]

March 26th, 2013 at 7:23 pm PDT

link

Marie@64 You say that a profit can’t be made if customers don’t have enough wages to spend. The problem is that paying greater wages results in having less profits in the first place. Isn’t it true that it is spending of profits that is the critical thing for ensuring subsequent profits? So I think ensuring that ownership of the stream of profits needs to be with those with a greater propensity to spend. In the UK we have a retailer company called the John Lewis Partnership. It is employee owned and all the profits go to all of the staff. Isn’t that the way to ensure customers can afford to provide enough custom to ensure profits can be made?

March 27th, 2013 at 3:55 am PDT

link

@stone….

True…what I’m saying is that the vicious cycle will continue no matter if we accommodate business giving them a tax break or not…

I don’t know about UK, but it’s public secret in America that our Corporate effective taxes are low, so low that are already zero for many corporations…

To debate taxes in crises as way to reboot the business cycle is actualy debating effect on public debt & transferring the cost on taxpayers back, same taxpayers who are workers in the other side of the isle and who already have diminished purchasing power…

Diminishing taxes will blow the revenue the Govt collect, it will not change the trajectory of the system, cause business pay no taxes, it pass them to costomers anyway…

Why then when taxes are raised investments are spurred, as in the 90, during Clinton???

Cause the increased cost of business just turn future investment look profitable enough to undertake risk…

The diminishing return don’t look diminishing anymore….

Your model is better…and America slowly catching up with it, I have one “workers own enterprise in my naighborhood…also retailer…

http://twitpic.com/bhxmer

Marie

March 27th, 2013 at 10:38 am PDT

link

”

yields on debt, risk-free, corporate, and individual, have been falling since the 1980s, while the stock of financial assets held by households (as a share of GDP) has grown inexorably.

”

Depends on ones perspective! Depends which side of the tracks you have made your home. Perhaps during the 70-s t-bonds were paying more each year of double digit, but credit card interest was small. Now you get tiny interest on your t-bond but keep rolling them over just to have reserve funds that will help you avoid borrowing on your credit-card. With credit-card-interest-penalties-fees-and-other-interest-disguised-as-other-things so sky high, the fear of not postponing expenditures is what keeps the lazy cash in deposit accounts and t-bills, not the lure of interest on the bills. Interest rates are truly a gamut of things to a variety of people at various stages of their lives. Factor in the interest paid by the poor who pay a fee to cash their paychecks then your *epoch of the low rates* doesn’t seem so low after all.

But where does it go, the interest paid by poor? Not to bank shareholders. Ah! To banker bonuses, thence to their lobbyists, through re-election committees, to the special interests, but with the pot pinched by mobsters at every turn.

Share holders don’t get much, but their servants are paying exquisite-ly high interest on the money borrowed to buy the lotto ticket. When will servants realize that empty hope is free for the asking? That they don’t need no stinking ticket to prove that they have the empty hope?

March 28th, 2013 at 1:07 am PDT

link

the economy has gotten progressively, proportionately ´lighter´ in terms of physical capital,over time?

I don’t think this is true.

There are basically two patterns. During industrialization, there is a broad increase of capital intensity, combined with a shift of expenditure toward capital-intesive sectors. (Rich people hire fewer servants, buy more luxury goods — Adam Smith describes this vividly.) In advanced economies, individual sectors continue to become more capital-intensive, but the mix of consumption shifts toward more labor-intensive sectors, so the overall capital-labor mix remains roughly constant. That’s been the pattern in the US since WWII at least.

It may be that in the future we’ll see a shift away from embodied capital. But that has not happened yet.

March 28th, 2013 at 6:19 pm PDT

link

[…] He expresses befuddlement at Steve Randy Waldman’s typically brilliant post, K is not capital, L is not labor. […]

March 29th, 2013 at 10:15 am PDT

link