Scale, progressivity, and socioeconomic cohesion

Today seems to be the day to talk about whether those of us concerned with poverty and inequality should focus on progressive taxation. Edward D. Kleinbard in the New York Times and Cathie Jo Martin and Alexander Hertel-Fernandez at Vox argue that focusing on progressivity can be counterproductive. Jared Bernstein, Matt Bruenig, and Mike Konczal offer responses offer responses that examine what “progressivity” really means and offer support for taxing the rich more heavily than the poor. This is an intramural fight. All of these writers presume a shared goal of reducing inequality and increasing socioeconomic cohesion. Me too.

I don’t think we should be very categorical about the question of tax progressivity. We should recognize that, as a political matter, there may be tradeoffs between the scale of benefits and progressivity of the taxation that helps support them. We should be willing to trade some progressivity for a larger scale. Reducing inequality requires a large transfers footprint more than it requires steeply increasing tax rates. But, ceteris paribus, increasing tax rates do help. Also, high marginal tax rates may have indirect effects, especially on corporate behavior, that are socially valuable. We should be willing sometimes to trade tax progressivity for scale. But we should drive a hard bargain.

First, let’s define some terms. As Konczal emphasizes, tax progressivity and the share of taxes paid by rich and poor are very different things. Here’s Lane Kenworthy, defining (italics added):

When those with high incomes pay a larger share of their income in taxes than those with low incomes, we call the tax system “progressive.” When the rich and poor pay a similar share of their incomes, the tax system is termed “proportional.” When the poor pay a larger share than the rich, the tax system is “regressive.”

It’s important to note that even with a very regressive tax system, the share of taxes paid by the rich will nearly always be much more than the share paid by the poor. Suppose we have a two animal economy. Piggy Poor earns only 10 corn kernels while Rooster Rich earns 1000. There is a graduated income tax that taxes 80% of the first 10 kernels and 20% of amounts above 10. Piggy Poor will pay 8 kernels of tax. Rooster Rick will pay (80% × 10) + (20% × 990) = 8 + 198 = 206 kernels. Piggy Poor pays 8/10 = 80% of his income, while Rooster Rich pays 206/1000 = 20.6% of his. This is an extremely regressive tax system! But of the total tax paid (214 kernels), Rooster Rich will have paid 206/214 = 96%, while Piggy Poor will have paid only 4%. That difference in the share of taxes paid reflects not the progressivity of the tax system, but the fact that Rooster Rich’s share of income is 1000/1010 = 99%! Typically, concentration in the share of total taxes paid is much more reflective of the inequality of the income distribution than it is of the progressivity or regressivity of the tax system. Claims that the concentration of the tax take amount to “progressive taxation” should be met with lamentations about the declining quality of propaganda in this country.

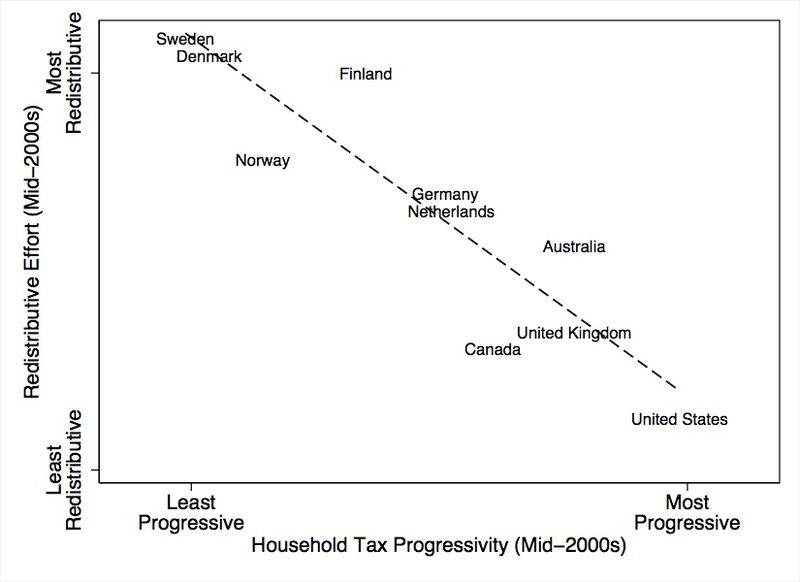

Martin and Hertel-Fernandez offer the following striking graph:

The OECD data that Konczal cites as the likely source of Martin and Hertel-Fernandez’s claims includes measures of both tax concentration and progressivity. I think Konczal has Martin and Hertel-Fernandez’s number. If the researchers do use a measure of tax share on the axis they have labeled “Household Tax Progressivity”, that’s not so great, particularly since the same source includes two measures intended to capture of actual tax progressivity (Table 4.5, Column A3 and B3). Even if the “right” measure were used, there are devils in details. These are “household taxes” based on an “OECD income distribution questionnaire”. Do they take into account payroll taxes or sales taxes, or only income taxes? This OECD data shows the US tax system to be strongly progressive, but when all sources of tax are measured, Kenworthy finds that the US tax system is in fact roughly proportional. (ht Bruenig) The inverse correlation between tax progressivity and effective, inclusive welfare states is probably weaker than Martin and Hertel-Fernandez suggest with their misspecified graph. If they are capturing anything at all, it is something akin to Ezra Klein’s “doom loop”, that countries very unequal in market income — which almost mechanically become countries with very concentrated tax shares — have welfare states that are unusually poor at mitigating that inequality via taxes and transfers.

Although I think Martin and Hertel-Fernandez are overstating their case, I don’t think they are entirely wrong. US taxation may not be as progressive as it appears because of sales and payroll taxes, but European social democracies have payroll taxes too, and very large, probably regressive VATs. Martin and Hertel-Fernandez are trying to persuade us of the “paradox of redistribution”, which we’ve seen before. Universal taxation for universal benefits seems to work a lot better at building cohesive societies than taxes targeted at the rich that finance transfers to the poor, because universality engenders political support and therefore scale. And it is scale that matters most of all. Neither taxes nor benefits actually need to be progressive.

Let’s try a thought experiment. Imagine a program with regressive payouts. It pays low earners a poverty-line income, top earners 100 times the poverty line, and everyone else something in between, all financed with a 100% flat income tax. Despite the extreme regressivity of this program’s payouts and the nonprogressivity of its funding, this program would reduce inequality in America. After taxes and transfers, no one would have a below poverty income, and no one would earn more than a couple of million dollars a year. Scale down this program by half — take a flat tax of 50% of income, distribute the proceeds in the same relative proportions — and the program would still reduce inequality, but by somewhat less. The after-transfer income distribution would be an average of the very unequal market distribution and the less unequal payout distribution, yielding something less unequal than the market distribution alone. Even if the financing of this program were moderately regressive, it would still reduce overall inequality.

How can a regressively financed program making regressive payouts reduce inequality? Easily, because no (overt) public sector program would ever offer net payouts as phenomenally, ridiculously concentrated as so-called “market income”. For a real-world example, consider Social Security. It is regressively financed: thanks to the cap on Social Security income, very high income people pay a smaller fraction of their wages into the program than modest and moderate earners. Payouts tend to covary with income: People getting the maximum social security payout typically have other sources of income and wealth (dividends and interest on savings), while people getting minimal payments often lack any supplemental income at all. Despite all this, Social Security helps to reduce inequality and poverty in America.

Eagle-eyed readers may complain that after making so big a deal of getting the definition of “tax progressivity” right, I’ve used “payout progressivity” informally and inconsistently with the first definition. True, true, bad me! I insisted on measuring tax progressivity based on pay-ins as a fraction of income, while I’m call pay-outs “regressive” if they increase with the payees income, irrespective of how large they are as a percentage of payee income. If we adopt a consistent definition, then many programs have payouts that are nearly infinitely progressive. When other income is zero, how large a percentage of other income is a small social security check? Sometimes, to avoid these issues, the colorful terms “Robin Hood” and “Matthew” are used. “Robin Hood” programs give more to the poor than the rich, “Matthew” programs are named for Matthew Effect — “For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken even that which he hath.” Programs that give the same amount to everyone, like a UBI, are described less colorfully as “Beveridge”, after the recommendations of the Beveridge Report. The “paradox of redistribution” is that welfare states with a lot of Matthew-y programs, that pay more to the rich and may not be so progressively financed, tend to garner political support from the affluent “middle class” as well as the working class, and are able scale to an effective size. Robin-Hood-y programs, on the other hand, tend to stay small, because they pit the poor against both the moderately affluent and the truly rich, which is a hard coalition to beat.

So, should progressives give up on progressivity and support modifying programs to emulate stronger welfare states with less progressive finance and more Matthew-y, income-covarying payouts? Of course not. That would be cargo-cultish and dumb. The correlation between lower progressivity and effective welfare states is the product of an independent third cause, scale. In developed countries, the primary determinant of socioeconomic cohesiveness (reduced inequality and poverty) is the size of the transfer state, full stop. Progressives should push for a large transfer state, and concede progressivity — either in finance or in payouts — only in exchange for greater scale. Conceding progressivity without an increase in scale is just losing. As “top inequality” increases, the political need to trade away progressivity in order to achieve program scale diminishes, because the objective circumstances of the rich and erstwhile middle class diverge.

Does this focus on scale mean progressives must be for “big government”? Not at all. Matt Bruenig has written this best. The size of the transfer state is not the size of the government. When the government arranges cash transfers, it recruits no real resources into projects wasteful or valuable. It builds nothing and squanders nothing. It has no direct economic cost at all (besides a de minimis cost of administration). Cash transfer programs may have indirect costs. The taxes that finance them may alter behavior counterproductively and so cause “deadweight losses”. But the programs also have indirect benefits, in utilitarian, communitarian, and macroeconomic terms. That, after all, is why we do them. Regardless, they do not “crowd out” use of any real economic resources.

Controversies surrounding the scope of government should be distinguished from discussions of the scale of the transfer state. A large transfer state can be consistent with “big government”, where the state provides a wide array of benefits “in-kind”, organizing and mobilizing real resources into the production of those benefits. A large transfer state can be consistent with “small government”, a libertarian’s “night watchman state” augmented by a lot of taxing and check-writing. As recent UBI squabbling reminds us, there is a great deal of disagreement on the contemporary left over what the scope of central government should be, what should be directly produced and provided by the state, what should be devolved to individuals and markets and perhaps local governments. But wherever on that spectrum you stand, if you want a more cohesive society, you should be interested in increasing the scale at which the government acts, whether it directly spends or just sends.

It may sometimes be worth sacrificing progressivity for greater scale. But not easily, and perhaps not permanently. High marginal tax rates at the very top are a good thing for reasons unrelated to any revenue they might raise or programs they might finance. During the postwar period when the US had very high marginal tax rates, American corporations were doing very well, but they behaved quite differently than they do today. The fact that wealthy shareholders and managers had little reason to disgorge the cash to themselves, since it would only be taxed away, arguably encouraged a speculative, long-term perspective by managers and let retained earnings accumulate where other stakeholders might claim it. In modern, orthodox finance, we’d describe all of this behavior as “agency costs”. Empire-building, “skunk-works” projects with no clear ROI, concessions to unions from the firm’s flush coffers, all of these are things mid-20th Century firms did that from a late 20th Century perspective “destroyed shareholder value”. But it’s unclear that these activities destroyed social value. We are better off, not worse off, that AT&T’s monopoly rents were not “returned to shareholders” via buybacks and were instead spent on Bell Labs. The high wages of unionized factory workers supported a thriving middle class economy. But would the concessions to unions that enabled those wages have happened if the alternative of bosses paying out funds to themselves had not been made unattractive by high tax rates? If consumption arms races among the wealthy had not been nipped in the bud by levels of taxation that amounted to an income ceiling? Matt Bruenig points out that, in fact, socioeconomically cohesive countries like Sweden do have pretty high top marginal tax rates, despite the fact that the rich pay a relatively small share of the total tax take. Perhaps that is the equilibrium to aspire to, a world with a lot of tax progressivity that is not politically contentious because so few people pay the top rates. Perhaps it would be best if the people who have risen to the “commanding heights” of the economy, in the private or the public sector, have little incentive to maximize their own (pre-tax) incomes, and so devote the resources they control to other things. In theory, this should be a terrible idea: Without the discipline of the market surely resources would be wasted! But in the real world, I’m not sure history bears out that theory.

Update History:

- 12-Oct-2014, 7:10 p.m. PDT: “When the

governmentsgovernment arranges cash transfers…” - 21-Aug-2020, 3:0e p.m. EDT: Robin-Hood-y programs, on the other hand, tend to stay…

“Regardless, they do not “crowd out” use of any real economic resources.”

Provably false.

Line up every single human on one side of a tug of war rope, and tell them to pull.

Now tell old women and children they don’t have to pull.

Now tell someone else they don’t have to.

The TOTAL PULL = side of pie to consume.

Every person not pulling is less pie. Period. The end.

There may be good reasons for giving people breaks from pulling, but if you SAY you are most concerned with consumption levels for the poor… AND THIS IS WHAT RAWLS SAYS…

Then you do not grants people who have the ability to pool, to decide to never pull.

YOU CAN SAY OUT LOUD: “I do not care if the poor as a whole get to consume less amongst themselves, it matters more to me they do not have to work”

But have the strength to admit it to all of us.

October 11th, 2014 at 7:10 am PDT

link

“The fact that wealthy shareholders and managers had little reason to disgorge the cash to themselves, since it would only be taxed away, arguably encouraged a speculative, long-term perspective by managers and let retained earnings accumulate where other stakeholders might claim it.”

This appears to me to be what Yglesias is getting at here:

http://www.vox.com/2014/10/7/6921153/buybacks-dividends?utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter&utm_campaign=mattyglesias&utm_content=tuesday

“But these four sentences by Lu Wang and Callie Bost at Bloomberg tell us an enormous amount about where the economy is today. They start with the observation that big companies are poised to spend about 95 percent of their profits this year on dividends and share buybacks. And there’s a larger trend:

“CEOs have increased the proportion of cash flow allocated to stock buybacks to more than 30 percent, almost double where it was in 2002, data from Barclays show. During the same period, the portion used for capital spending has fallen to about 40 percent from more than 50 percent. The reluctance to raise capital investment has left companies with the oldest plants and equipment in almost 60 years. The average age of fixed assets reached 22 years in 2013, the highest level since 1956, according to annual data compiled by the Commerce Department.”

What does this mean? It means that the basic link between healthy corporate profits and a healthy middle class is broken.”

October 11th, 2014 at 7:23 am PDT

link

Peter K.

Stock Buybacks occur when:

The regulatory environment ensures advantages flow to incumbents over newcos.

Large firms find themselves with comparative advantage NOT FROM vertical integration and buying power, but from a regulatory system with unmeasured negative externalities (big govt.)

SO they have LARGE profits.

But see little areas to invest at profit, so stock buybacks it is!

However, if we drop piranha in the water and favor newcos with little regulation and interference, the fat cattle will have to INVEST the profits they have to keep their market share.

it’s that simple.

Note: I’m not speaking about banks and traders. I’m talking about real stuff like:

1. Letting SMB owners move money freely tax free between investments.

2. Taxiing ALL personal consumption inside large firms as income: Business Class, Hotels nicer than Holiday Inn, anything above $40 a day in food.

3. And most important, if you decide you want to have a welfare system, don’t be an idiot and support a Minimum Wage – instead let minority SMB owners buy labor at a subsidized discount and go hunt and kill the fat cattle.

October 11th, 2014 at 8:03 am PDT

link

One’s ability to use their time effectively in the marketplace, is central to all this.

http://monetaryequivalence.blogspot.com/2014/10/how-does-inequality-matter.html

October 11th, 2014 at 8:38 am PDT

link

[…] 11:46 on October 11, 2014 by Mark Thoma Steve Waldman has a nice discussion of a recent debate: Scale, progressivity, and socioeconomic cohesion, Interfluidity: Today seems to be the day to talk about whether those of us concerned with poverty and inequality […]

October 11th, 2014 at 8:47 am PDT

link

Payout ratios in the 60’s were about the same as in the 90’s and payout ratios now are about where they have been at other times – maybe a little lower.

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2014/10/evidence-is-optional-for-finance-cynics.html

It’s always odd to me to see people argue that Wall Street has a short term focus when just 15 years ago, there was a huge stock market boom and bust that was based on an entire sector of firms who had never earned a profit, who were not near earning profits, and many of which never earned a profit.

October 11th, 2014 at 1:07 pm PDT

link

The graph is also a measure of cultural diversity (i.e. less cultural diverse, the higher taxes and redistribution, the more culturally diverse, the lower taxes and redistribution). Which is what you would expect. It is both easier to get consensus on a high level of state activity the less culturally diverse your society is and easier to run a “big state” without major inefficiencies, social tensions, etc.

October 11th, 2014 at 1:57 pm PDT

link

[…] interfluidity » Scale, progressivity, and socioeconomic cohesion […]

October 11th, 2014 at 4:16 pm PDT

link

You are so correct in what you are saying. And this shift in thinking will happen much sooner than we realize. What is going to take time is the manufacturing of consent to make everyone buy in (be they left of centre or right of centre). I don’t think people fully realize the collective wealth of the state that exists, and that can be distributed in a manner that does achieve the desired goal.

Robert Skidelsky says it best:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GgOhGexi1CY&list=PL6ED0A82B20435C39&index=55

Another video I recommend:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lLWgtAs5QH8&list=PL6ED0A82B20435C39&index=1

October 11th, 2014 at 5:03 pm PDT

link

That wasn’t really true for owners, although it might have been true for managers. For stocks and partnership shares held for less than a year, that’s true – but beyond that they were subject to capital gains tax, which was much less than the regular income tax brackets even in the 1950s. And of course, business owners had a lot more ability to manipulate expenses and reporting of income in order to dodge taxation.

Managers receiving a salary and a bonus generally couldn’t do that, and pieces from that era suggest they really did live more modestly compared to their predecessors of 20 years before. Mostly what really high rates do is make it hard for people to get that rich, so you end up with a mostly flatter distribution but with some rich elites with their money invested heavily in tax-favorable bonds and assets who never turn over or get replaced (Sweden has this issue, and the US had many of the Gilded Age wealthy families survive as wealthy throughout the Great Depression and Postwar Period).

October 11th, 2014 at 8:50 pm PDT

link

I think shifting taxation to being an asset tax would have a profoundly beneficial effect on the economy. But as you make clear, what is really important is that whatever taxation system we have has wide enough political support. http://directeconomicdemocracy.wordpress.com/2013/05/19/is-it-unjust-to-tax-assets/

October 12th, 2014 at 12:31 am PDT

link

[…] Scale, progressivity, and socioeconomic cohesion Steve Waldman […]

October 12th, 2014 at 3:56 am PDT

link

Steve: “It pays low earners a poverty-line income, top earners 100 times the poverty line, and everyone else something in between, all financed with a 100% flat income tax.”

You lost me at that point. That sentence seems self-contradictory to me. If low earners get (say) $10,000 after-tax income, and the (marginal?) tax rate is 100%, then everyone else must also get $10,000 after tax income.

October 12th, 2014 at 5:02 am PDT

link

OK, reading further, you seem to be making a distinction between taxes and transfer payments? To me there is no distinction. A transfer payment is just a negative tax. The only thing that matters (except, maybe, for administrative costs) is an individual’s *net* taxes, which is taxes minus transfer payments. The only thing that matters is the (schedule of) marginal *net* tax rates.

Is that what you are saying too?

October 12th, 2014 at 5:22 am PDT

link

Nick — Yes. I’m decomposing what you are calling net taxes (which may be negative) pretty conventionally, into first taxes on “pre-tax” or “market” income and then transfers.

In these examples, the marginal is the average and only tax rate. We start with a 100%, because it’s easy to do the math when the government takes all market income and replaces it with a transfer schedule (correlated with the market income it has taken). From there, it’s easy to see that a more plausible smaller program that simply scales the first down would still reduce inequality, as it would leave us with a weighted average of the fully taxed and original market distributions.

October 12th, 2014 at 7:17 am PDT

link

Steve, it’s time you retract;

“Regardless, they do not “crowd out” use of any real economic resources.”

There might be a better way to say whatever you meant, but this is simply wrong.

Anything that reduces PRODUCTION, reduces CONSUMPTION.

You need to say it in a way that PROVES transfer payment won’t reduce production.

That’s why GICYB rocks so much, it forces welfare recipients to produce (more to consume) AND forcing them, makes the guys picking up tab feel better about it – it keeps them happy to work all time.

October 12th, 2014 at 10:02 am PDT

link

Still need the retraction.

October 14th, 2014 at 1:54 am PDT

link

Morgan — There never will be a retraction. I’m not wrong. You are misunderstanding what it means to crowd out real economic resources.

Cash transfers may alter how people choose to use the productive resources at their disposal, but they do not alter the availability of productive resources. Human labor power exists. If the government directly burns oil, or if it employs people to do some pinko commie thing, there are simply fewer resources available for the private sector to work with, however people choose to use or not use those resources. That is not true of cash transfers.

Some transfer programs (say, a large income that is withdrawn if you get a job) would likely cause people to choose not to devote their labor power to formal market work. The resources haven’t been crowded out, they are there, but incentives have been created that redirect their use towards cottage production or leisure activities or mere disuse. Other transfer programs, say your own GICYB, might make transfers contingent upon accepting market work, and thus create incentives that cause people to devote more resources than they otherwise would to market labor. The transfer program I advocate most frequently, a UBI, creates countervailing effects. It raises workers reservation price to devote their labor power to market work. But simultaneously it increases demand for market work. The net effect should be to increase the price of labor with indeterminate effects on the quantity of labor power devoted to market work.

All of these programs, including your preferred policy, are potential transfer state activities. None of them diminish the resources available to the private sector as a whole. The choices made within the private sector about how to utilize those resources will undoubtedly be affected by incentives created by those programs, but the resources nevertheless are always there, in the possession of and available to the private sector for whatever uses private sector agents decide to put them to.

October 14th, 2014 at 4:00 am PDT

link

[…] Randy Waldman makes an interesting point also in response to the Vox article: what makes the difference to redistribution is not so much the […]

October 14th, 2014 at 8:11 am PDT

link

How would you determine the point at which it is worth trading off progressivity for scale? Is there a rule of thumb?

October 14th, 2014 at 8:48 am PDT

link

Steve, sorry wrong. Stop hiding behind abstract reasoning.

Human capital is hotel rooms or seats on airplane, if it isn’t used to produce TODAY, it’s gone.

WAKE UP.

TODAY, we can have two welfare recipients paint the room and fix the crib of a baby living with a single mom. TODAY, October 16th, 2014 she can be a better world, so that her Oct 19th, 2014 is brighter, cheerier, and slightly safer, so that she has that changing her .0001% into the next week, and her mom can be .1% happier, and NEXT week, two welfare recipients, can set traps to kill mice, and spray for bugs, so that by her Halloween 2014, her life has again shifted up.

If TODAY 30M welfare recipients do not get up and work for one another, 30M welfare recipients are WORSE OFF FOREVER compared to the alternative world where they do get up and work.

YOU, Steve, each day you waste, continuing to flap lips about your preferred whatever reduce the quality of life of the poor FOREVER.

Do you REALLY think this day, this week, this month, the year, that you spend publishing the same blah blah blah, is going to lay the groudn work for some magic new set up in 5 year, 10 years whatever, where the poor ARE BETTER OFF, than if TODAY they are put to work via a system that can pass – and they produce TODAY for one another?

Psst.. you (and the other similarly comfy abstract philosophers) aren’t that good at debate.

Stop bankng on your rhetorical skills, and think about what CAN PASS that TODAY can help that little girl and her mom.

Because it ain’t you holding out for your precious, it’s me crafting a software play that can be a lot of different welfare schemes and can PASS.

Steve, TODAY, the poor only get some % of the total production to consume.

And you are not being moral if you don’t admit that the average work product of the poor is more than likely consumed by other poor people.

Ay poor not working, is mostly less consumption for the poor.

Now PLEASE retract.

October 16th, 2014 at 5:05 am PDT

link

I’m sure you can do your work better next time.

October 19th, 2014 at 9:17 am PDT

link

[…] being/plainclothes-man-noticed-serving to-ebola-sufferer-shocks-nation”>serving to you scale again environmental affect. Energy productiveness – cheaply and reliably. select the Dell 22 […]

October 19th, 2014 at 6:59 pm PDT

link

Morgan,

it is not clear at all that what you are suggesting would increase supply (even in the short term, and almost certainly not in the medium term). Don’t forget the (real) resources you need to enforce your compulsion and handle exclusions. Don’t forget the possibility of people using the freedom from immediate necessity to invest in preparing for the future (perhaps in training, perhaps in experimenting with alternatives).

October 20th, 2014 at 8:11 am PDT

link

Morgan,

besides which as Steve pointed out, you clearly don’t understand what “crowding out” means. You are talking about another effect entirely (the possible lack of incentive effect).

October 20th, 2014 at 8:22 am PDT

link

reason, yeah I’m up on the lingo thanks!

“In economics, crowding out is argued by some economists to occur when increased government borrowing, a kind of expansionary fiscal policy, reduces investment spending.”

Note Steve said this:

“Regardless, they do not “crowd out” use of any real economic resources.”

Let me say this as plainly as possible, so you won’t flail at me again….

HUMAN LABOR is a real economic resource. It produces real things that other people want. MUCH OF IT produces today and it enjoyed for a day (food), a month (haircuts), years (rehabbed homes), or a lifetime, (daycare).

MOST OF WHAT POOR AND LOW SKILLED PEOPLE CONSUME is produced by other poor and low skilled people.

SO ANY effort to keep poor people from working TODAY (no work requirement) reduces the total pool of poor consumption.

And guess what? That consumption cannot be made up for by taking more from rich! It cannot be made up for IN THE FUTURE.

If TODAY a poor guy doesn’t paint the nursery for another poor person, there are COMPOUNDED negative effects each new day in future that room goes unpainted.

If TODAY, some poor mom doesn’t daycare for 4 other poor moms who go out to work, ALL THOSE KIDS are negatively affected again COMPOUNDED for each day the cheap daycare isn’t available.

Listen reason…

you seem smart enough to want to talk about the time and resources (I don’t use any more new resources, I just capture the labor for poor people) it takes to spin up GICYB…

And that’s MY POINT to steve.

TODAY, steve is harming poor people, by not being honest with himself and his readership about what is lost today, tomorrow, 2015, 2016, 2017 – and the MASSIVE piles of human misery that you all just wave away, so you can debate this subject without watching people suffer.

There are poor people right now MISERABLE, who are becoming RUINED for the rest of their life, by the status quo.

And my plan CAN PASS TODAY, you people talking endlessly about UBI – can even have your precious UBI in some state like Vermont, but that’s not good enough.

Instead, with NO END IN SIGHT to this debate where you pine away for UBI, NONE OF YOU have any idea WHEN your precious could even happen.

But no mind! Who cares!

Because and this is Rawls’ YOU DO NOT REALLY CARE ABOUT THE POOR.

You care about not having to work.

And that’s FINE, but stop talking about UBI like it is about ending poverty.

It is naive, disingenuous, and perhaps even nefarious.

Debates are real things, not academic discussions, IF there is a CRISIS in poverty…

We measure the level of crisis by how desperate the people screaming about it are to FIX IT NOW!

Desperate people compromise.

If you are desperate, you are not serious.

QED.

October 21st, 2014 at 9:16 am PDT

link

if you are not desperate you are not serious.

October 21st, 2014 at 9:17 am PDT

link

Morgan

You are dead wrong about poor people mostly consuming things produced by other poor people. If they are paying rent it is probably NOT to a poor person. If they are heating or cooling their house they are not depending on poor people to provide it. If they are sick they are not under the care of poor people. Most of the food they eat comes from megacorps and that can afford to undercut neighborhood grocers and if they eat at a restaurant its more than likely a McDonalds or its equivalent, definitely NOT a poor person. The forementioned things compose well over 90% of poor peoples budgets I would guess so I have no idea where you get your “fact”. Probably off Faux News……………. Drudge maybe.

October 24th, 2014 at 12:31 pm PDT

link